There are many unknowns in the Age of COVID-19, but fortunately when it comes to forecasting what is likely to happen to public pension funds over the coming decade, we have a guide: what happened after the Great Recession. Here’s are the seven trends we expect to see in public pension funding in the COVID-19 era:

1. States will try to reduce contributions to public pension funds

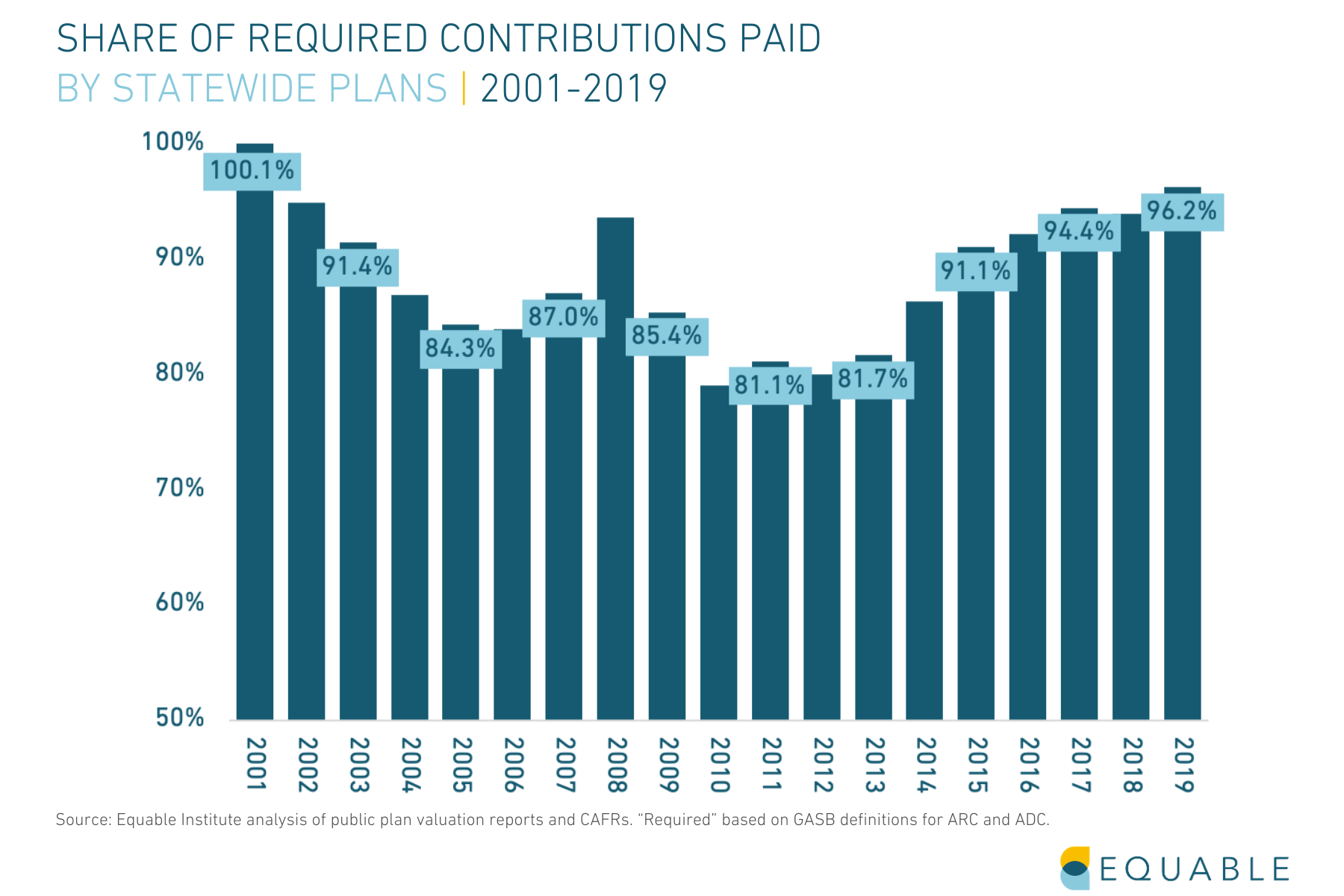

We should expect that states will try to reduce their pension contribution levels. Between 2008 and 2010 there was a drop off in the percentage of required contributions that was actually paid by state governments, from around 93% to 79% of actuarially determined employer contributions. This shift away from a commitment to full funding was driven by low tax revenues and budget constraints — which state and local governments are going to be feeling for several years to come. It wasn’t until five years after the Great Recession ended (in 2013 and 2014) that states began to improve their funding practices.

2. States will reduce their investment assumptions

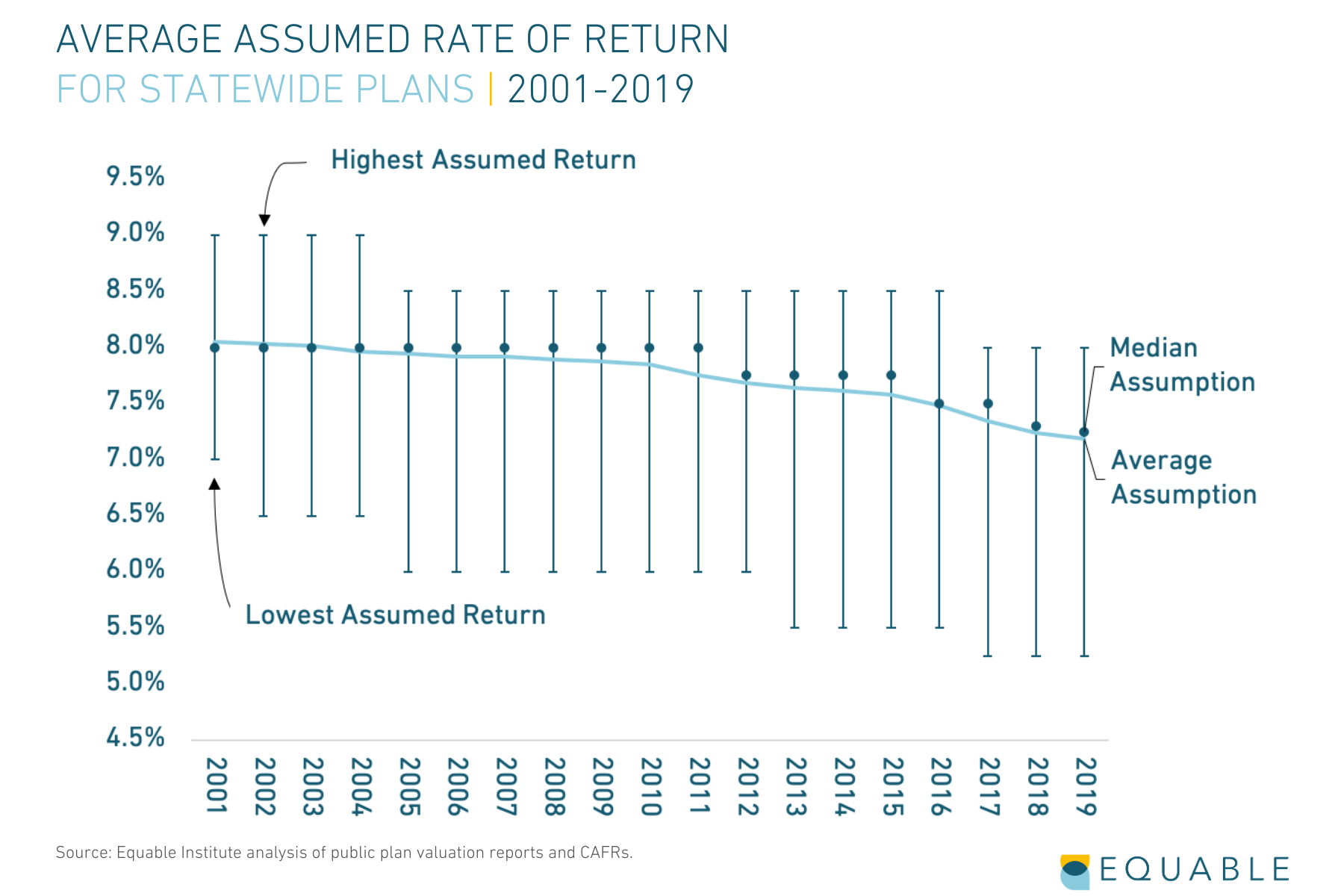

States reduced their assumed rates of return after the Great Recession, but only gradually at first. The first steps were from the 8% average in 2008 down toward 7.75%, but around three to four years after the end of the Great Recession a handful of states started making meaningful reductions. The average and median assumed return in 2016 — seven years after the Great Recession ended — was still only down to 7.5%.

3. Employer contributions to public pension funds will grow

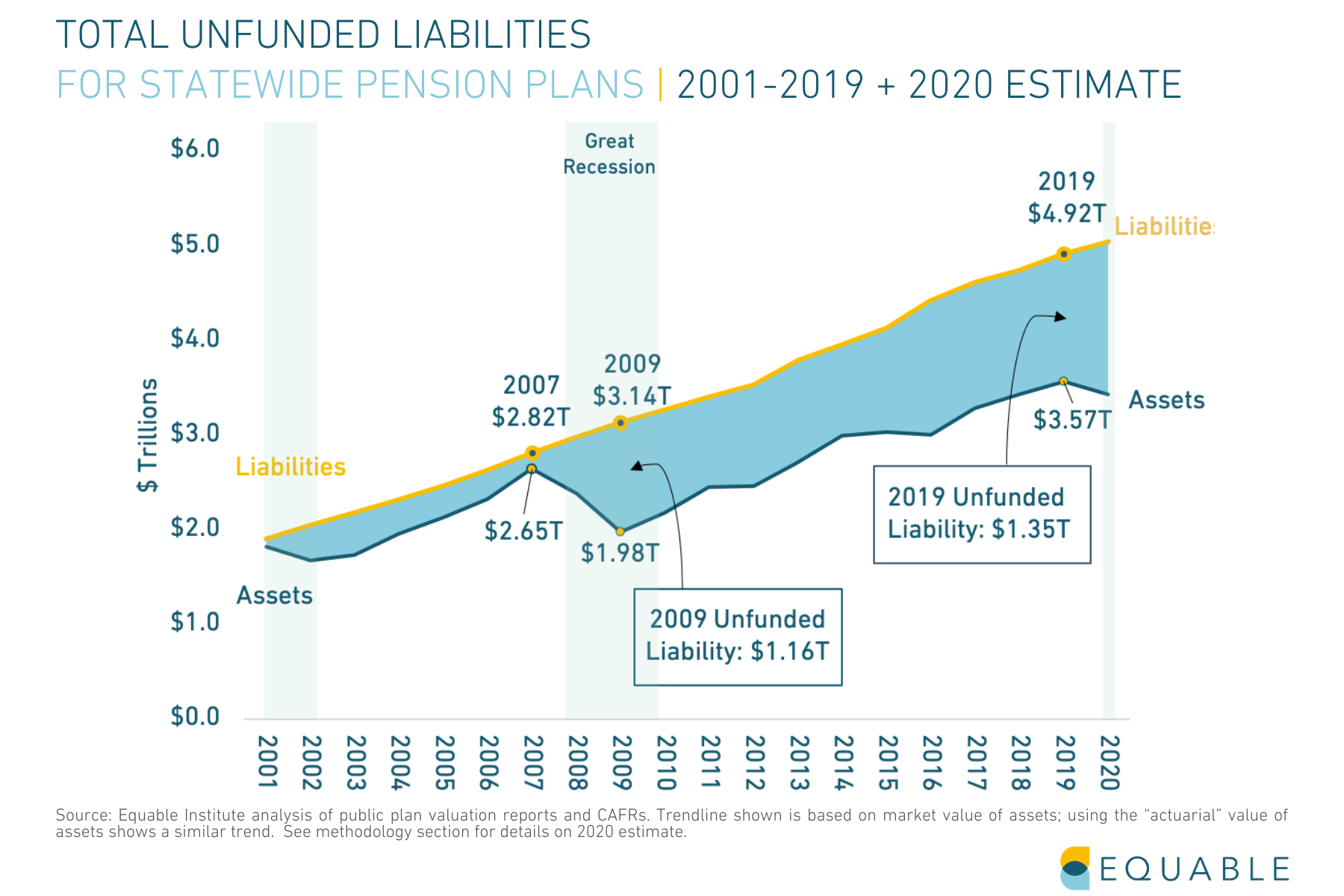

Unfunded liabilities spiked because of losses during the Financial Crisis, growing steadily in the decade that followed. And this led to employer contributions doubling over 10 years, as a percentage of payroll. Fortunately, financial market losses so far have not been as severe as they were in 2008 and 2009. Unfortunately, statewide pension funds entered the COVID-19 Recession with more than seven times the unfunded liabilities ($1.35 trillion as of 2019) as they did entering the Great Recession ($175 billion as of 2007). At a minimum, investment returns are going to underperform the assumed return for this year, which will add to unfunded liabilities. And we can expect required employer contribution rates will continue growing in the coming years.

4. Some states will improve the funded status of their public pension plans, but many others will stagnate.

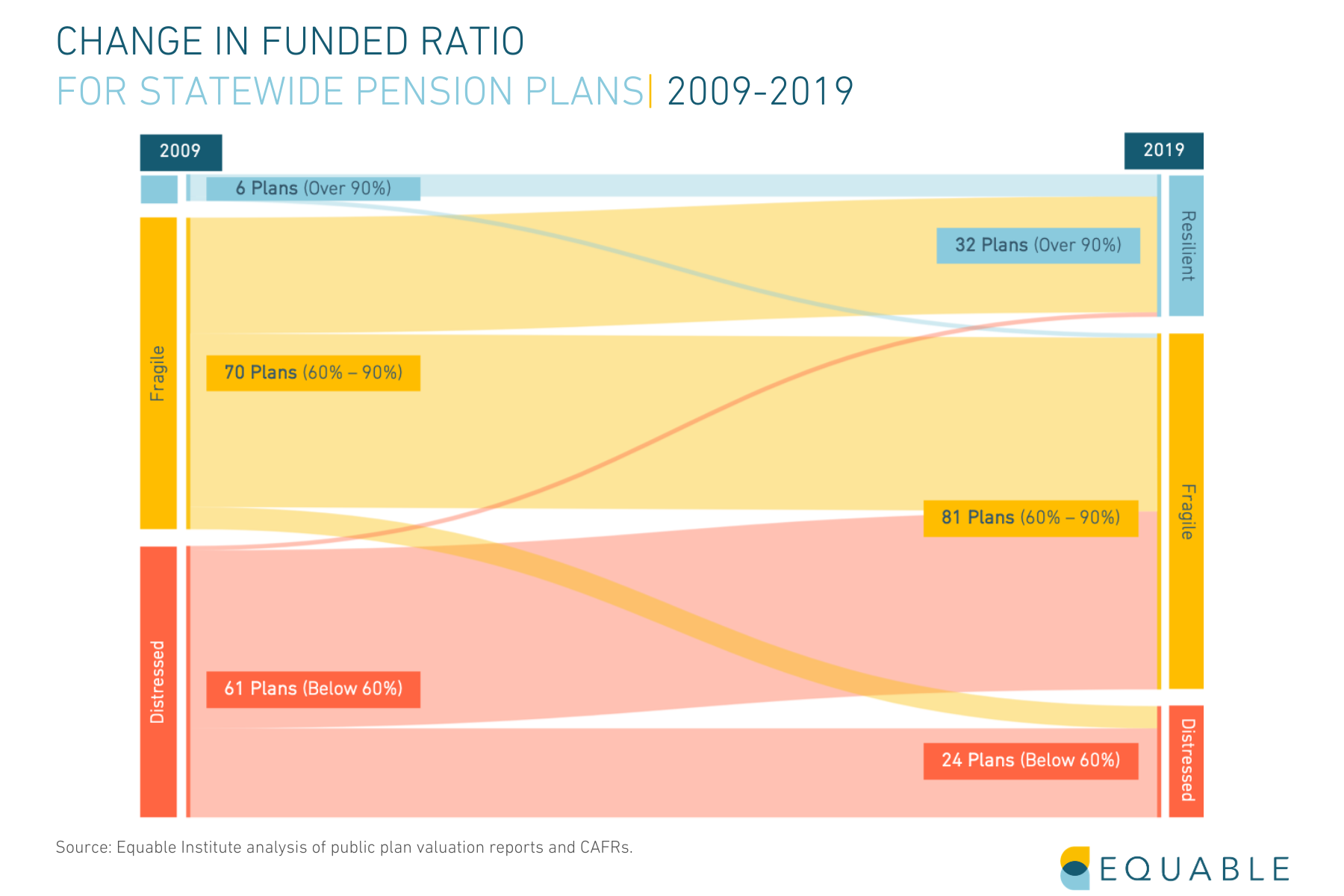

There was a divergence amongst statewide pension plans after the Great Recession. At the end of 2009 there were 70 plans with a funded ratio between 60% and 90%. By 2019, roughly one-third (27) of these plans had improved to over 90% funded, about half (38) stagnated in this category range, and five others dropped below 60% funded. Essentially, while a handful of statewide plans were able to recover from the Great Recession, as a whole the funded status of public pension funds stagnated at around the 70% funded level between 2011 and 2019.

We might expect that in the coming years we’ll see a drop in the funded status of public pension funds for the years 2020 and 2021, and a divergence in which plans are able to recover. But without active steps to learn from the decade following the Great Recession, the funded status of statewide retirement systems will stagnate again. And remaining perpetually underfunded will contribute to ever growing costs.

5. Employee contributions to public pension plans will likely rise.

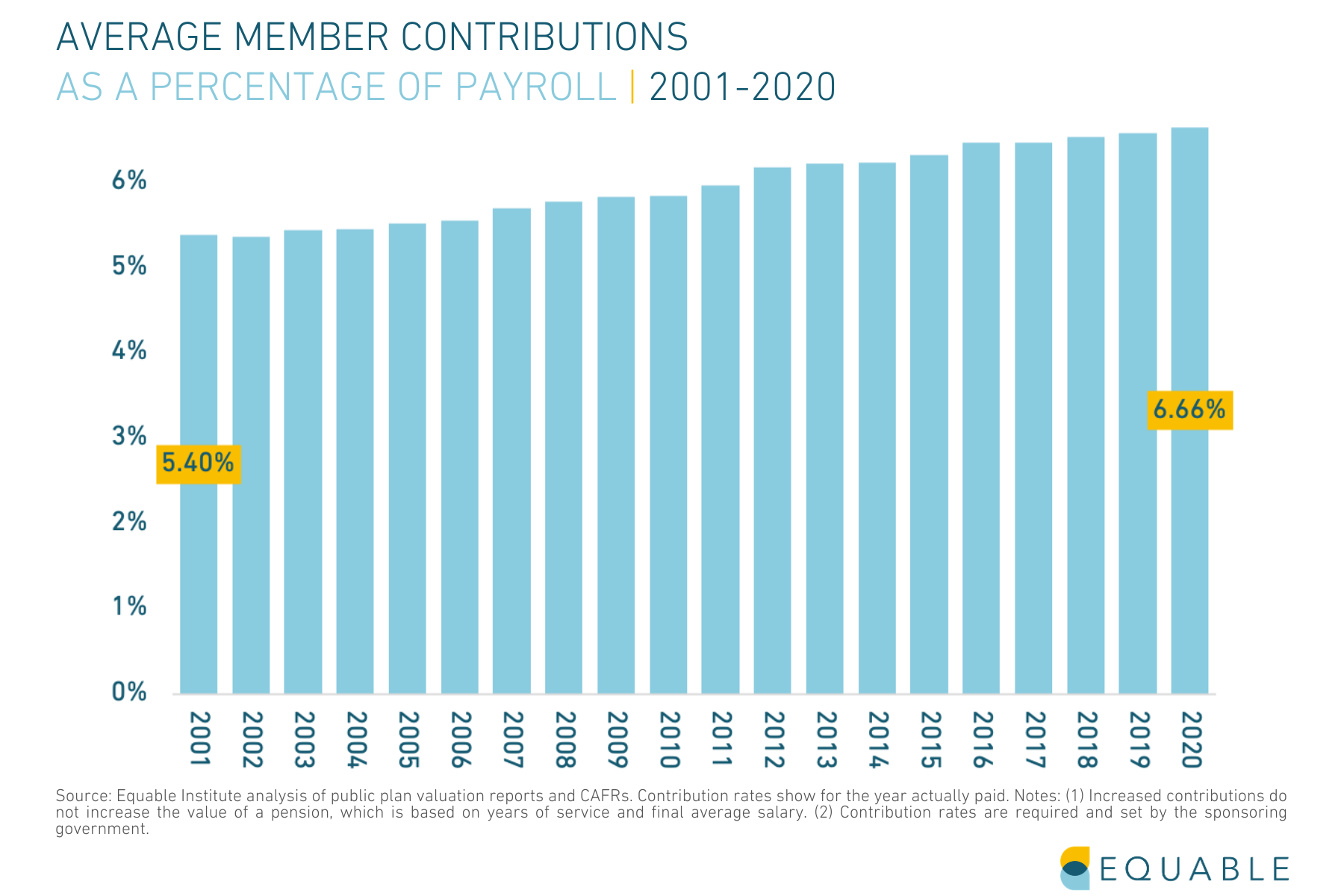

Those growing costs over the next few years are likely to be partially carried by public employees. States gradually turned to member contributions to pay for increasing costs following the Great Recession. By 2015, employees were paying over 0.75% more from their paychecks for the same (or lessor) benefits.

6. Some states may seek to reduce public pension benefits to reduce costs.

States also pursued various changes to benefits that would reduce their long-term costs, including the reduction or elimination of cost-of-living adjustments. Sometimes these changes were for new members, other times (where legal) they were for active employees and/or retirees. It is highly probable that states will seek similar ways to reduce their costs, but in some states they’ve already cut back as much as legally possible.

7. Some states may shift public pensions investments into riskier asset classes or lean into a more conservative strategy.

We also know that states increased their asset allocations to higher risk, higher reward investments in the years following the Great Recession. In some ways this diversification likely helped pension funds avoid being too exposed to the sharp decline in U.S. equities in March 2020. In other ways this shift meant state pension funds didn’t fully capture the returns from the bull market between mid-2009 and the end of 2019. Going into the COVID-19 Recession, states had allocated more than 19% of their portfolios to private equity, real estate, hedge funds, and other alternative investments. Pension funds might seek to expand these investments in a search for yield in the coming years, but they might also not be as lucrative a set of asset classes in a COVID-19 beset economy.