How does a state, or the fund administering pension benefits, make sure it will be able to pay promised retirement income to public workers when they retire?

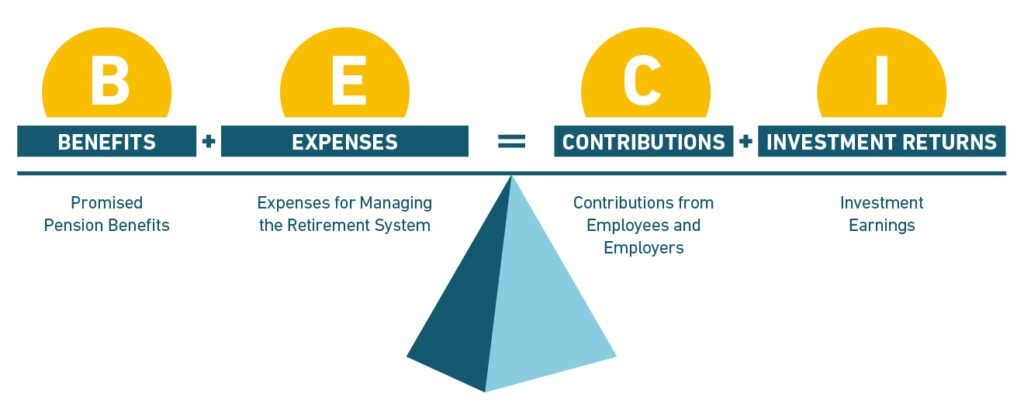

The answer can be boiled down into a simple idea: retirement systems work to make sure that contributions into the pension fund, plus investment returns on that money, match the value of benefits promised to public workers, plus expenses to run the pension plan in the first place. This is known as B + E = C + I, and it looks like this:

How Pension Benefits are Funded

Source: Equable

Funding a pension plan using this formula can be broken down into three basic steps.

Step 1 is estimating the value of all benefits earned. Actuaries look at the benefits offered by the pension plan, the rules for vesting, and qualifications for claiming a retirement benefit. They make educated guesses about what salaries public workers will earn, when they will retire, and how long they will live. Using this information, actuaries then estimate how much retirement income a pension system will need to pay out each year in the future, and what the value of all those promised payments are worth today.

Put simply: actuaries take a guess at how many pension checks are going to be paid out in the future, what the value of those checks will be, and then count them all up and figure out what that money is worth in current dollars. The result is the value of Benefits, and it is the first major component

Of course, there are costs in running a pension fund that are separate from the benefits it’s obligated to pay out. Salaries for staff, money to process checks, resources to build tools that workers can use to manage their future retirement. Expenses are usually a very small amount relative to assets the fund manages, and these are easily added to the cost of benefits.

Step 2 in funding a pension plan is getting money into the pension fund. Contributions are the amount of money paid into a pension fund from public workers, employers (such as school districts, police departments, or municipal agencies), and other government sources (such as the general state budget). Actuaries make an assumption about how much these contributions will grow once they are invested. Using this assumed rate of return, actuaries can determine how much should be contributed in a given year to pay in advance for all of the benefits earned in that year.

The more investment returns that actuaries think will be earned, the lower the amount of needed contributions into the fund today. The lower the assumed investment returns, the more contributions will be needed today. Whatever the assumptions, though, some amount of Contributions need to flow into the pension fund.

Step 3 is simply earning Investment Returns. Once a contribution rate is set and that money is flowing into the pension fund, it is up to the pension board and investment managers to make sure that actual rates of return are at least as good as expectations.

When everything is working, the value of Benefits plus Expenses will be matched by the appropriate amount of Contributions plus Investment Returns. If any of these elements is out of balance, the pension system could be underfunded. If actuaries don’t accurately estimate the size of benefits, then contributions and investments won’t be enough to cover them. If states don’t make appropriate contributions, or investment returns don’t perform as expected, funds could run short.

This article is part of Equable’s Pension Basics series. To learn more about how your pension works, check out the other articles in the series:

1. How Pension Benefits Are Calculated

2. Vesting

3. The Pension Funding Formula

5. Normal Cost

6. Unfunded Liabilities (aka Pension Debt)

7. Actuarially Determined Contributions

10. Governance

11. Pension Myths & Facts: The Assumed Rate of Return Does Not Determine the Value of Benefits

12. Pension Myths & Facts: The Funded Status of Pension Plans Does Not Depend on More Public Employees