Pension Myths: The Funded Status of Pension Plans Does Not Depend on More Public Employees

Myth: More public employees are needed to ensure pension debt gets paid off.

Fact: Employee contributions typically only go toward the cost of their own benefits. Employees typically don’t make pension debt contributions, so money from future employees is not necessary.

A common misunderstanding is that pension fund financing works like Social Security, but that’s actually not the case. Social Security uses contributions from current workers, collected through tax collection, and uses the money to pay current retiree benefits. But pension benefits earned each year are intended to be funded in advance with contributions that will then earn investment returns.

Pension plans are funded using contributions from members, and employer contributions. The contributions from members typically only go toward the normal cost — the total contributions needed to pay for the pensions earned each year.[1] By federal law, retirement systems have to refund the value of member contributions if public workers leave their job before retirement and request the money back. If employee contributions were regularly used to backfill pension debt that would make funding status less stable.

This is an important distinction. For example, if the normal cost of your pension were 10% of payroll, and the pension system required employees to make contributions equal to 6% of their payroll, then those employee contributions go toward the normal cost of benefits and the government employer pays the other 4% of normal cost contributions plus any pension debt payments.

This arrangement — public employee contributions going toward normal costs — means that if a state legislature or city government wants to create a new retirement plan for future employees, it should be able to without jeopardizing the benefits of current retirees. The new retirement system could be another pension plan that has better risk management tools, something Michigan and South Dakota have done, or an alternative plan design to pensions. No matter what the new plan concept, it will not undermine the legacy pension plan because that legacy pension is not counting on future employee contributions to fund retirement checks. Current public workers only contribute to their own benefits in a defined benefit pension plan, so contributions from future teachers aren’t necessary to cover costs when they retire.

______________

[1] There are a few exceptions to the standard practice of employers paying for all of the pension debt costs. Arizona’s public employee pension plan — covering teachers, state workers, and municipal employees — uses a 50/50 cost-sharing model where employees cover half of the pension debt payments. Ohio’s teacher pension plan has member contributions that are higher than normal cost.

Pension Myths: The Assumed Rate of Return Does Not Determine the Value of Benefits

Myth: The assumed rate of return determines the value of your benefits.

Fact: The value of your benefits is determined using a formula completely separate from the assumed rate of return.

While pension funds do their best to predict investment returns, the assumed rate of return is just that—an assumption. It depends on external forces that pension systems can’t control, and assuming a rate of return provides no guarantee that investments will actually earn that rate. Rates of return could be, and often are, significantly higher or lower than assumptions.

Benefits are determined using a formula that takes into account years of service, final average salary, and age related qualifications to start receiving benefits.

Case Study:

The Teachers Retirement System of Texas (TRS) assumed for more than three decades that it could earn an 8% return on its investments. This was a long-term projection, so when the economy hit a recession in 2001, they didn’t change it. When they lost money in the Enron scandal, they didn’t change it. Even after the financial crisis of 2008–09, they didn’t change it.

Over the past two decades, TRS earned positive investment returns. In fact, from 2001 to 2018, there were nine times when annual investment returns were larger than 8%. Unfortunately, the years where investment returns were lower than expected began to add up.

The average investment return for TRS between the time when the pension was last fully funded (2001) and today was around 6%—less than the 8% predicted. Even worse, financial advisors now believe that the odds of TRS earning an 8% return in the future are just 1 out of 5. TRS recently lowered its assumed return to 7.25%, trying to be more conservative in its future outlook. They might lower it again in the future.

This reduction in the assumed rate of return did not change the value of benefits provided for retired or active teachers. They will still get the same pension benefits promised to them. And this because the value of benefits is not based on the assumed rate of return in any way.

Pension Fund Governance

Managing guaranteed income plans is complex. In most states, a board of trustees that represents different stakeholders in the pension plan manages the system. Such stakeholders typically include teachers, retirees, the legislature, the treasurer’s office, and the governor. Some states also have independent members that represent the financial community or taxpayers, while others have an auditor, comptroller, or other oversight official on the pension board.

Ultimately, pension systems vary a great deal in the number of trustees, the stakeholders they represent, how they are selected, and minimum qualifications. Well-constructed boards should give all stakeholders a voice in decision making; the exact balance will depend on preferences in a given place.

The pension board holds a fiduciary responsibility for administration of benefits and investment of assets, meaning they are bound to make decisions in the best interest of public workers. Given the complexity of pension board responsibilities, governments should make sure there are appropriate qualification standards for individuals to serve on the board. Retirement systems should also make sure they provide appropriate training for any board members who need it.

Funded Status

Government employers have made promises to public workers, that at retirement they will get guaranteed monthly income for life. But how do pension plans keep these promises? It all starts with one of the most important measurements a pension plan has: funded status.

Funded status measures the dollars a pension fund has received and invested, compared to the pension payments it needs to make.

Challenges with Funded Status

In recent years, funded status has been less-than-perfect for most public pension funds, due to growing pressures that pension boards and legislatures have been slow to react to:

- People are living longer, which means paying benefits longer than your pension board may have originally expected.

- Governments have failed to pay all of their pension bills on time.

- Investments made by your pension board haven’t performed as well as they predicted.

The result is a significant shortfall funded status. Government employers have to make up any shortfall in your pension fund’s assets, making debt payments.

In many states, the pension debt is billions of dollars. It’s getting harder to keep up — and you may be feeling it yourself. If you’re a public worker, your take-home pay might be getting smaller because you’re required to contribute more from each paycheck. Or raises might not feel as meaningful because your state has less money to increase pay. If you’re already retired and receiving a pension, you may be losing your COLA — or cost-of-living-adjustments — which helps you keep pace with rising prices.

Taxpayers may be feeling the decline in funded status too, just in ways not recognized. Property taxes might be up, road repairs might be delayed, or public investments in things like affordable housing or cleaner parks might be on hold.

Paying the Pension Bill

It is important that state and local governments pay at least 100% of their actuarially determined contributions (ADC) each year. The ADC is based on assumptions about how long public retirees will live, what kind of investment returns a pension fund can earn, and policies about how to backfill any shortfall in funding status, among other assumptions. It is kind of like getting a bill or invoice for services — actuaries for the pension fund calculate the contribution rates needed based on the rules and benefits authorized by a state or local government, and then figure out what that government should pay each year to fund the benefits.

When governments do not pay their pension bill, it is an almost certain path to the creation of pension debt.

Reasons Why the Pension Bill Might Not Get Paid

Fixed Rates — Some states and cities pay fixed contribution rates into their pension funds.

- For example, until last year the Texas state government paid a fixed 6.8% of payroll into its teacher pension system, and 9.5% of payroll into its state employee pension system.[1]

- The state government prefers to have these fixed rates so that the legislature feels a sense of control over what gets paid into pension funds.

- In isolation, this may be a reasonable concern. However, in practice, the fixed contribution rates that the Texas legislature has authorized have only been enough to pay 100% of the teacher pension bill in two of the last 15 years.[2]

Economic Recessions — It is common for governments to reduce their payments into a pension fund when tax revenues decline.

- For example, during the last recession (from 2008 to 2009), state tax income fell by 17% because of the slow down in economic activity.[3] This reduced the money available in state budgets by billions of dollars.

- One of the common choices for states during and immediately after the recession was to reduce the amount of money paid into pension funds to balance state budgets. Depending on the situation, this may be a reasonable policy choice given various competing interests and need for trade-offs.

- However, the states who followed best practice made sure to overfund their pensions in future years to make up the difference in shortchanging the pension bill in the past. Some states just went on as if they hadn’t stiffed the pension fund from the money it needed.

Pension Holidays — Sometimes pension funds achieve being 100% funded, meaning there is enough money in the pension fund to pay out all promised benefits, based on the current estimates of the value of pensions. In these cases, state and local governments have a habit of taking holidays from paying their pension bill (which would just include payments for normal cost). However, this can create problems because a well managed pension plan will use assets that are more than it needs today to cover future losses, and stay perpetually around 100% funding status.

Why Paying the Bill is Important

It can be very expensive and unpredictable for state and local governments to have to make pension debt payments for an extended period of time. Failing to pay at least 100% of the actuarially determined contribution each year — the pension bill — can mean causing a pension system to get mired in a funding shortfall. And that isn’t good for government budgets, municipal finance stability, or the retirement security of public workers.

______________________

[1] The Texas state contribution rate for teacher pensions is now scheduled to increase to 8.25% of payroll over five years, and school districts pay their own fixed contribution rate (1.5% of payroll today, 2% of payroll by 2025). For more, see Equable’s discussion of improvements to Texas Teachers Retirement System.

[2] See analysis developed by Equable titled Texas Takes Next Steps Towards Improving Teachers Retirement System Sustainability.

[3] See analysis of the recession from the Brookings Institution.

What are Actuarially Determined Contributions?

It is important that public sector pension funds receive adequate contributions each year in order to maintain a healthy funded status, or make progress on a plan to recovery. And the minimum necessary step for a state or local government to make adequate payments is to ensure they are paying 100% of the “actuarially determined contribution” (ADC).

Part 1: Payments to Backfill a Funding Shortfall

When pension plans have a shortfall in the money that should be available to earn investment returns and pay benefits, this is called an unfunded liability. To backfill that shortfall, the government sponsoring a pension plan needs to make payments — either regular contributions each year, or lump sums. Or both.

Contributing money to a pension plan to backfill a shortfall in funding is known as an amortization payment. These payments are similar to setting up a schedule to pay off a mortgage. Pension boards set policies for how they want to pay down an unfunded liability — such as fixed dollar payments each year for 20 years — and then an actuary calculates how much needs to be contributed annually.[1]

Because pension benefits have been promised to public workers no matter the funded status of a pension fund, unfunded liabilities are effectively a debt that is owed by the government to the pension fund. That is why unfunded liabilities are sometimes called pension debt. And similar to paying off a mortgage or credit card, the longer pension funds take to pay off debt, the more interest will add up, and the more contributions will have to go up to pay for it.

Part 2: Normal Payments for Benefits Earned Each Year

Actuaries estimate the total value of pensions that are expected to be earned each year, using educated guesses about how long people will work, what their salaries will be, how long they will live, and other factors. Then, those finance specialists recommend an amount that should be paid into the pension fund for benefits that have been earned this year — factoring in what those contributions will earn in investments. This recommended contribution is known as “normal cost.”

Combining “Normal Cost” and “Pension Debt Payments”

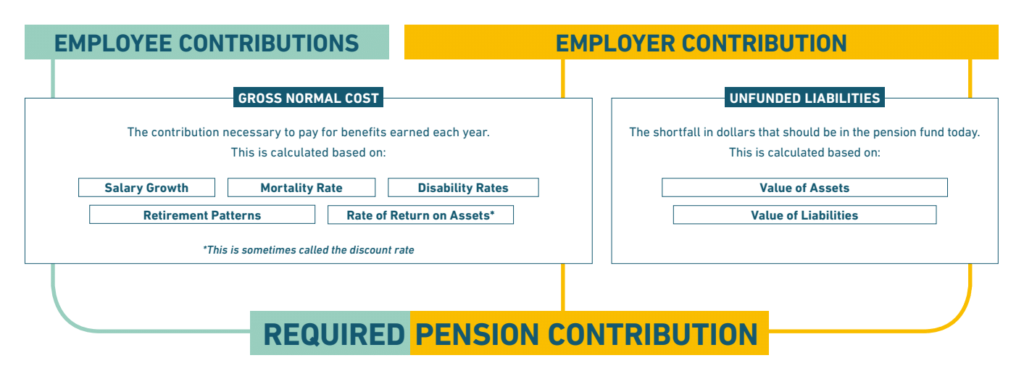

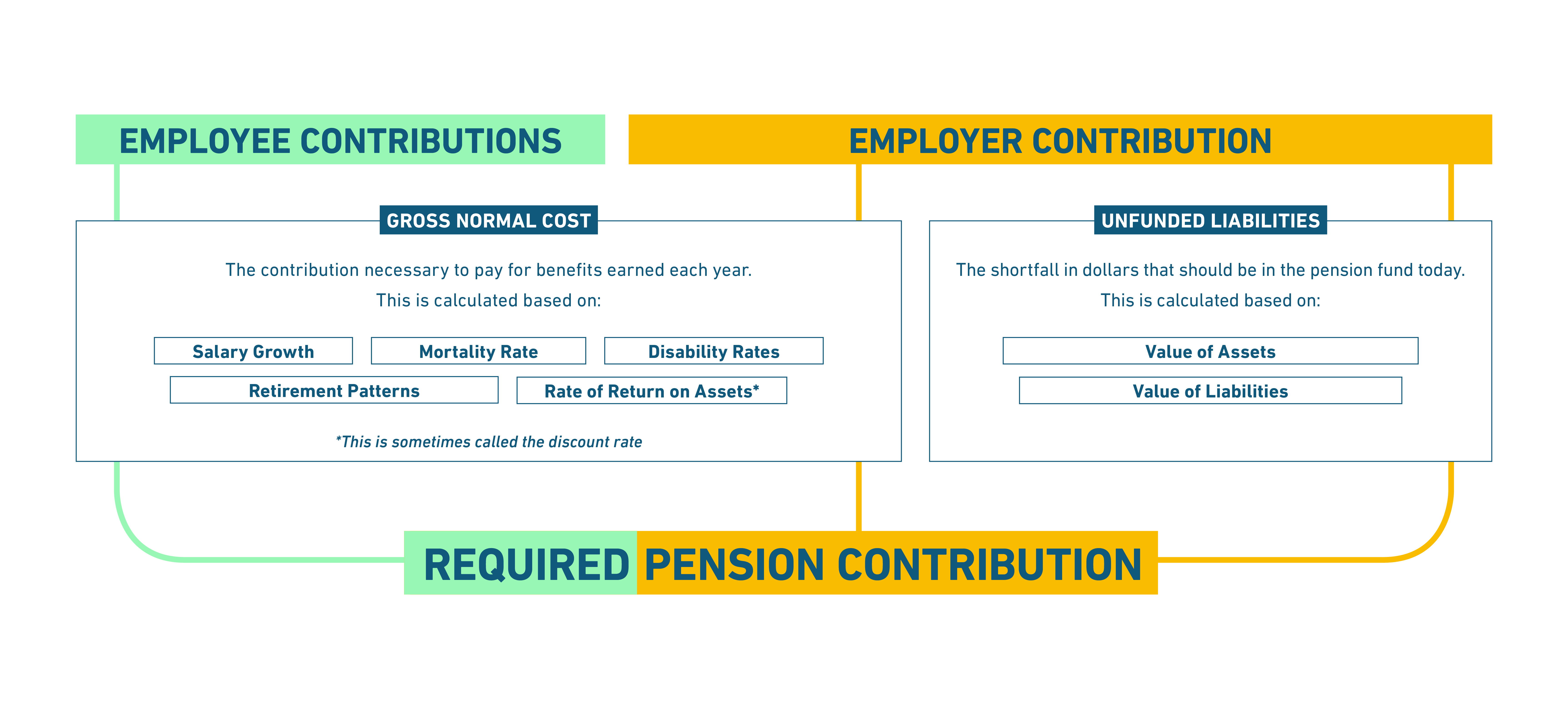

The annual, actuarially determined contribution rate is a combination of (1) normal cost for benefits earned during the same fiscal year, and (2) unfunded liability payments to backfill any funding shortfall that has occurred over time.

As the figure below shows, employee contributions typically are applied to normal cost first. Any remaining normal cost is paid for with employer contributions. Then employer contributions also go toward paying down the unfunded liability.[2]

The term “ADC” has emerged recently, over the past five years. For the decade before that, the combined total of normal cost and unfunded liability payments was sometimes called the “actuarially required contribution” or ARC payment.

In the balancing equation discussed earlier — B + E = C + I — the “C” is really the ADC, actuarially determined contribution. It is the amount necessary to pay benefits plus expenses, after accounting for an assumed investment return.

__________________

[1] Some pension funds have fixed contribution rates. The hope is that the fixed contribution rates are set close to the ADC, but often they fall short.

[2] Depending on how your state is structured, the employer share of the ADC might be paid for by the state directly, by a local employer — such as a municipality or school district — or a combination of the two.

Unfunded Liabilities (aka Pension Debt)

Pension plans are designed to collect contributions from active workers, invest that money to produce a return, and use those combined contributions and investment returns to pay promised benefits. This design means that when a pension plan is working as it should, the fund will hold assets equal to the estimated value of the benefits it has promised to pay.

Unlike Social Security, which uses money from today’s workers to pay today’s retirees and does not invest assets, pension funds should receive money today that can be invested to achieve the total needed to pay retirement benefits in the future.

When the value of assets fall below the value of benefits promised, then a pension fund has “unfunded liabilities.”

- The liability is the promise to pay benefits; it is a formal financial term that indicates both a moral and legal obligation to pay a promised retirement benefit. The pension plan and the government that created the pension plan is obligated to pay the benefits it has promised, thus those promises are liabilities.

- And when a pension fund has a shortfall in assets, there is an unfunded liability.

For example, if a pension fund has promised $1 billion in benefits to current retirees and working teachers, for instance, it should have $1 billion in assets. If that pension fund only has $900 million in assets, it has $100 million shortfall. This is kind of like the pension funding formula becoming imbalanced. Below are some real examples of unfunded liability levels for state and local pension funds.

This shortfall in pension funding — the unfunded liabilities — is money that is owed to the pension fund by the relevant state or local government. Employers make 'amortization' payments into the pension fund that are regular, additional contributions made until there is no more funding shortfall. This is similar to making mortgage payments that pay off debt on a house. Thus, sometimes, people call unfunded liabilities “pension debt.”

To find out what the unfunded liability is for pension funds in your state, visit My State Fact Cards.

What is Normal Cost?

Normal cost is the contribution necessary, when added to investment income, to pay for benefits earned each year. The normal cost “prefunds” or “pays in advance” for promised pension benefits.

Normal cost is usually presented as a percentage of total salary earned by all teachers in the public pension system. This makes it easy to calculate the contribution rates for both members and their employers as a group.

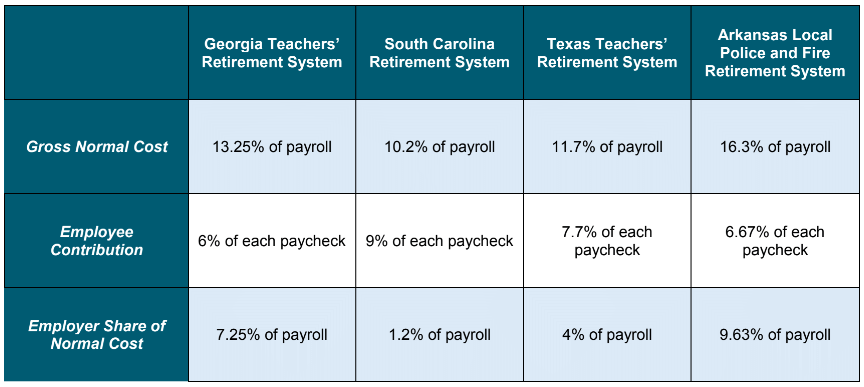

For example, suppose that when the actuaries got together to measure the payments necessary for your future pension, they determined 13.25% of your salary would be the appropriate amount—which is what Georgia’s actuaries estimate. Your state might require you to pay a portion of this—Georgia asks for 6%—while they would pick up the rest (in this case, 7.25%).

For example, suppose that when the actuaries got together to measure the payments necessary for your future pension, they determined 13.25% of your salary would be the appropriate amount—which is what Georgia’s actuaries estimate. Your state might require you to pay a portion of this—Georgia asks for 6%—while they would pick up the rest (in this case, 7.25%).

Typically, the amount of money taken out of each paycheck you receive for retirement benefits is the employee share of normal cost. Some pension systems also make payroll deductions for health care plans or retiree insurance plans.

In practice, the way that normal cost is paid for looks like this:

Example of How Normal Cost for Benefits Earned Each Year Gets Paid

Arkansas data is from fiscal year ending 2017. Georgia, South Carolina, And Texas figures are from fiscal year ending 2018, as reported by the state plans.

What is the Assumed Rate of Return?

Assumed rate of return is the single most important assumption that pension systems make to ensure they have enough funding to pay benefits promised.

To determine the amount of required contributions, a pension fund and its actuaries make educated guesses about how much they think they can earn by investing those contributions. That educated guess is called the assumed rate of return.

The higher the assumed rate of return, the fewer contributions teachers and their employers have to make. The lower it is, the higher contributions need to be in order to pay for the benefits promised.

How the Assumed Rate of Return is Determined

Pension boards typically meet with investment advisors, whose job is to suggest how money added to the fund from employees and taxpayers should be invested. This investment strategy is one way that a pension board plans for the future.

Any investment strategy has degrees of risk. Finance experts can estimate the probability of any given rate of return that portfolio of investments could produce. For example, an investment strategy of 50% stocks, 30% bonds, and 20% real estate might have a 1 in 2 chance of earning a 6% rate of return. That same portfolio might have just a 1 in 4 chance — 25% probability — of earning an 8% rate of return.

Most states direct pension boards to select a reasonable assumed rate of return on investments. Other states ask the state treasurer or other officials to get involved. A few states put the assumed rate of return directly into statute.

If the actual investment performance matches the assumed rate of return, then a pension fund is more likely to be healthy. If actual investment performance is less than assumed, then a pension fund might run into trouble. This is why it is important for pension funds to have reasonable assumptions.

A Few Common Misunderstandings

First, assumed rates of return aren’t historic averages. Analysts look at past performance to inform predictions, but the assumed rate of return is their best guess about the future.

For example, investment returns in the 1980s and 1990s were really strong. As a result, most pension funds have 40-year average investment returns of 8% or 9%. These historic averages are typically higher than the assumed rate of return that pension fund has used. But while the strong investment return is good, it is not a relevant data point for the pension board when they think about what the return rate should be for the future.

Second, assumed rates of return also do not determine benefits. Benefits are based on formulas that take into account years of service and compensation during the working years of public employees. Pension systems specialists, actuaries, start by estimating the total amount of benefits and then calculate the contribution rate needed to pay them, factoring in an assumed rate of return.

If investment returns are strong, that does not directly cause base pension benefits to increase. And if investment returns are weak, that does not mean pensioners will see their monthly checks cut. Some states have linked cost-of-living adjustments to pension fund investment performance, so retirees might get higher checks when investments are strong. But this is a supplemental benefit, core pension benefits will not be cut if investments underperform. Other states have created variable pension benefits where there is a minimum amount, and the actual payment fluctuates based on market performance. But again, the base benefit these retirees received as a minimum starting point was based on the benefit formula, not investment returns during their working years.

To find out if your retirement plan will provide adequate income, look up your plan’s interactive scorecard in the Retirement Security Report

Understanding The Pension Funding Formula

How does a state, or the fund administering pension benefits, make sure it will be able to pay promised retirement income to public workers when they retire?

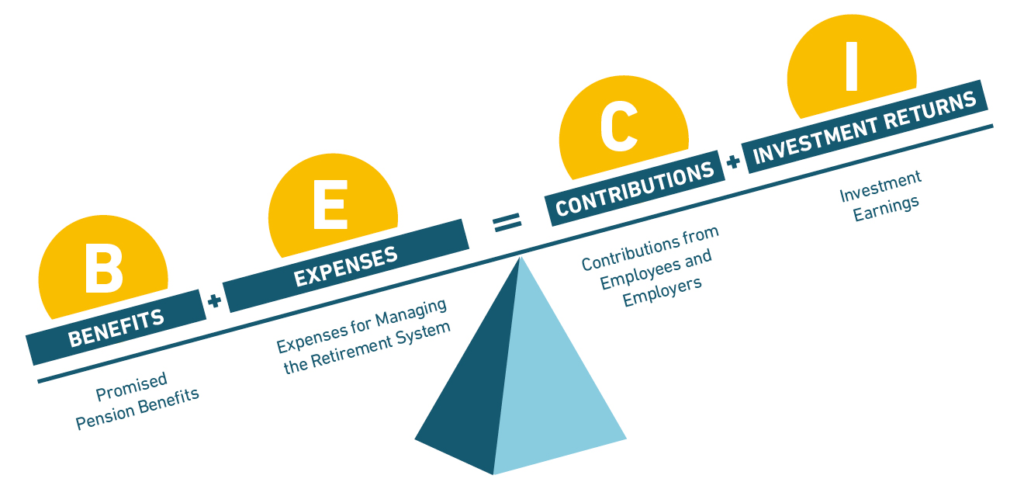

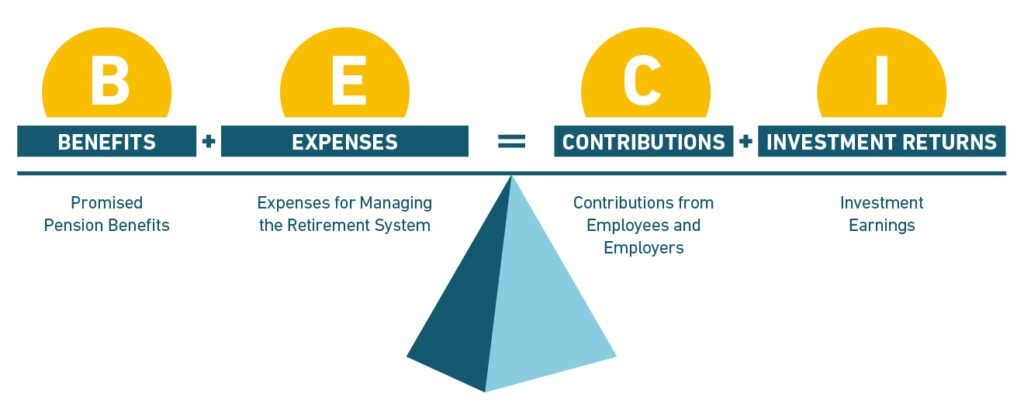

The answer can be boiled down into a simple idea: retirement systems work to make sure that contributions into the pension fund, plus investment returns on that money, match the value of benefits promised to public workers, plus expenses to run the pension plan in the first place. This is known as B + E = C + I, and it looks like this:

How Pension Benefits are Funded

Source: Equable

Funding a pension plan using this formula can be broken down into three basic steps.

Step 1 is estimating the value of all benefits earned. Actuaries look at the benefits offered by the pension plan, the rules for vesting, and qualifications for claiming a retirement benefit. They make educated guesses about what salaries public workers will earn, when they will retire, and how long they will live. Using this information, actuaries then estimate how much retirement income a pension system will need to pay out each year in the future, and what the value of all those promised payments are worth today.

Put simply: actuaries take a guess at how many pension checks are going to be paid out in the future, what the value of those checks will be, and then count them all up and figure out what that money is worth in current dollars. The result is the value of Benefits, and it is the first major component

Of course, there are costs in running a pension fund that are separate from the benefits it’s obligated to pay out. Salaries for staff, money to process checks, resources to build tools that workers can use to manage their future retirement. Expenses are usually a very small amount relative to assets the fund manages, and these are easily added to the cost of benefits.

Step 2 in funding a pension plan is getting money into the pension fund. Contributions are the amount of money paid into a pension fund from public workers, employers (such as school districts, police departments, or municipal agencies), and other government sources (such as the general state budget). Actuaries make an assumption about how much these contributions will grow once they are invested. Using this assumed rate of return, actuaries can determine how much should be contributed in a given year to pay in advance for all of the benefits earned in that year.

The more investment returns that actuaries think will be earned, the lower the amount of needed contributions into the fund today. The lower the assumed investment returns, the more contributions will be needed today. Whatever the assumptions, though, some amount of Contributions need to flow into the pension fund.

Step 3 is simply earning Investment Returns. Once a contribution rate is set and that money is flowing into the pension fund, it is up to the pension board and investment managers to make sure that actual rates of return are at least as good as expectations.

When everything is working, the value of Benefits plus Expenses will be matched by the appropriate amount of Contributions plus Investment Returns. If any of these elements is out of balance, the pension system could be underfunded. If actuaries don’t accurately estimate the size of benefits, then contributions and investments won’t be enough to cover them. If states don’t make appropriate contributions, or investment returns don’t perform as expected, funds could run short.

How Does Vesting Work?

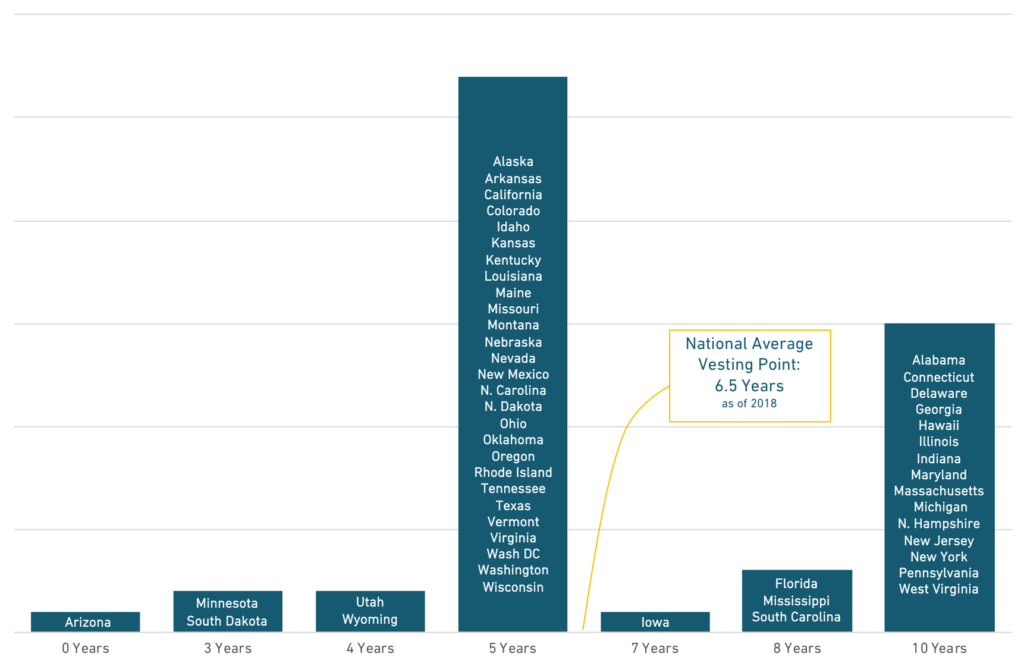

If you’re like most public workers, you probably have to work five to seven years before you can qualify for any pension benefits — reaching this threshold is known as vesting.

Before vesting, no pension benefits have been guaranteed. If individuals enrolled in a pension plan leave employment before vesting, they are only entitled to receive back their own contributions.[1] The number of years required vest is the minimum necessary to qualify for claiming a future retirement benefit. Qualifications to claim a pension are usually a combination of years of service and age. For example, a common qualification threshold is 60 years old and at least 10 years of service. Another common qualification is “Rule of 90,” where the threshold to cross is any combination of age and years of service that add up to 90, such as 65 years old with 25 years of service.

Changing Vesting Periods

One way that states have changed public sector pension plans over the past few decades has been to increase the number of years required to vest. For example, in 2008 the average vesting period for pension plans covering teachers was 5.8 years. But over the past 10 years more than a dozen states have increased the pension vesting period. Today, the average vesting point is 6.5 years. As shown in the chart below, in 20 states teachers must now wait seven to 10 years to vest.

Source: Equable Institute and Lifting the Pension Fog

Some argue that longer vesting periods help retain teachers—though there isn’t strong research to back up this claim.[2] The reality is that longer vesting periods mean fewer teachers will receive pension benefits.

[1] The exception to this rule is South Dakota Retirement System, which will refund to a non-vested member upon leaving employment 100% of employee contributions and 75% of employer contributions on their behalf. SDRS is very rare in offering this kind of pension benefit.

[2] There is only limited empirical research on the effects of vesting periods. While it is possible that longer vesting periods might keep teachers who have spent four years in the workforce another year to reach a fifth year if vesting is at five years, teacher exit surveys suggest life events (such as having a child or a change in a spouse’s job), changes in job preferences, and school leadership are driving factors in causing teachers to leave their jobs — none of which will be influenced by a vesting period. See this report from Bellwether, 2018.

How Pension Benefits Are Calculated

Pension benefits are typically a fixed monthly payment in retirement that is guaranteed for life. Some pension benefits grow with inflation. Other pension benefits can be passed on to a spouse or dependent. But pensions aren’t the only financial route to guaranteed lifetime income after you retire.

What makes pensions unique is that the retirement income benefit is determined by a formula that does not take into account the amount of money actually saved. In other words, the amount of the pension stays the same even if the retirement system isn’t keeping up with saving money to pay the benefit.

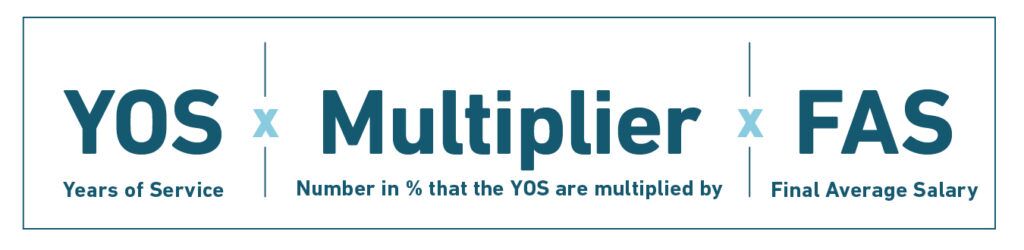

Here is how the formula typically works:

In the formula “years of service” is how many qualifying years a public worker has worked for their employer within the pension plan.

“Final average salary” is defined slightly differently from state to state, but always is a reference to the compensation amount that a pension will be based on. In most states, a final average salary — also called final average compensation — is the average of the last five years of work, or the last three years. Other states use the three or five highest years of salary, rather than the years at the end of your career.

The “multiplier” in the formula is used to determine the percentage of final average salary that will be received as a retirement benefit. Years of service are multiplied using this specific number. That amount becomes a percentage of final average salary. And the result equals the amount ultimately received as a benefit in retirement. The higher the multiplier, the larger the benefit. Multipliers are sometimes known by other terms, such as “accrual rate” or “crediting rate” but they mean the same thing.

A typical multiplier is 2%. So, if you work 30 years, and your final average salary is $75,000, then your pension would be 30 x 2% x $75,000 = $45,000 a year. That $45,000 becomes your guaranteed lifetime income.

Note: Your years of service times the multiplier (in this case, 30 x 2% = 60%) is known as your “replacement rate,” or the percentage of your final average salary that you’ll ultimately receive.

To find out if your retirement plan will provide adequate income, look up your plan’s interactive scorecard in the Retirement Security Report