Equable Institute’s recent issue brief on education funding cuts driven by growing teacher retirement costs identified several key problems states and school districts face as a result. Depending on how states share the costs of pensions – and pension debt, in particular – with school districts, there are several policy levers that can be used to solve this complex challenge.

Problems | Solutions | State-Specific Recommendations

The Problems

Here are the problems identified throughout the issue brief:

- Public school and teacher retirement systems have accumulated hundreds of billions in unfunded liabilities, and this has pushed up required contribution rates.

- State and local budgets for K-12 have not increased at the same rate as these growing pension costs, which has translated into a hidden education funding cut.

- The way that this pension cost crowd out of K-12 budgets has manifested has not been equally distributed or universally understood — both because some states manage their teacher pension funds better than others, and states vary in how they pay for retirement costs.

- Half of the school district leaders in states where the legislature covers costs on behalf of districts say that growing pension costs generally have reduced K-12 resources. One-third of school district leaders in states where all or most pension costs show up in district budgets say can point to specific expenses they’ve cut or deferred in the last five years because of the pension debt cost growth.

- Part of the variance in how school districts have experienced the effects of pension debt growth is due to differences in local resources—wealthier districts have more capacity to change local revenues to account for ways the state is passing along retirement cost increases. Larger and more suburban districts were also more likely to report cuts and deferred expenditures because of pension cost growth.

The Solutions

Permanently solving these problems requires improvements in state policy for managing their retirement systems. However, until such policies are effectively implemented education finance policy needs to immediately adapt and ensure there aren’t near-term harms to the K-12 education system being created or perpetuated.

To address the problem of pension costs creating K-12 education funding cuts generally, as well as ways that they can exacerbate resource inequities specifically, we recommend the following principles, each of which can guide the different kind of policies needed based on how a state divides up who pays for the pension costs.

1. Monitor Hidden Cuts

Annually review the share of K-12 state and local resources that are consumed by retirement cost expenditures — whether paid by districts or on their behalf by the state. When this share is increasing the state should adopt policies to increase K-12 funding to match.

Policy Approaches

-

- Increase state appropriations to K12 to match growth in retirement costs.

- Allow local districts to collect and keep increased revenue to cover pension costs for the collection of increased K-12 resources at the district level.

Policy Goals

It is bad policy for a state legislature to limit a necessary increase in retirement contributions simply to prevent district costs from increasing. This can lead to underfunding of the state retirement system and the perpetuation of cost increases in the future. Instead, states should allow for pension costs to be driven by appropriate actuarial assumptions and funding policies. If costs are rising for school districts relative to K-12 budgets then the state should increase funding to match these costs.

2. Don’t Make Districts Pay Pension Debt

Do not require school districts to cover the cost of unfunded liability amortization payments using funds intended for K-12 educator salaries, facilities, or programs.

Policy Approaches

-

- Have the state pay unfunded liability amortization costs directly (see rules in Maryland and Maine).

- Reimburse school districts for pension debt costs (see Pennsylvania policy).

Policy Goals

School districts do not have any immediate control over state pension funds and should not have their general resources consumed with pension debt costs. If the state does not fully offset the growth in pension debt costs, it should annually review how the effective education funding cut from retirement cost growth is influencing funding based on district size, wealth, urbanicity, and student demographics. An intermediate policy would be to provide selective support to districts that are particularly struggling for resources and are feeling an outsized effect of pension cost increases.

3. Require Districts Share Some of the Normal Cost

Do require that school districts contribute some portion of the “normal” retirement benefit costs, an amount sufficient to ensure they are incorporating the effect of retirement costs in their salary decisions and negotiations.

Policy Approaches

-

- Districts pay all or a portion of the normal cost directly to the state retirement system.

- The state could reroute district pension contributions from the state’s K-12 distributions after appropriation but before the dollars get to the district budget.

4. Review the Balanced Resource Effects of Pension Subsidies and District Requirements

A basic principle of state education funding is to ensure that all basic costs for providing education are covered while assessing the ability of local jurisdictions to cover those costs. Implicit in this framework is the recognition that school district resources vary, generally driven by the socioeconomic conditions of the community that district serves. For the purposes of assessing the effects of pension cost expenditure on these broader efforts to balance resources across a state, there are two types of actions that states should consider:

1) Assess the distribution of any state pension subsidy (e.g., a direct payment by the legislature of pension costs on behalf of school districts) across socioeconomic lines to ensure that higher resourced districts are not getting an outsized share of the state’s subsidy due to their stronger ability to pay and retain educators. If there is an imbalance then adopt a policy to either realign incentives or enable lower resourced districts to compete.

For example, Connecticut’s per-student pension subsidy is inequitably distributed as it is currently roughly 50% higher for students in high-income school districts. By contrast, Texas has a more equitable distribution of its per-student subsidy which has no variance on average based on underlying school district wealth.

Policy Approaches

A major driver of inequities is the ability of a wealthy school district to use their greater resources to pay teachers relatively higher salaries compared to surrounding districts. Two explicit policies that would influence this this are:

-

-

- Requiring those wealthier districts to pay all or a portion of the normal cost of pension benefits (giving some advantage to the lower resource districts who do not have this cost), and/or

- Increasing school funding formula weights and appropriations to the lower resourced districts to account for this imbalance.

-

2) Assess the effects of requiring school districts to cover the cost of pension costs (whether normal costs or unfunded liability payments) across socioeconomic lines and determine whether particularly low resourced school districts should receive certain temporary exemptions that support the states broader balanced resource goals.

For example, Michigan created a cap on the amount that school districts contributed to their public school retirement system at 20.96% of payroll, which for the last decade has been around two-thirds of retirement costs. This cap was later lowered that rate to 15.96% of payroll, with the state covering any required contributions above that line (a bit more than half of costs). This level is still above normal costs —meaning school districts are still contributing to the costs of unfunded liabilities — but the policy has moved in an appropriate direction.

Policy Approach

-

-

- Ensure that the state’s contribution is at least sufficient to cover the costs of unfunded liability amortization payments — e.g., pension debt costs.

-

5. Integrate Retirement Costs Explicitly into School Funding Formulas

States should directly incorporating a consideration of pension costs in their school funding formulas. State aid to school districts is generically intended to cover basic education needs, but if pension costs are only implicitly covered in these appropriated dollars it is more likely that policymakers will unintentionally allow for hidden education funding cuts to grow.

What Actions Do States Need to Take?

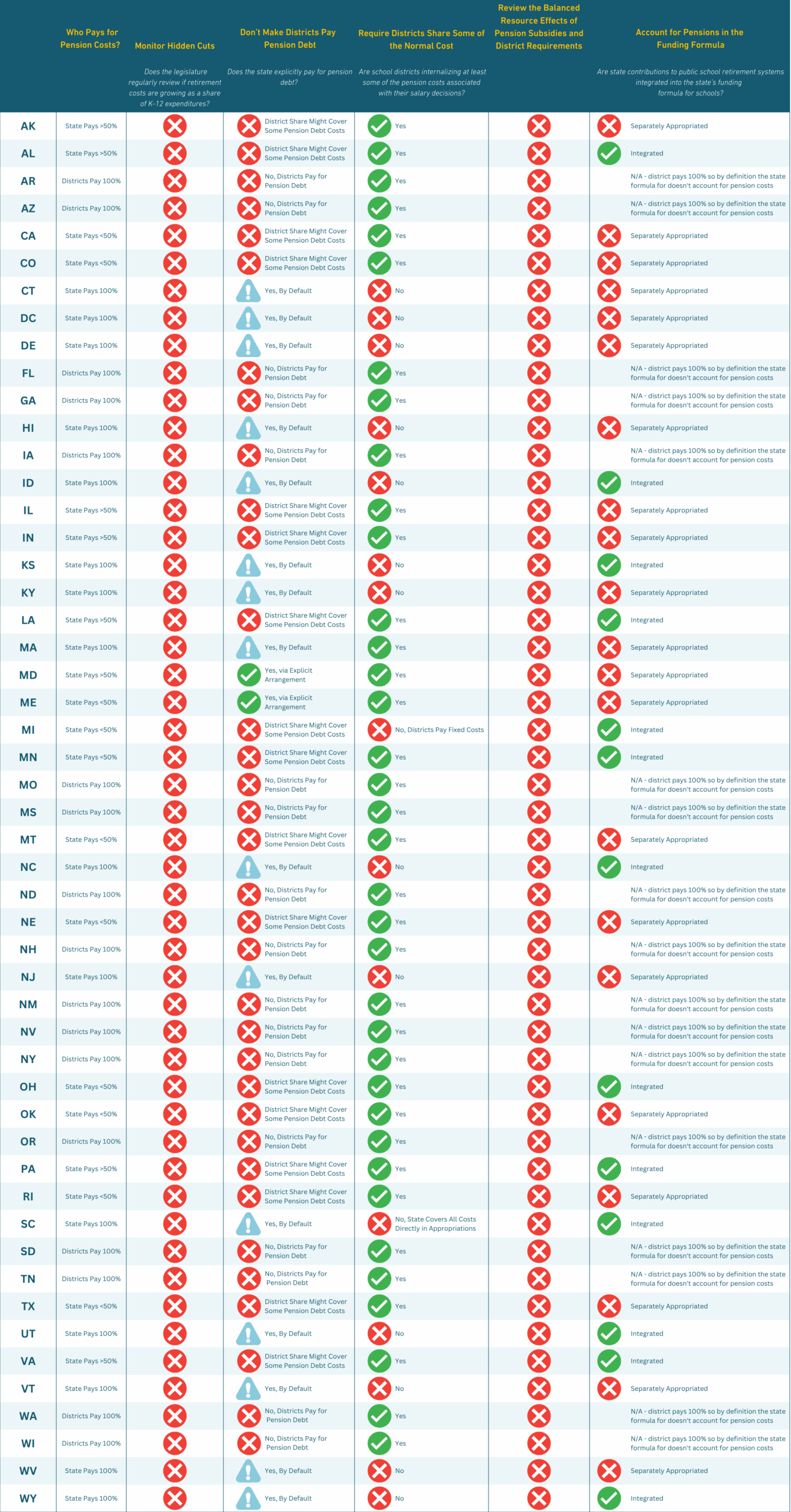

The below chart assesses how each state performs against the above policy recommendations.