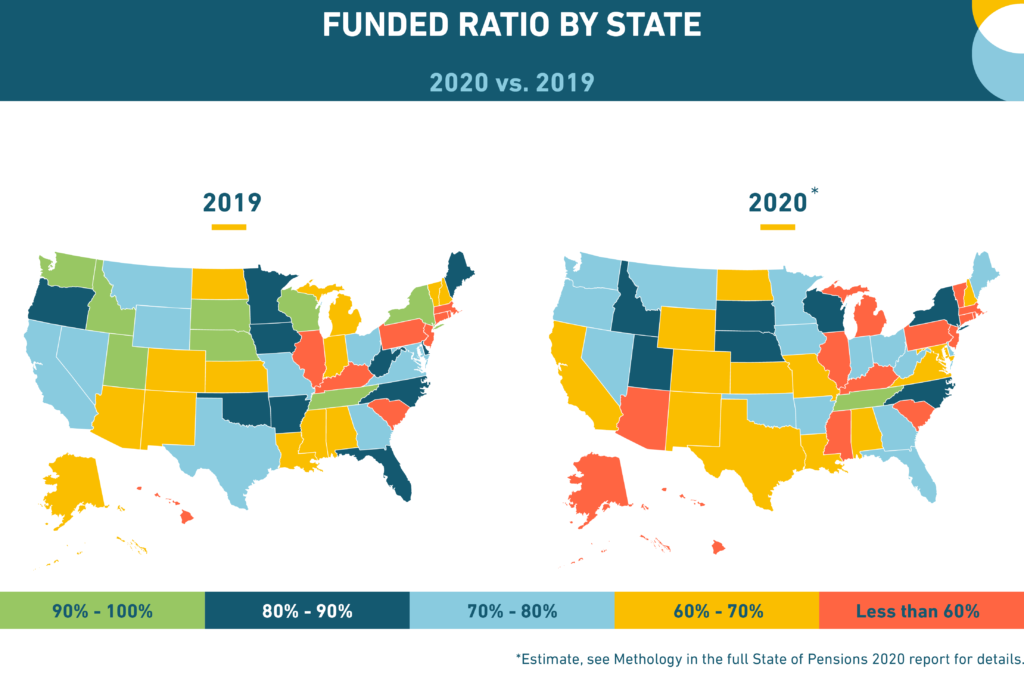

Equable Institute estimates that only one state, Tennessee, will maintain its resilient funded status in 2020, as a result of the losses and underperformance caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic Recession.

U.S statewide pension funds entered the COVID-19 recession profoundly weaker than they were financially going into the Great Recession, a new report on national pension funding trends from Equable Institute shows. In this post we will look at the core reasons behind the modern public pension fund’s systemic vulnerability. While America’s recent period of economic strength bolstered earnings on Wall Street, the 11-year growth in investment earnings failed to close the national pension funding gap. Actually, the funding shortfall for statewide pension funds expanded over the past decade, and mandatory paycheck contributions for public employees increased.

State of Pensions 2020: Public Pension Debt is Rising

What is the public pension funding gap in 2020?

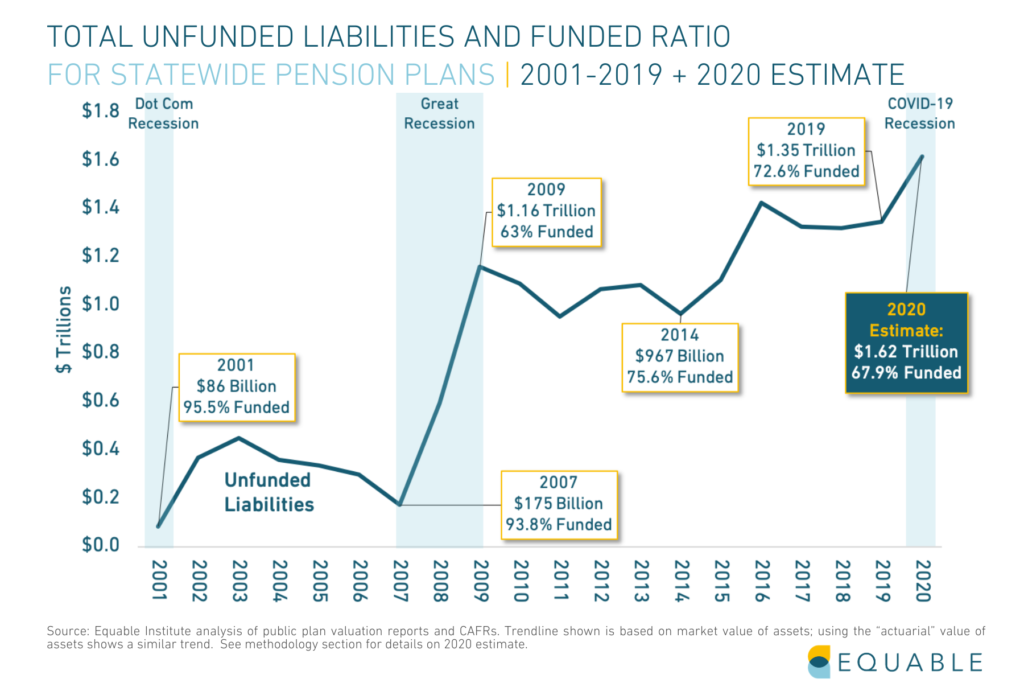

The national pension funding shortfall for statewide retirement systems was $1.35 trillion at the end of 2019, per Equable Institute’s State of Pensions 2020 report. The funding shortfall — formally called unfunded liabilities — is the gap between money held by pension funds and the value of all future benefits it has promised to pay. This is also sometimes called pension debt.

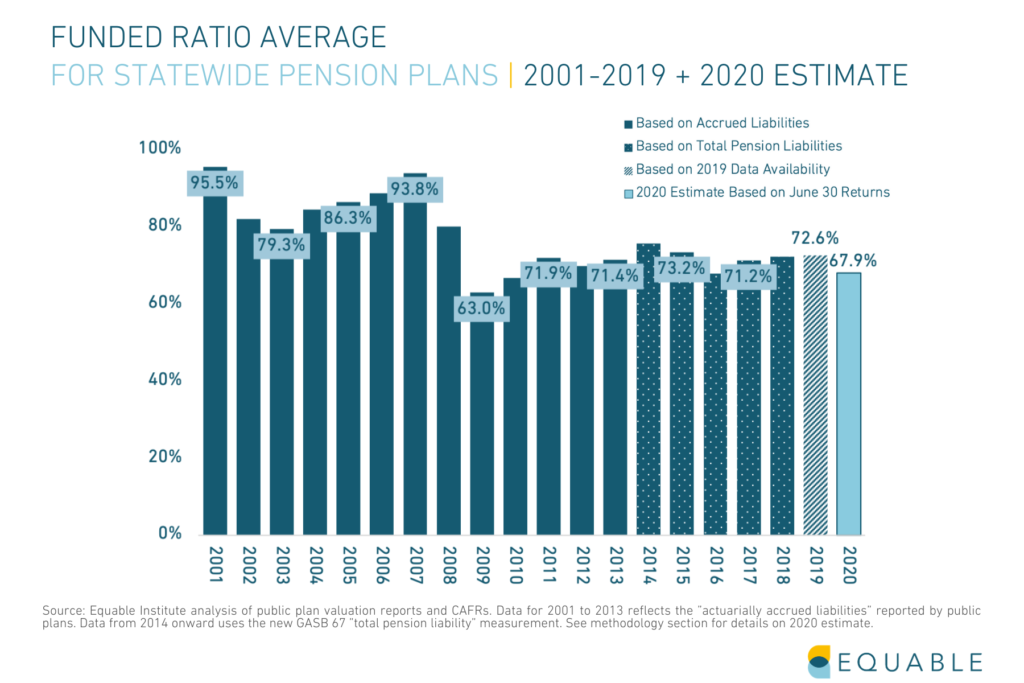

Equable Institute’s report estimates that this shortfall will grow to more than $1.6 trillion in 2020 as a result of COVID-19 losses and underperformance. On average, this means that American public pension plans are currently holding only 67.9% of the assets required to pay future retirees their pension benefits.

By contrast, in 2007 before the Great Recession, statewide retirement systems in the U.S. had 93.8% of the money promised to current and future public retirees. Losses because of the Financial Crisis of 2008 knocked this funded ratio down to 80%. And as of 2019, before the COVID-19 Recession, the average statewide pension fund was roughly 73% funded.

Equable Institute found that the aggregate funded ratio for U.S. public pension funds was lower in 2019, going into the pandemic economy than it was in 2007 going into the Great Recession of 2008.

All of this means that pension funds never fully recovered from the economic losses of the last recession. Which suggests many pension funds in the U.S. will have a harder time achieving full funding coming out of the COVID-19 Recession, as they have entered the economic downturn in a weak position.

Why is the national pension funding gap growing?

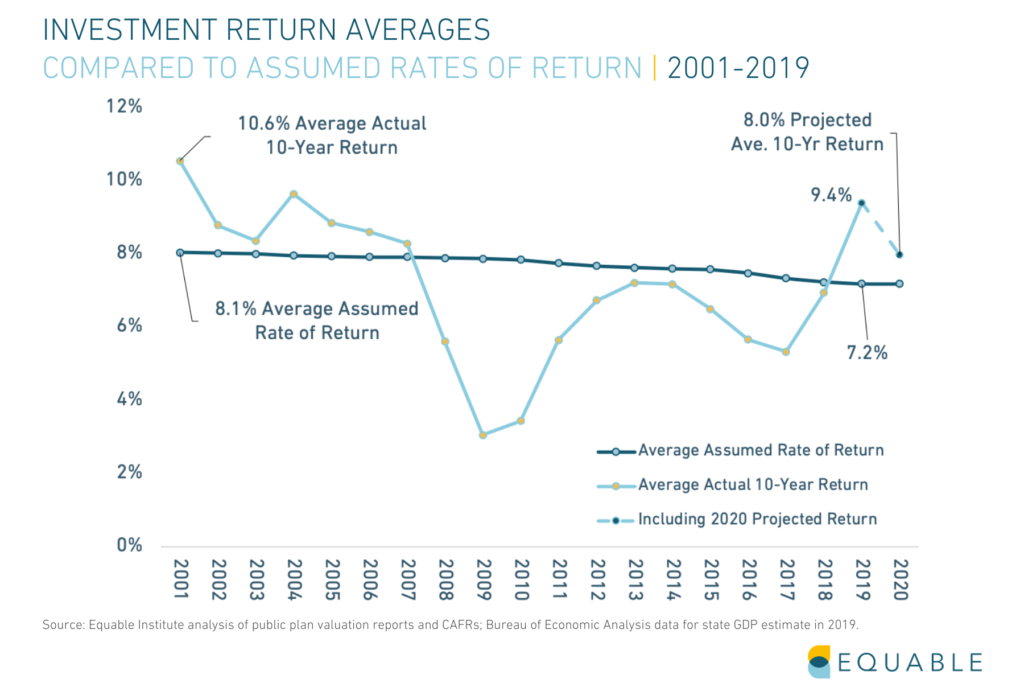

Public pension systems use an assumed rate of return to calculate what dollars will be needed to cover pension benefits due to future retirees. When there is a large gap between (a) the actual returns pension funds receive from their investments, and (b) the rate that they assume they will earn, then (c) pension funding shortfalls grow.

For several years, a significant gap between projected earnings and fiscal reality has existed for public pension plans in many states. Still, the assumed rates of return used by many statewide retirement systems have remained significantly higher than actual investment earnings. A handful of states have meaningfully reduced their assumed rates of return in response to economic shifts.

In State of Pensions 2020, Equable Institute shows that assumed rates of return have been overly optimistic, when compared to actual investment returns for the same period (2001-2019). Most years since 2007 have underperformed, leading to a growing funding shortfall.

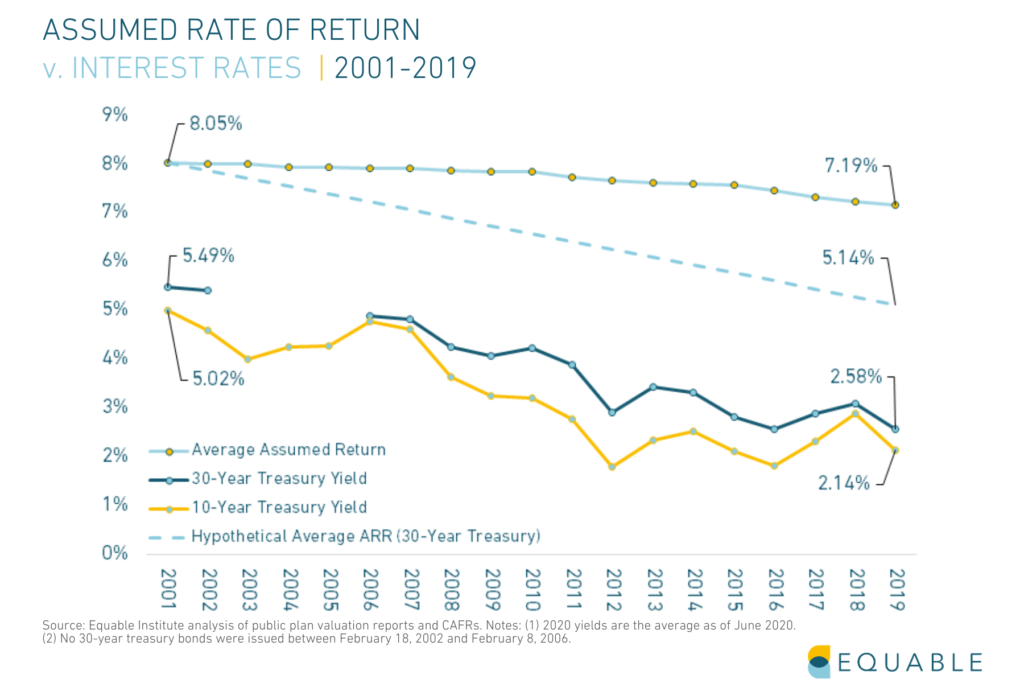

Interest rates are considered an indicator of future market performance. Declining interest rates indicate that investments will likely see slower investment return gains in the future. This is important because it means that historic performance is not a good indicator of future performance. Many pension funds report that they have had strong investment returns over the past 30 or 40 years — and this is true. But unfortunately those numbers do not actually mean very much for the future. They include investment returns from the 1980s or 1990s, which were very different economic times.

While interest rates over the past two decades have rapidly declined, pension fund assumed rates of return have not kept pace. Meaning many funds are either over-estimating what their investments will earn or they are making a lot of high risk, high reward investments to try and hit their optimistic targets.

The chart below shows the recent trend in assumed rates of return in tandem with interest rates. They have not kept pace with each other. Today, the average assumed rate of return for statewide pension funds is 7.2%. If assumed returns had kept pace with declining interest rates since 2001, the average assumed rate of return in 2019 would have been around 5.1%.

Equable Institute estimates that if assumed rates of return for U.S. public pension funds had kept pace with interest rates since 2001, the average assumed rate of return would be 5.1% today. It is 7.2% as of 2019.

The often highly optimistic assumed rate of return used by most pension funds to make financial decisions may be increasingly hard to achieve if America’s path to economic recovery remains uncertain.

How does national pension funding debt affect public workers?

The pension debt carried by governments is costly to pay down and creates pressure on the public budget. It may cause an increase in required pension contributions for public employees or benefit reduction like the elimination of cost-of-living (COLA) adjustments for retirees. In times of economic hardship, it may result in higher property taxes, delayed raises, cuts in school funding, and a reduction in essential services like public sanitation.

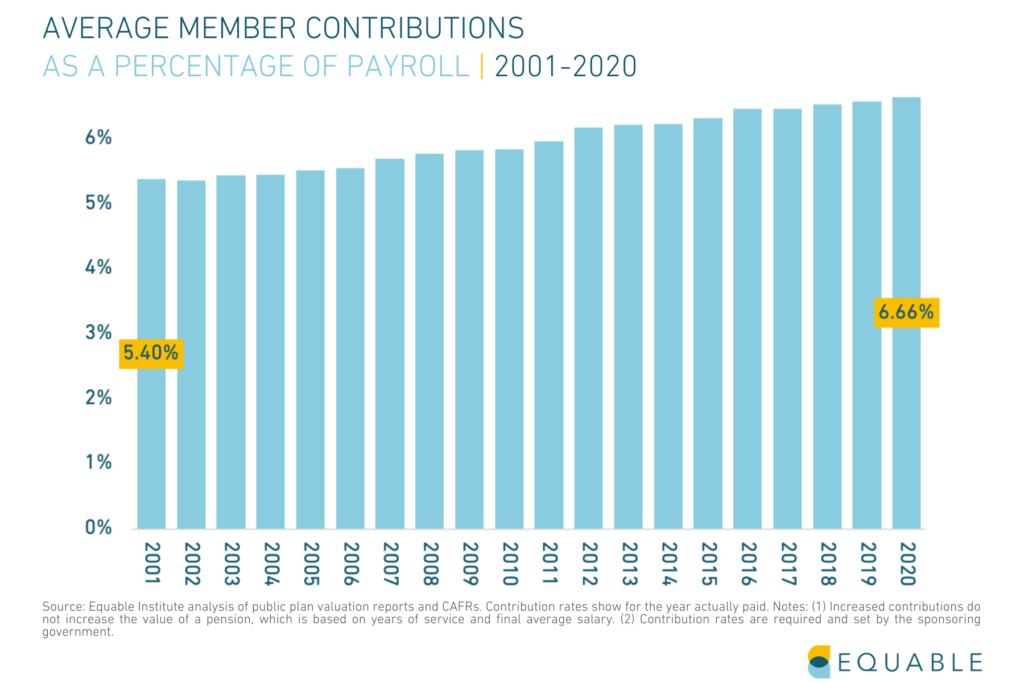

Public employee paycheck contributions have grown significantly over time, due to rising pension debt and risk-sharing policies in many states.

State of Pensions 2020: Public Pension Plans Are Open to More Risk

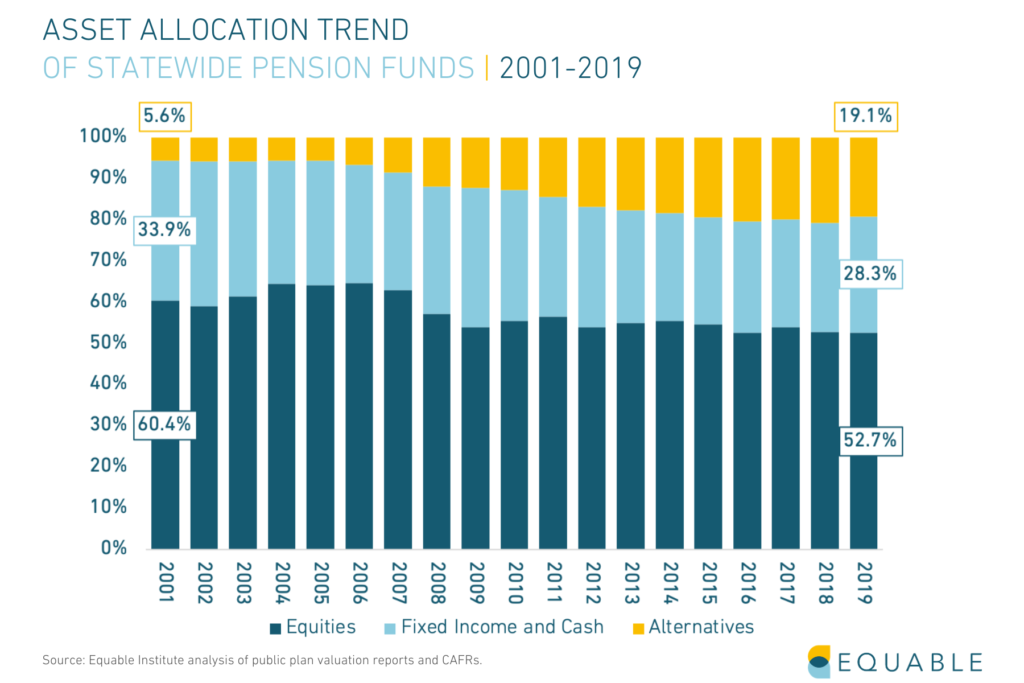

Public pension plans have increasingly moved away from a reliance on relatively safe fixed-income investments during the past decade, per Equable Institute’s report.

Since 2001, pension funds have placed a higher percentage of their assets into hedge funds, real estate, and private equities, investment categories known for volatility in times of economic uncertainty.

Equable Institute reveals that U.S. public pension funds have progressively shifted their assets into riskier investments.

Some of the alternative investments that state pension funds have adopted might produce higher returns and might help hedge against sharp downturns in the stock market. But they also carry much higher risks that are only justifiable if the objective is to try and earn an unreasonably high assumed rate of return target.

The State of Pensions 2020: Most Public Pension Systems Are Financially Fragile or Distressed

What does public pension underfunding mean for states?

As the prospect of a resilient stock market dwindled when the pandemic took hold of the economy in 2020, so did the possibility of many pension funds receiving their projected investment returns.

Compounding this is the effect of the pandemic’s disruption of tax income. This revenue is essential for states being able to make their required contributions to fund pension benefits. That combined with underperforming investments means it is likely that pension debt (or unfunded liabilities) will likely continue to grow in the coming years.

Equable Institute projects that pension debt will grow to $1.6 trillion in 2019.

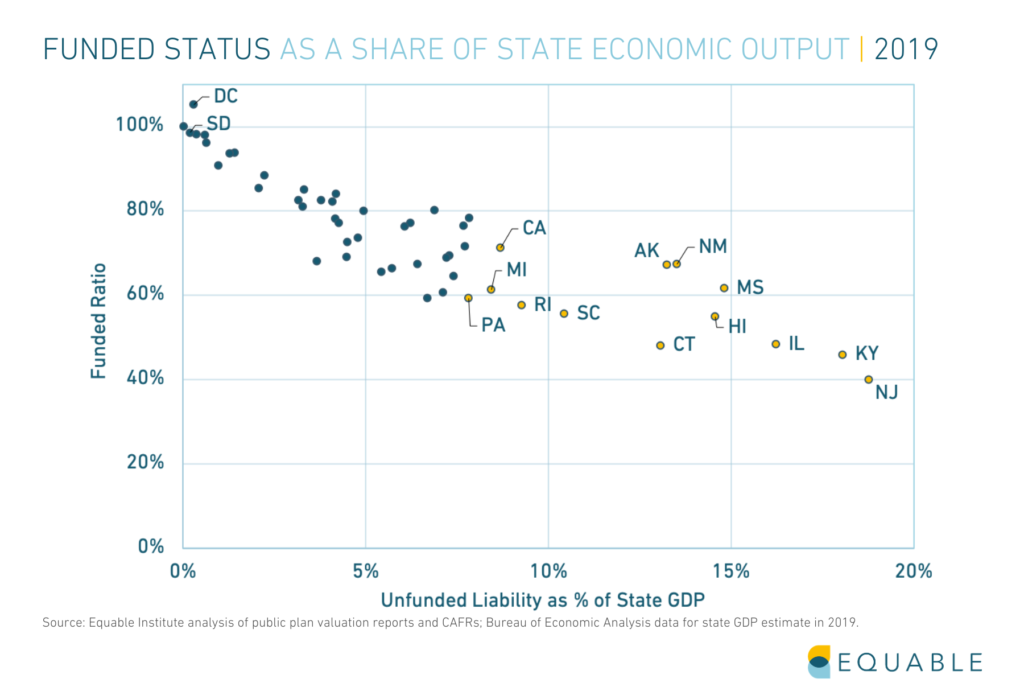

The funded ratio and pension funding shortfall are not the sole indicators of the health of a pension plan. Understanding the size of unfunded liabilities relative to the size of a state’s economy gives a sense of what scale of resources will be needed from a local tax base to improve funded status.

Prior to the pandemic, unfunded liabilities already accounted for a large share of states’ GPDs. In some states, like Illinois, Kentucky and New Jersey, pension debt tops 15% of the state GDP, a significant challenge for a government even in a strong economy.

Equable Institute found that states with pension funding challenges often have a high rate of unfunded liabilities relative to GDP.

Today, only one in five statewide pension plans are considered economically resilient, according to the Equable Institute report, which means holding assets that cover 90% or more of promised public employee pension benefits for at least a few consistent years.

How will underfunded public pension funds cover promised benefits for workers?

There are three strategies that states might take in seeking to ensure they can pay promised benefits to workers: increase contributions into their pension funds, pursue higher investment returns, or reduce the value of benefits.

Cutting benefits is unconstitutional in nearly every state, but in certain places benefits have been reduced by cutting back on the inflation adjustment of pension checks.

Pursuing higher investment returns has been the primary strategy of the past decade. While a few state pension plans were able to recover and some years produced good returns, overall investment returns have not been high enough for everyone to recover. States will continue using this strategy, but it has high risks. And if it doesn’t succeed that leaves only the other two strategies.

The other key strategy is increasing contributions. Usually, when unfunded pension liabilities rise steadily over the years, employer contributions experience an uptick along with required employee paycheck deductions. Just throwing more money into state pension funds doesn’t always help, though, if the underlying reasons that the funding shortfall is growing in the first place are not addressed. That means pension debt and employee contributions may rise unabated until a change in policy mandates a reversal of problematic practices. Even a boon in investment returns has historically offered no guarantee that state and local governments will make debt payments in a timely fashion.

The pandemic has illuminated the financial challenges facing many public pension funds across the country.

To learn more about public retirement benefits in your state, check out the interactive Retirement Security Report.