Fitch Ratings released a report last week evaluating the asset allocations of the largest public sector pension plans in the U.S.

They ranked states based on the level of investment risk in each state’s largest pension funds, and measured the performance of states over the past few decades against their own assumed rates of return.

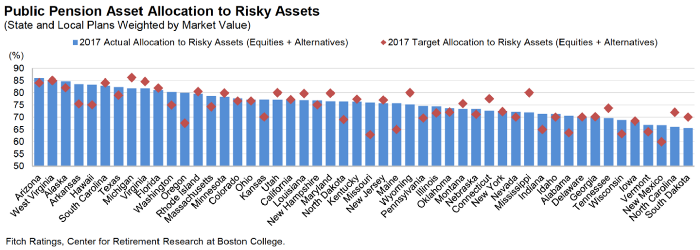

Specifically, Fitch measured the percentage of a given pension fund invested in“equities and alternatives,” and ranked state pension funds with the largest allocation to these asset class categories as having the most risk. Based on this approach, the riskiest state in the country for pension investments, according to Fitch, is Arizona.

The methodology used by Fitch weights the major plans in each state by market value of assets, so for Arizona the ranking is heavily influenced by the State Retirement System (ASRS, with $40.2b in assets as of last year compared to $7.3b in the Public Safety Personnel Retirement System).

It is worth noting that these figures are based on fiscal year end 2017 data, and since then ASRS — the largest system in Arizona — has actually moved to expand its portfolio of real estate and private equity investments. Currently, ASRS is assuming a 7.5% rate of return, which according to their own investment advisors only has a roughly 50% probability of success. This is one reason that the Urban Institute recently wrote, in a paper analyzing ASRS, that the pension fund is in a somewhat precarious position.

The Pension Integrity Project also analyzed ASRS, and benchmarked the pension fund’s portfolio against capital market assumptions from a range of respected financial firms, and found the probability of hitting a 7.5% rate of return ranges from 20% to 30% (see slide 16 in this report).

Arizona is certainly not alone with its heavily equities and alternatives portfolio. According to Fitch, West Virginia and Alaska are close behind. Michigan also appears to be targeting a riskier portfolio than Arizona, but hasn’t quite allocated its assets according to those internal targets.

Taking on large amounts of risk is not inherently problematic. Alaska, for example, has large ebbs and flows in natural resource revenue, meaning state leaders might feel they have the capacity to cover for underperformance. On the flip side, West Virginia might be allocating to risky investments because it is resource-constrained in being able to make contributions required assuming lower investment returns.

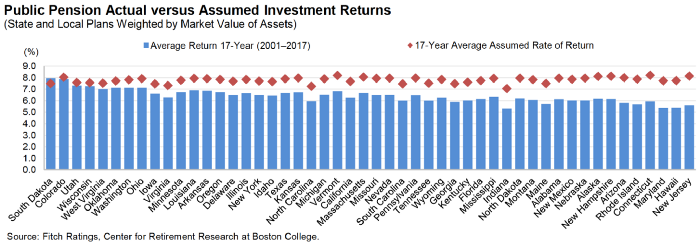

For Arizona, though, the level of risk taken is complicated by the historic performance of investments. Fitch data, which again, comprises investment returns for more than just ASRS, but is heavily weighted towards ASRS due to its size, shows that Arizona has been among the six worst performing states relative to assumed rates of return.

The average assumed return in the Fitch data for Arizona is 8%, but the average actual return from 2001 to 2017 is less than 6%. This is a considerable shortfall, but does not mean that Arizona’s funds have necessarily been bad investors. Many other pension funds earned actual returns lower than Arizona. And while PSPRS is a notably poor investment performer, ASRS in particular has been among the better performing pension funds in the country. What it means is that Arizona’s pensions plans have underperformed their targeted investment assumption.

Because pension plans(specifically final average salary-style defined benefit plans) are based on contributions and investment returns being enough to pay for promised benefits. But what is most important is the plan’s investment performance performance relative to their return assumptions. Indiana, for example, has barely earned more than 5% since 2001 (as can be seen in the chart above), but it was also targeting a much lower investment return than Arizona. Because Indiana’s returns have been closer to the investment target, they are ranked higher in this category than Arizona.

Collectively, this report from Fitch is yet another signal that public plan stakeholders in Arizona should be reviewing the levels of risk associated with their retirement systems and consider how to improve funding policy to ensure long-term sustainability. Labor leaders (in particular teacher groups), municipal employers, and other management stakeholders should be looking to collaborate with legislative leaders on a plan to address the levels of investment risk among Arizona’s pension funds.

To learn more about the funding challenges facing ASRS, check out our previous post here.

This article was originally published on our Medium blog on May 14, 2019.