Every state manages its pension funds for state workers a little differently. States also vary in how much they make state workers pay for retirement benefits, too. As states begin to consider the financial impacts of COVID-19 on their budgets, here are some factors and trends to consider when assessing employee contribution rates:

In or Out of Social Security

Most of the 50 states enroll their state agency employees in a pension plan or a hybrid.[1] About 2/3rds of the states also enroll their state agency employees in Social Security. The states that do not participate in Social Security typically claim they offer larger retirement benefits to make up the difference.

COVID-19 Probably Means Increased Contributions

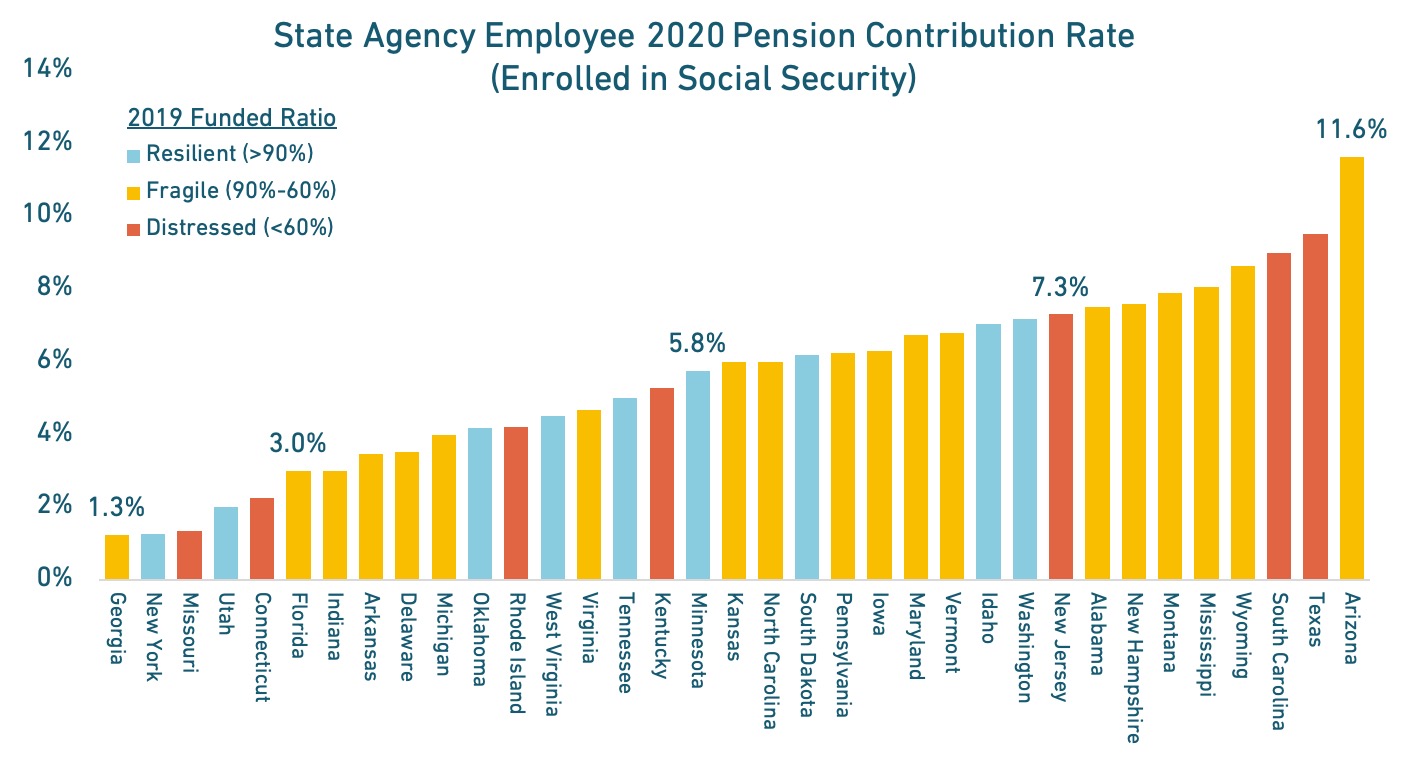

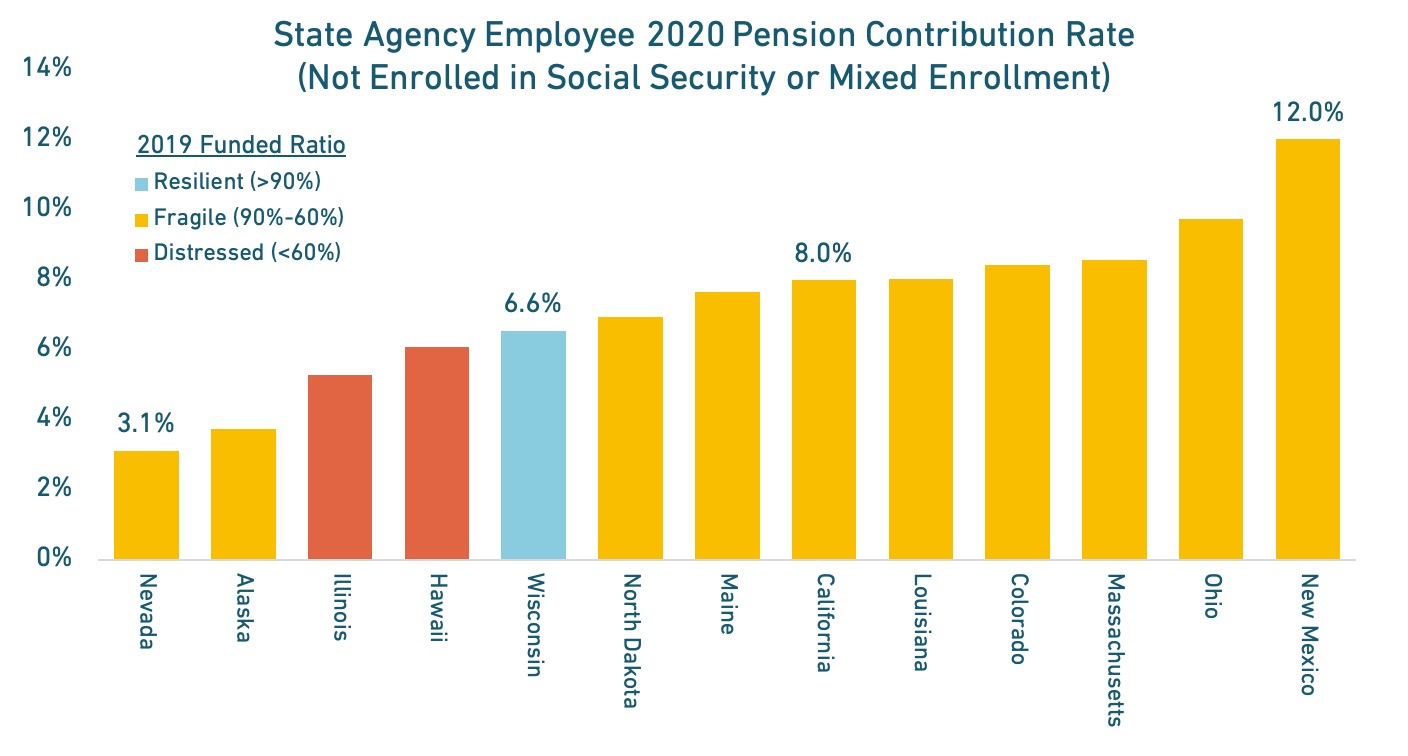

The amount that state agency employees contribute into pension funds for their own benefits varies considerably from state to state.[2] This is an important issue. Tax revenues are down across the country due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic turmoil. So there are likely going to be state legislatures that push to increase employee pension contributions in 2021, 2022, and 2023. After the Great Recession, many states turned their own employees for additional contributions to help offset increased pension costs. There is no reason to think the pattern won’t continue.

How Much Do State Workers Pay?

As states consider whether or not they have to do this again, here is a look at what contribution rate state agency employees are already paying into their pension funds. There are separate charts for states participating in Social Security, and those who do not.

Is this Reasonable?

In some cases it may be reasonable to ask employees to contribute more toward their own retirement. For example, employees in Social Security have to also contribute 6.2% of their salaries in taxes to the federal government. State workers out of Social Security do not have this money coming out of their checks, meaning they could in theory pay a bit more than what would otherwise be reasonable. But a key factor is whether salaries have been adjusted based on anticipated employee contributions.

Whether or not it is reasonable, increasing the money that pension plan members have to pay into their pension funds without increasing the benefits is effectively a pay cut, just by another name. With that in mind, any increase to employee contribution rates should only be undertaken with caution and in collaboration with affected stakeholder groups.

———-

Methodology Note & Footnotes

These charts show the employee contribution rate for the fiscal year ending 2020 (sometime between June 30 and December 31, depending on the state). The employee rates shown are for plans that cover state agency employees. In some states, these are stand alone plans that do not include public school or municipal employees (like Texas Employees’ Retirement System). In some states, these are plans that cover state and municipal workers together (like California Public Employees Retirement System). In other states, these are plans that cover all kinds of public workers including state agency employees (like Florida Retirement System). For pension plans where state agency employees have a specific contribution rate separate from other kinds of classified employees, we’ve shown the rate specific for state agency employees. For the purposes of this analysis, employees of the state legislature and governors office are considered state agency employees. Generally, public safety employees — even for the state — are considered as a separate classification from this analysis.

[1] Alaska, Michigan, and Oklahoma only offer new state agency employees defined contribution plans. Kansas and Kentucky only offer new state agency employees guaranteed return plans. In all four states, though, there are legacy employees who are still enrolled in a pension plan that will be slowly wound down over time.

[2] We are defining state agency employees as workers for state agencies/departments (e.g. Department of Transportation, Department of Education), the state legislature, the governors office, or any other non-municipal, non-school district, non-university employee. In most states, there are separate benefits and contribution rates for state public safety employees (like the State Police or employees in “hazardous” occupations).