In 2023, U.S. public pension funds remain fragile.

According to Equable Institute’s State of Pensions 2023 report, state and municipal retirement systems are on track to miss their investment targets and are unlikely to see meaningful improvements in their unfunded liabilities or funded ratio in 2023.

In this post, we will look at pension funding trends and detail the health of pension funds in an increasingly unpredictable market and where risky investments are more popular than ever. We will also highlight the core reasons why pension funds are still struggling to keep up after the record investment gains of the Covid-19 era.

This article features content from State of Pensions 2023

Read the Full Report

Download the Fact Sheet

The State of Pensions in 2023: Public Pension Debt has Flatlined

What is the pension funding gap in 2023?

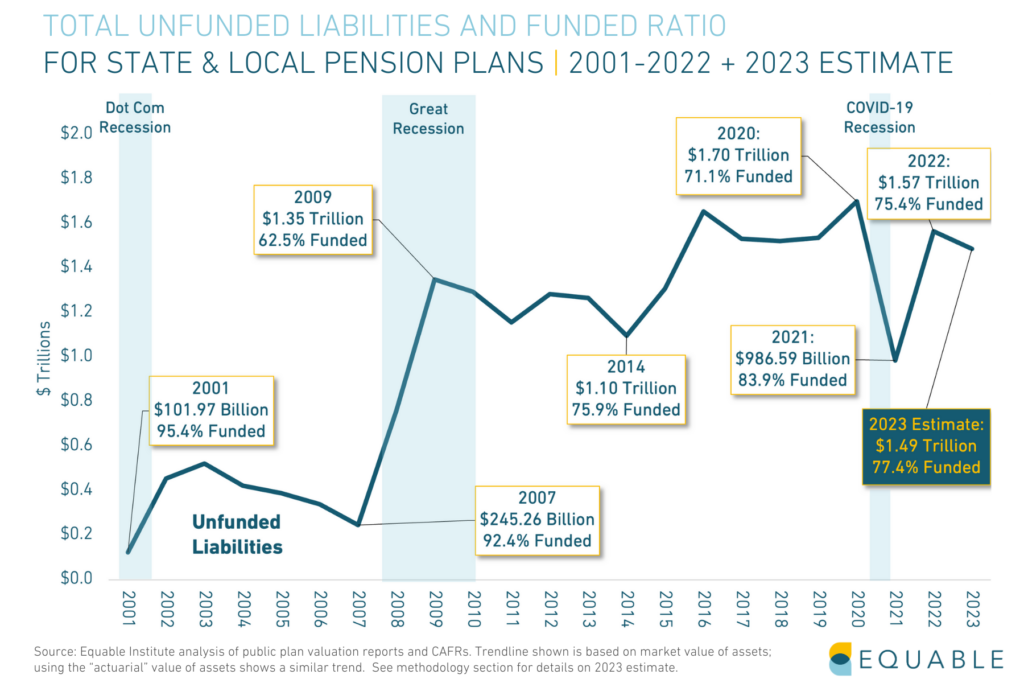

The national pension funding shortfall (or pension debt) for statewide retirement systems was $1.57 trillion at the end of 2022, per Equable Institute’s State of Pensions 2023 report. We estimate that 2023 unfunded liabilities will remain effectively flat, decreasing slightly to $1.49 trillion.

The funding shortfall is the gap between money held by pension funds and the value of all future benefits it has promised to pay. This is formally called "unfunded liabilities" and is also sometimes called pension debt.

The shortfall was, in part, caused by investment volatility set off by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, there has been relatively little change in the national shortfall in assets for state and local pension plans since the Financial Crisis. Unfunded liabilities decreased to their lowest level in 2021, but since then have reverted to just a slight improvement from pre-Covid 19 pandemic levels.

Preliminary 2023 investment returns for state and local plans are 5.3% on average. Federal Reserve policy to address inflation ended an era of easy money, which translated into a bear market for public equities and reduced valuations, known as markdowns, for private equity and real estate.

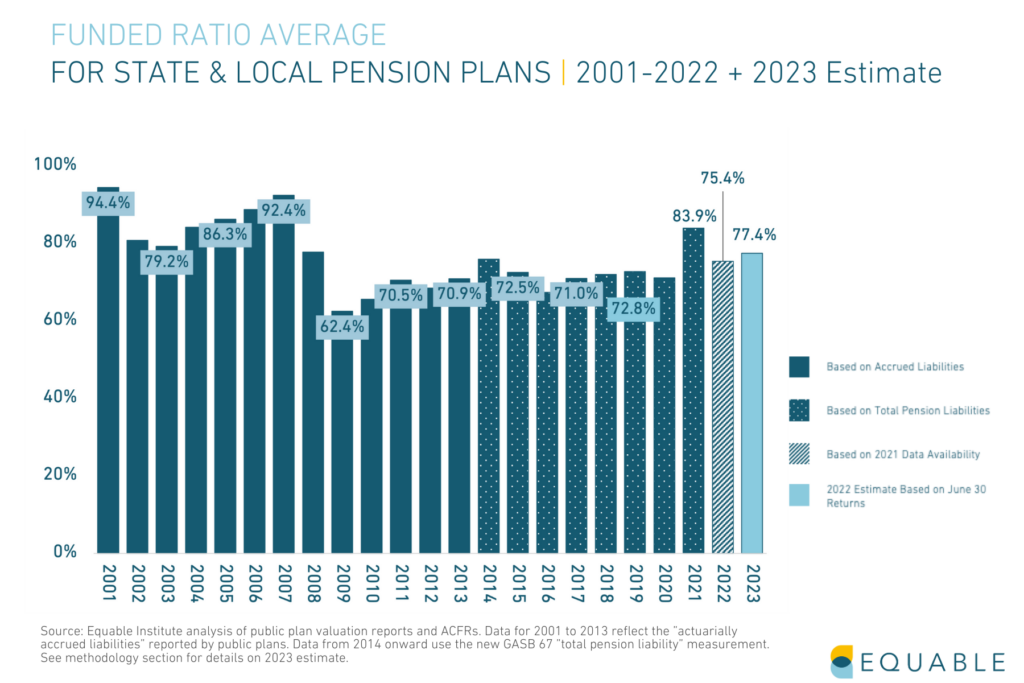

On average, American public pensions plans currently hold 77.4% of assets needed to pay future retirees their pension benefits. This is a positive improvement over the 72.8% pre-Covid funded ratio in 2019. But, it is still much lower than the 83.9% funded ratio in 2021. More importantly, it's dramatically lower than the pre-Great Recession funded ratios of 2007 and 2008.

In contrast, retirement systems in the U.S. had 92.4% of the money promised to public retirees in 2007, before the Great Recession. Losses because of the Financial Crisis of 2008 knocked this funded ratio down to 62.4% by 2009.

Pension funds have been able to recoup some of the losses experienced during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. But, they still have not recovered from the 2008 recession. And capital market forecasts are warning future returns are likely to be muted.

To maintain the positive trends in pension funding, states will need to adopt safer practices. This includes establishing realistic assumed rates of return and appropriately managing the risk level of their investments.

Public Pensions in 2023: Why the Assumed Rate of Return Matters

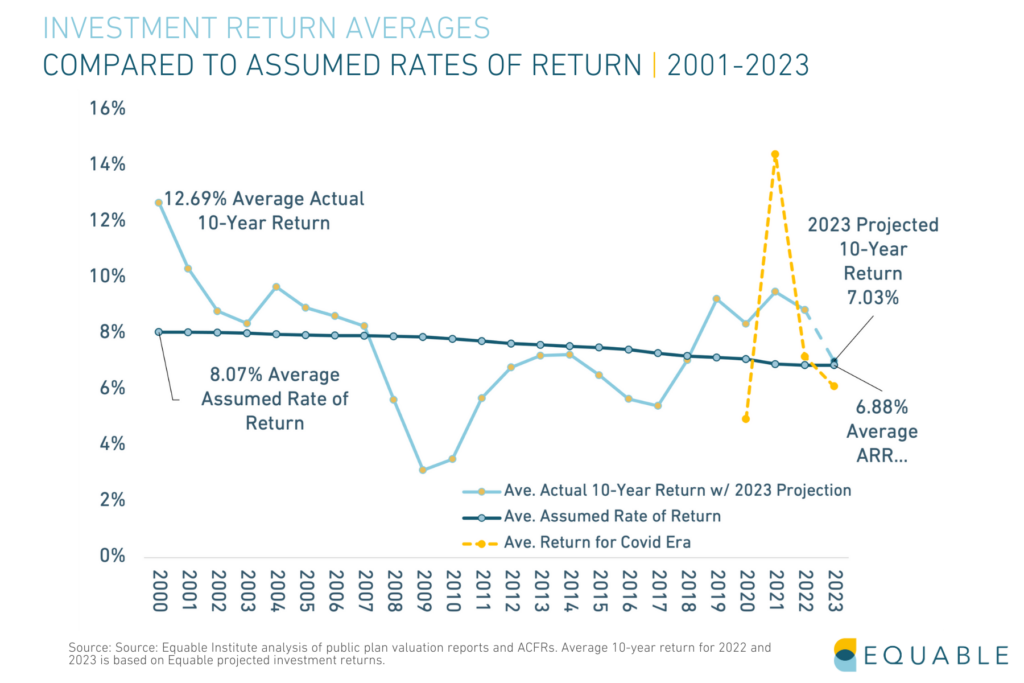

There is a significant gap between projected earnings and fiscal reality for public pension plans in many states. This gap has persisted for several years.

Still, the assumed rates of return used by many retirement systems have remained significantly higher than actual investment earnings. However, many states have meaningfully reduced their assumed rates of return in response to economic shifts. The average assumed rate of return is now 6.88% in 2023—down from 8.05% in 2001.

We estimate 2023 investment returns for U.S. public pension funds will average 5.3% (based on data through June 30).

This is significantly lower than the 6.88% average assumed rate of return. For the first time, however, the average 10-year investment return has fallen to around the assumed rate of return. This indicates a dampened outlook for investment returns long-term.

The average investment return for the Covid era (2020-2023) is 6.15%, which is below average investment assumptions. Despite record investment returns in 2021, the Covid era has not proven to be overly beneficial for pension funds.

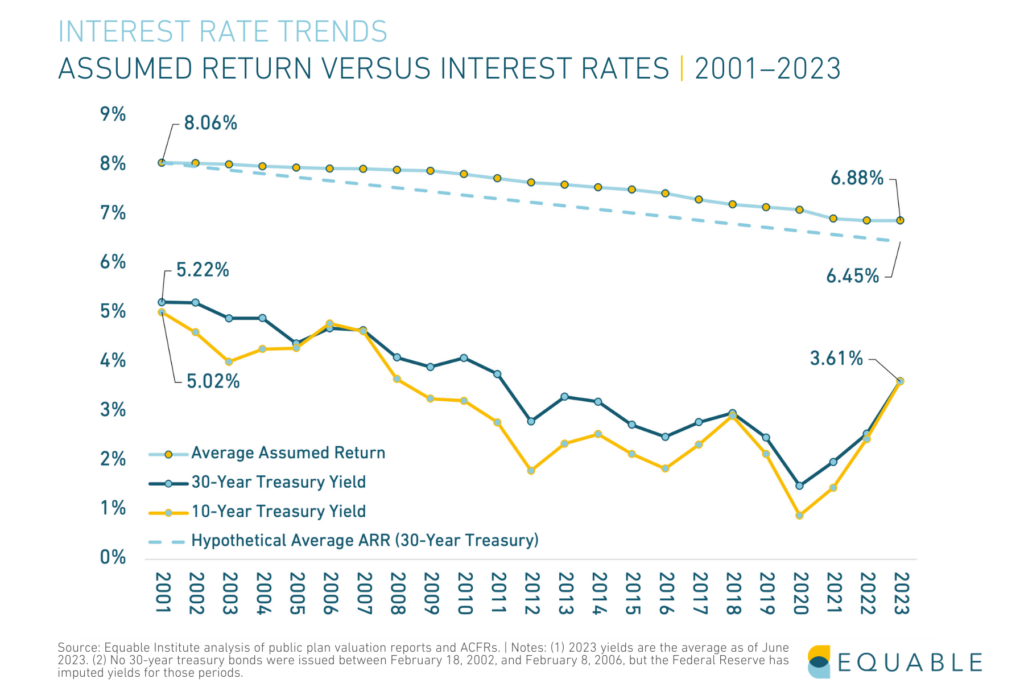

Interest rates are considered an indicator of future market performance. States and pension boards have been slow to reduce their assumed rates of return, relative to declining interest rates. Even factoring in recent interest rate increases, the gap between interest rates and assumed rates of return reflects an increased amount of risk that pension funds are accepting relative to two or three decades ago.

Pension fund assumed rates of return have not kept pace with rapidly declining interest rates over the last two decades. Many funds are over-estimating what their investments will earn. Others are making a lot of high risk, high reward investments to try and hit their optimistic targets. Some funds are doing both.

The chart below shows the recent trend in assumed rates of return in tandem with interest rates.

If assumed returns had kept pace with declining interest rates since 2001, the average assumed rate of return for 2023 would have been around 6.45%, not the 6.88% plans currently average.

The optimistic assumed rate of return used by most pension funds to make financial decisions may be increasingly hard to achieve if America’s economic future remains uncertain.

Pension Funding in 2023: How does national pension debt affect public workers?

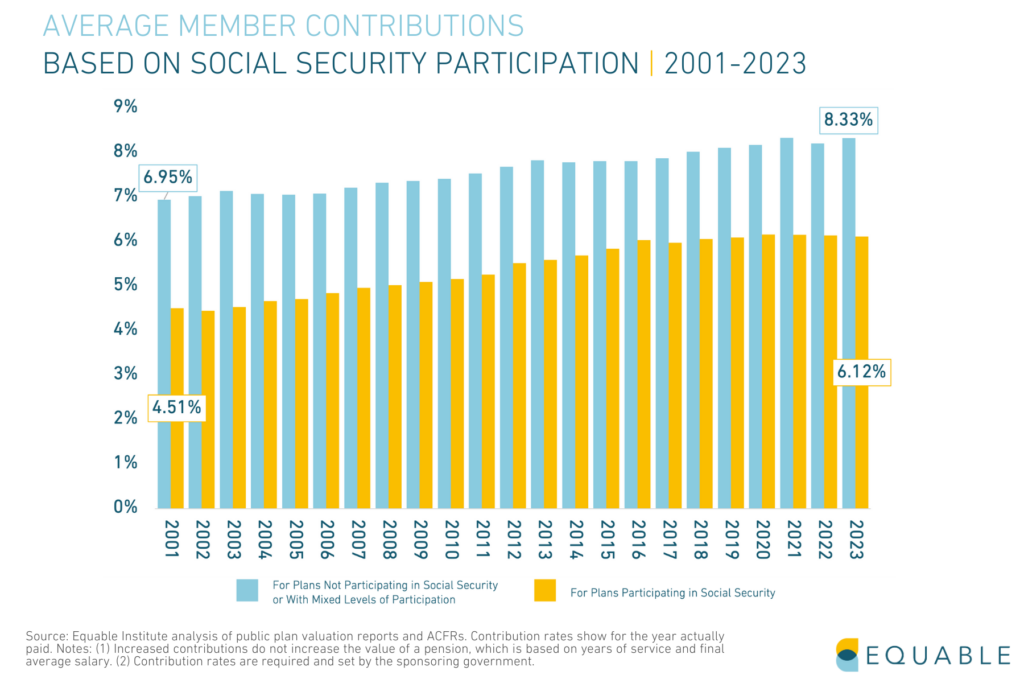

The pension debt carried by governments is costly to pay down and creates pressure on the public budget. It may cause an increase in required pension contributions for public employees or benefit reduction like the elimination of cost-of-living (COLA) adjustments for retirees, which in an era of record inflation is increasingly important. Higher employee contribution rates means less money in public workers' paychecks. In recent years, the first number has been growing while the latter shrinks.

In 2023, average member contribution rates reached an all-time high. Public sector workers who are enrolled in Social Security are paying 35.7% more than they did in 2001. Workers who are not enrolled in social security are paying 19.9% more than they did in 2001.

In times of economic hardship, higher contribution rates for governments may have other impacts. They may result in higher property taxes, delayed raises, cuts in school funding, or reductions in essential services.

Pension Trend to Watch in 2023 and Beyond: Public Pension Plans Are Addicted to Risk

How are pension plans investing their assets?

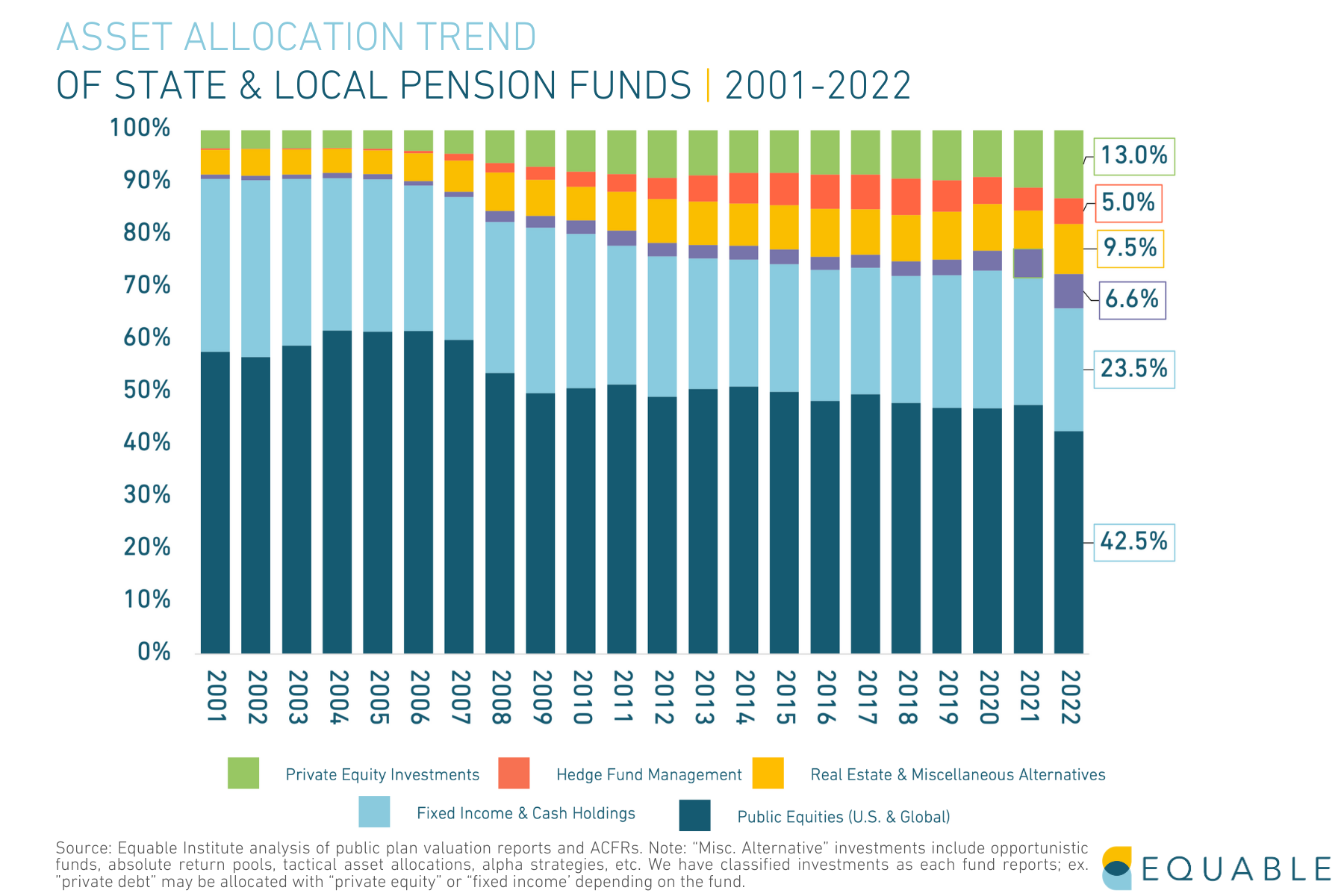

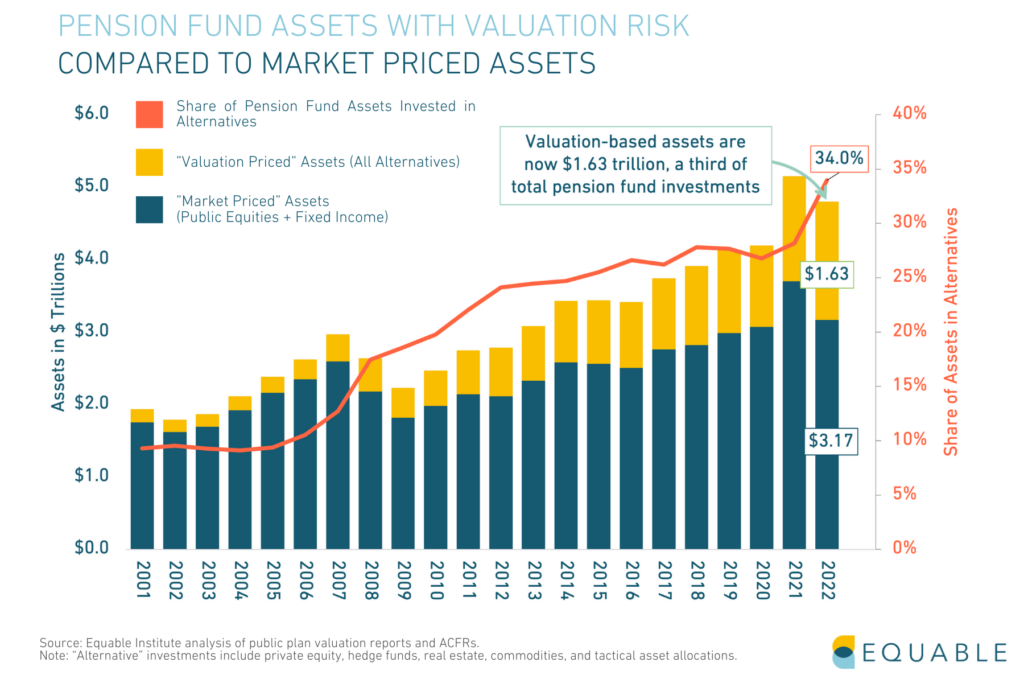

States are trying to make up for negative pension funding trends like lower projected returns on stocks and bonds. They are utilizing more and more alternative investments to chase higher returns. This includes investments hedge funds and private equity strategies, as well as real estate.

Since 2001, pension funds invested a higher percentage of their assets into these alternative investment categories. Hedge funds, real estate, and private equities are known for a lack of transparency. They also tend to be more volatile in times of economic uncertainty.

In 2023, “Alternatives” comprise a third of pension fund investments (34.0%), the largest share in history. Notably, private equity jumped to 13.0% of allocations.

Ultimately, state pension funds are in competition with each other when vying for these deals and market strategies. Statistically speaking, there are going to be plans that lose out on this work. Unless state pension funds have better success than the market, it is likely that the net average result across all plans will be modest at best. At worst, these strategies will perform worse than traditional passive equity investment strategies.

Public Pension Funds are Vulnerable to “Valuation Risk”

Public pension funds now face an emerging concern: “valuation risk.” While traditional investments like stocks and bonds are based on prices set by the market, alternative assets are not.

The majority of alternative investments via private equity and real estate use valuation models to get priced or for when they sell. There is very little transparency when it comes to these models. They are not updated in real time the way market prices are, so it is almost impossible to prove if the value of these assets are accurate or “fair.”

This means that a large and growing share of pension fund investments might not be correctly valued. If that’s the case, many states may not be making large enough contributions to their pension funds to ensure their stable funding. And, if the value of those assets get marked down, states could see significant declines to their funded ratio. This is valuation risk.

As of 2022, $1.6 trillion of public pension fund assets have exposed themselves to valuation risk. This comprises 34% of pension funds’ investments.

However, not all states expose themselves to the same level of valuation risk. The interactive map below shows what percentage of each state’s investments are in alternative assets.

The State of Pensions 2023: Most Public Pension Systems Are Still Financially Fragile or Distressed

What do pension funding gaps mean for states?

Despite an improvement over 2022’s -5.94% investment returns, 2023 is unlikely to yield meaningful improvement for most states’ funded status.

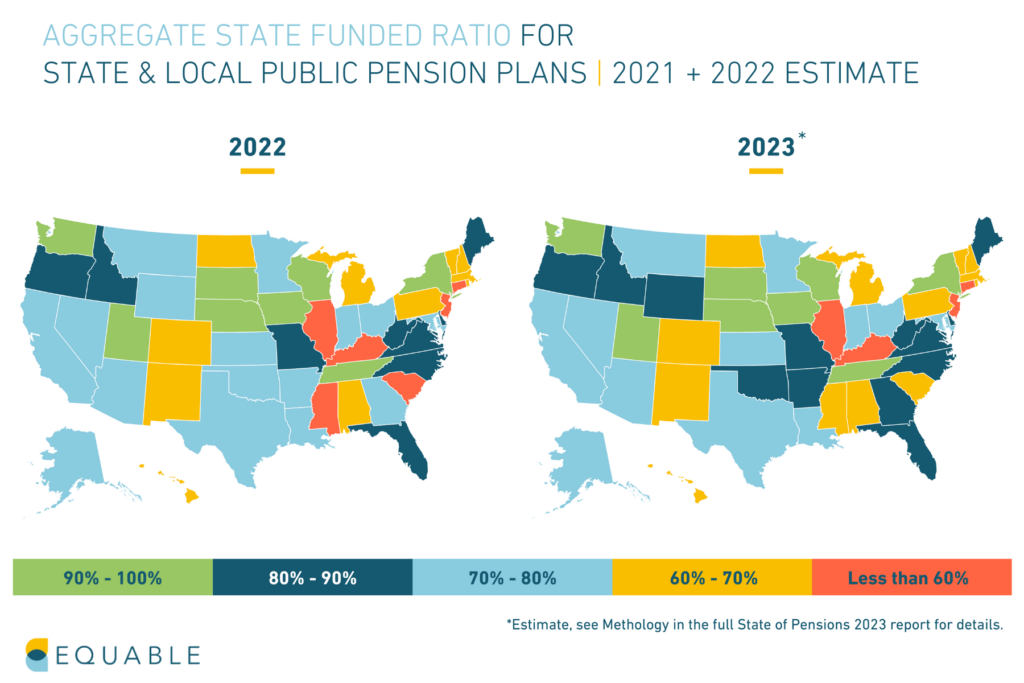

Most states are going to have flat funded status from 2022 to 2023: only 7 states changed color on the map from 2022 below. Out of the 225 plans in Equable’s analysis, 46 plans will have a lower funded ratio in 2023 than the previous year.

Currently, 59% of all statewide plans are "fragile" and more than 16% of plans are "distressed" as of 2023. These plans face an uphill climb to recovery due to sharp losses in 2022, despite strong returns in 2021.

Fragile status generally means a retirement plan is between 60% and 90% funded. While they’re not at immediate risk of insolvency, they are accumulating unfunded liabilities. Over time, that will gradually become a strain on budgets and government revenues. One or two asset shocks could send the plan into a downward spiral.

Today, only 25% of state and local pension plans are economically resilient, according to the Equable Institute report. This means the plans hold assets that cover 90% or more of promised public employee pension benefits for at least a few consistent years.

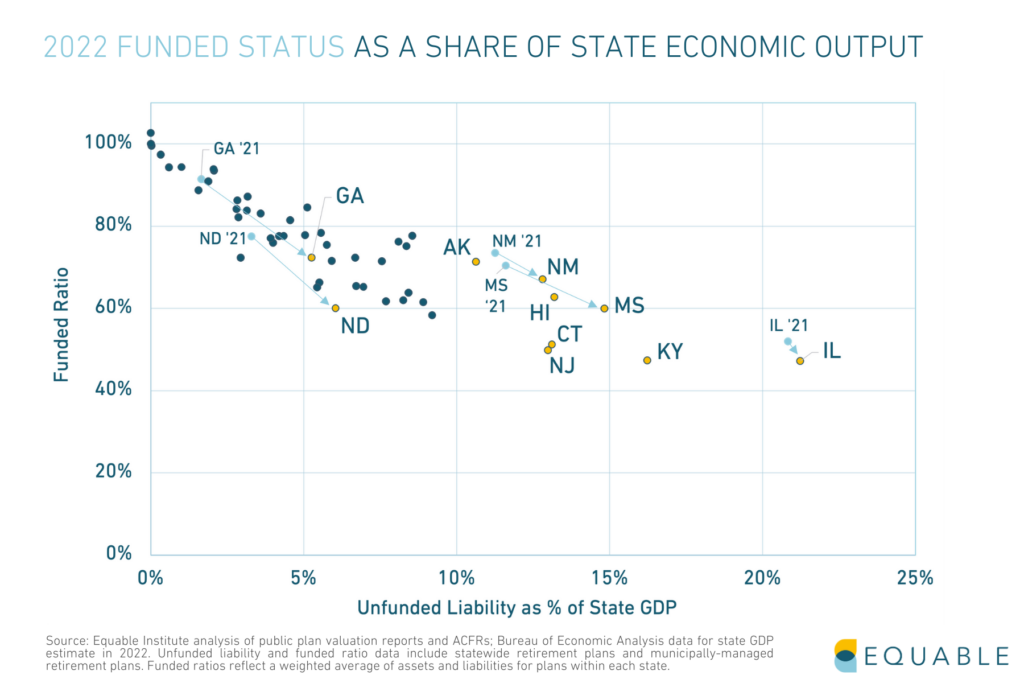

The funded ratio and pension funding shortfall are not the sole indicators of the health of a pension plan, however. Understanding the size of unfunded liabilities relative to the size of a state’s economy gives a sense of the scale of resources needed from a local tax base to improve pension funded status.

Prior to the pandemic, unfunded liabilities already accounted for a large share of many states’ GDPs. In our previous pension funding reports, we predicted the pandemic would lead to higher unfunded liability to GDP ratios. This is due to increasing funding shortfalls and economic contraction.

The chart below shows this for state totals and highlights how some states moved between 2021 and 2022.

How does pension debt impact states?

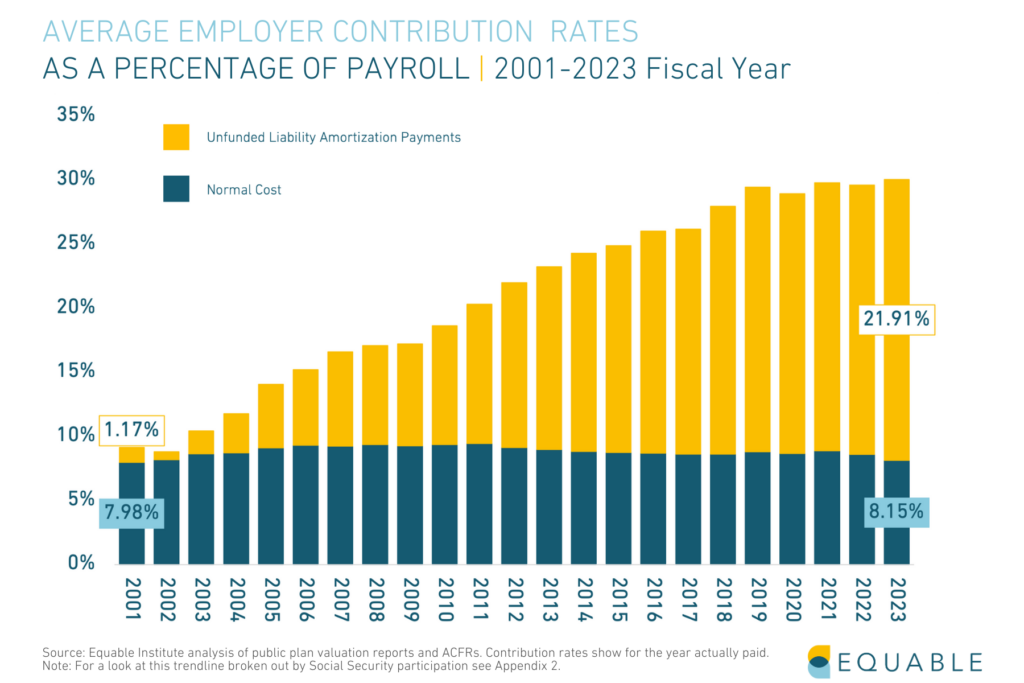

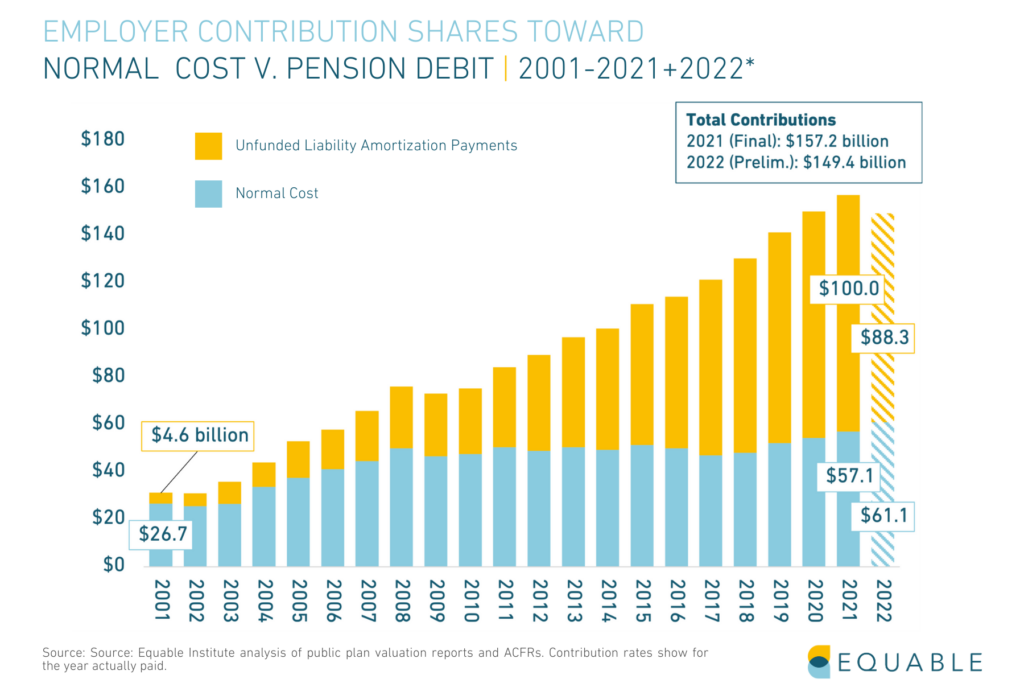

The growth of unfunded liabilities has made it significantly more expensive for states to provide public retirement benefits. In 2023, employer contribution rates reached an all-time high.

Government employer contributions have steadily increased over the past two decades, mostly because of increased payments to cover pension funding shortfalls (e.g., unfunded liability amortization payments).

Combined state and local employer contributions in 2001 were 9.15% of payroll. During the fiscal year ending 2023, employer contributions are 30.05% of payroll. In the chart above, you can see the normal cost of benefits has remained stable, while unfunded liability payments have grown exponentially.

On a dollar basis, Unfunded liability payments however have risen 2,089% during the same two-decade period from under $4.6 billion in 2001 (or $7.6 billion, adjusted for inflation) to over $100 billion annually in 2021.

At the same time, the value of public retirement benefits have been decreasing. Pension debt has meant that both states and employees are paying more for less when it comes to retirement benefits.

How will underfunded pension funds cover promised benefits for workers?

There are three strategies that states might take in seeking to ensure they can pay promised benefits to workers:

- Increase contributions into their pension funds,

- Pursue higher investment returns, or

- Reduce the value of benefits.

Cutting benefits is unconstitutional in almost every state, but some places have still cut or reduced benefits. They do this by cutting back on the inflation change of pension checks.

Pursuing higher investment returns has been the primary strategy of the past decade. While a few state pension plans were able to recover and some years produced good returns, overall investment returns have not been high enough for everyone to recover.

States will continue using this strategy, but it has high risks. And if it doesn’t succeed that leaves only the other two strategies.

The other key strategy is increasing contributions. Usually, when unfunded pension liabilities rise steadily over the years, employer contributions experience an uptick along with required employee paycheck deductions. Throwing more money into state pension funds will not help state funding shortfalls. State's must address the underlying issues to make any meaningful impact. That means pension debt and employee contributions may rise unabated until a change in policy mandates a reversal of problematic practices. Even a boon in investment returns has historically offered no guarantee that state and local governments will make debt payments in a timely fashion.

Click Here to Read the Full State of Pensions 2023 Report