Given the sophistication of finance in the 21st century, it is reasonable to think that America has a good understanding of how much in future pension benefits has been promised to teachers, librarians, school nurses, bus drivers, and other public school employees. But answering that question is a bit trickier than at first glance.

Equable Institute estimates that as of June 30, 2018 the shortfall for teacher pension funds managed by the 50 states and D.C. is $638.3 billion. Some of these teacher pensions are built into statewide retirement systems that cover more than teachers, so our estimate is based on removing the unfunded liabilities associated with non-public school employees.

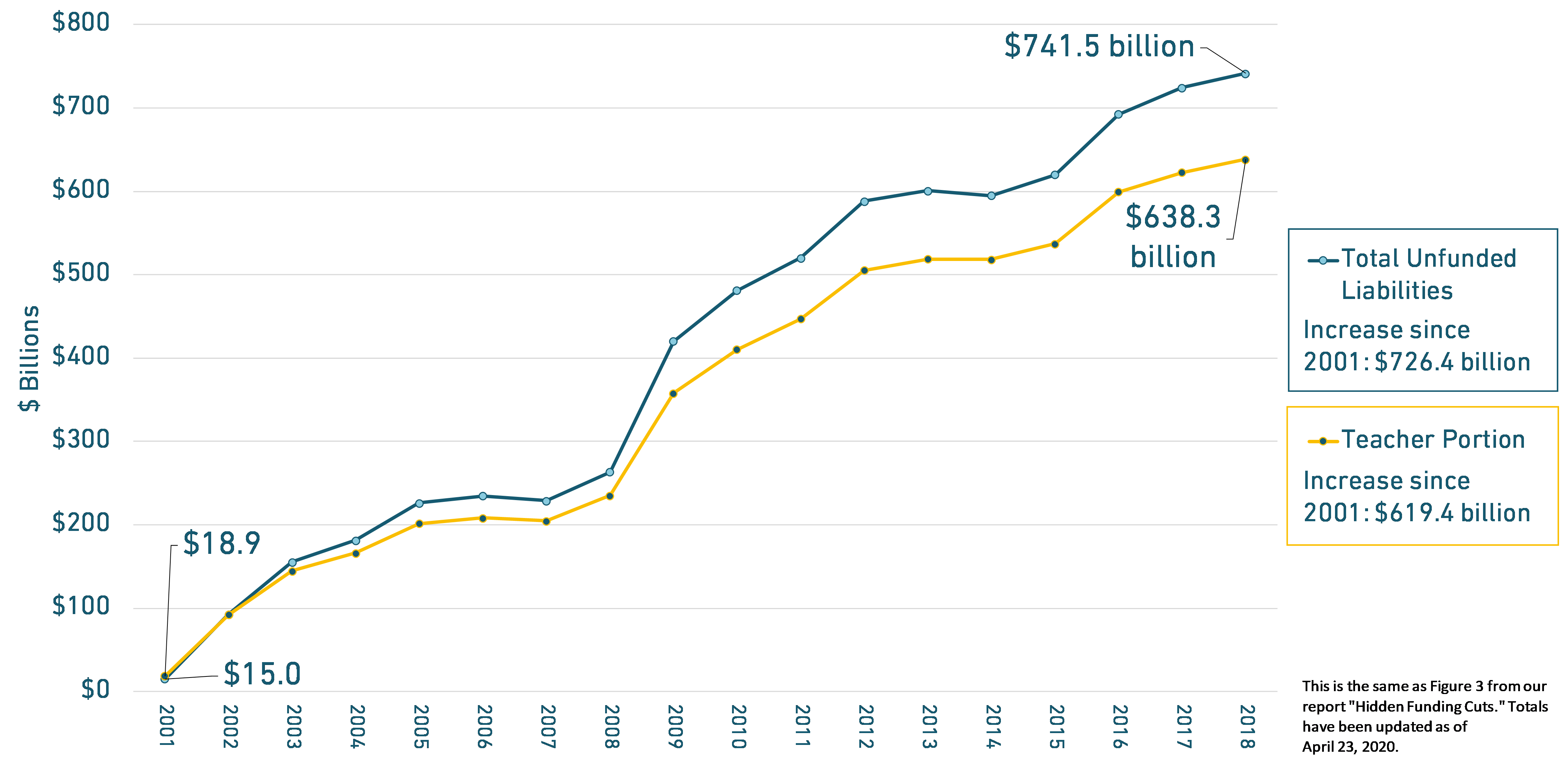

The pension funding shortfall for statewide plans that include teachers reached more than $740 billion in 2018. Teachers and other public school employees benefits have roughly $640 billion of that shortfall. [Click for large image]

Total Pension Funding Shortfall for Plans with Teachers and Share of the Pension Funding Shortfall Specific to Teachers (Actuarial Value), 2001–2018

When looking at the largest state and local retirement systems across the country for all kinds of public workers, the funding shortfall is roughly $1.6 trillion. Many of those plans are specific to employee types, like public safety or municipal workers. The funding shortfall of pension plans that include teachers is about $740 billion, as shown in the figure above. That number includes some state and city employees that are in the same pension systems. The portion of those unfunded liabilities attributable to teacher pension benefits, along with some other public school employees, is about $640 billion.

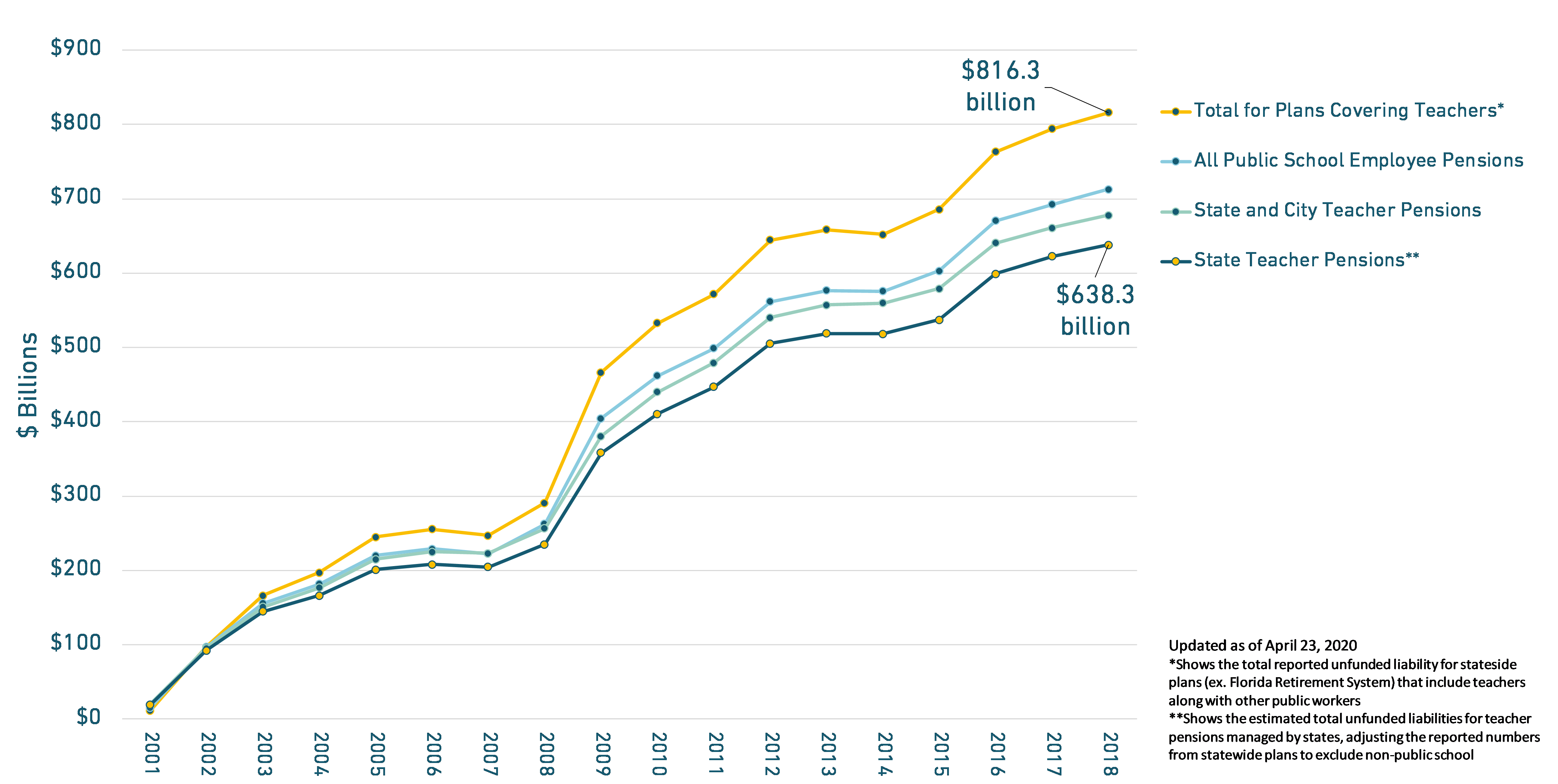

But there are other reasonable ways to estimate the value of promised teacher pensions and what the funding shortfall on those plans is. The most common reason why numbers differ when reporting on how much the funding shortfall is for teacher pension funds is a lack of clarity on who exactly is being counted in the total.

First, the common phrase “teacher pensions” could be referring to retirement benefits for classroom teachers or all public school employees.

In California, “certificated” employees are those who have a credential to work in a classroom, and could be teachers or administrators who have been teachers and maintain their credentials. By contrast, all other public school employees are considered “classified” workers. The pension fund CalSTRS is for certificated workers, while classified employees participate in CalPERS.

There are a four other states — Louisiana, Missouri, Ohio, and Washington — that make this same division and have totally separate retirement systems for school employees that are not classroom teachers.

Most states, though, put all employees at public schools in the same retirement system, whether or not it is called a “teacher” pension fund. For example, Michigan and Pennsylvania have large pension funds called the “Public School Employees’ Retirement System.” Meanwhile, in Texas and New York the “Teachers’ Retirement System” is actually for more than just teachers.

The $638 billion estimate above includes all statewide pension plans that provide benefits to classroom teachers. However, these plans also include more than just teachers in many cases. That means the number includes other public school employees from Michigan and New York (because they get the same benefits as teachers and there is no differentiation in the data), but not from California or Missouri (who have separate plans for non-teacher public school employees).

It would be reasonable to add the unfunded liabilities from California’s classified workers, and the separate school employees systems from Louisiana, Missouri, Ohio, and Washington. In this case the funding shortfall for all public school employees in state funds would add $35 billion to the total for 2018, of which roughly $27 billion is from the CalPERS plan for classified workers.

Second, some states bundle teachers into statewide pension funds that include other employees, and they aren’t always separated out.

In South Carolina, Nevada, and a dozen other states, teachers have the same benefits as state and municipal employees. A few states, like Maryland, provide data that shows teacher benefits, assets, and unfunded liabilities separately. But most don’t.

To figure out that half of the Florida Retirement System’s $30 billion unfunded liabilities are for public school employees, we look at reports that list out all of the participating employer units in FRS. Every state provides reports that show the share of liabilities for each employer, based on guidelines provided from the Government Accounting Standards Board. For any given school, academy, or school district the share of the total is very small. But when we identify all of these employers in Florida that provide services to K–12 students, the shares add up to roughly 49% of the unfunded liabilities for FRS.

This approach can be applied to all retirement systems where teachers are bundled in with other public employees, and estimate the share of the funding shortfall based on the share of employer participation. These figures are not as precise as using the raw data from each pension plan, but they don’t report those publicly. Using this method produces a reasonable estimate that will be close to the actual number.

Sometimes analysts won’t make these adjustments and they’ll just report the total unfunded liabilities for retirement systems that include teachers, and as of 2018 data that number is $741.5 billion, slightly higher than our estimate of $638.3 billion.

Third, there are a few cities that have their own teacher retirement systems. These are sometimes counted in reports, and sometimes not.

A truly comprehensive estimate of teacher pension funding shortfalls should include data from New York City, Denver, Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and St. Paul, which all manage their own teacher retirement systems.

These municipally managed retirement systems are not formally the responsibility of the state legislature and state budget, and so are sometimes not added to unfunded liability estimates for states themselves.

As of 2018, the six municipal teacher pensions have a $39.8 billion shortfall.

The following visual gives a sense for how bad the funding status is for retirement systems serving public schools across the country, based on who is counted in the shortfall.