In 2023 and beyond, public pensions in the United States are entering an era of new threats and more uncertainty than ever before.

The stagnant funding trend that followed the global financial crisis of 2008-09 has persisted for a decade and a half. This has left pension plans fragile and vulnerable to volatile market swings. 2021 and 2022 made this very clear. In the last year, political forces have subjected state and local pension funds to increasing pressure in how they invest assets. And — as if that weren’t a enough — there is another emerging threat to public pensions: valuation risk.

As 2019 came to a close, Covid-19 was a brewing threat to the world. The pandemic transformed many parts of society. It destabilized global financial markets and accelerated several demographic and labor market trends. All of these factors created a volatile climate for public pension plans. Four years later, when the 2023 fiscal year ended (for most pension funds), state and local retirement plans were back to where they started in 2019.

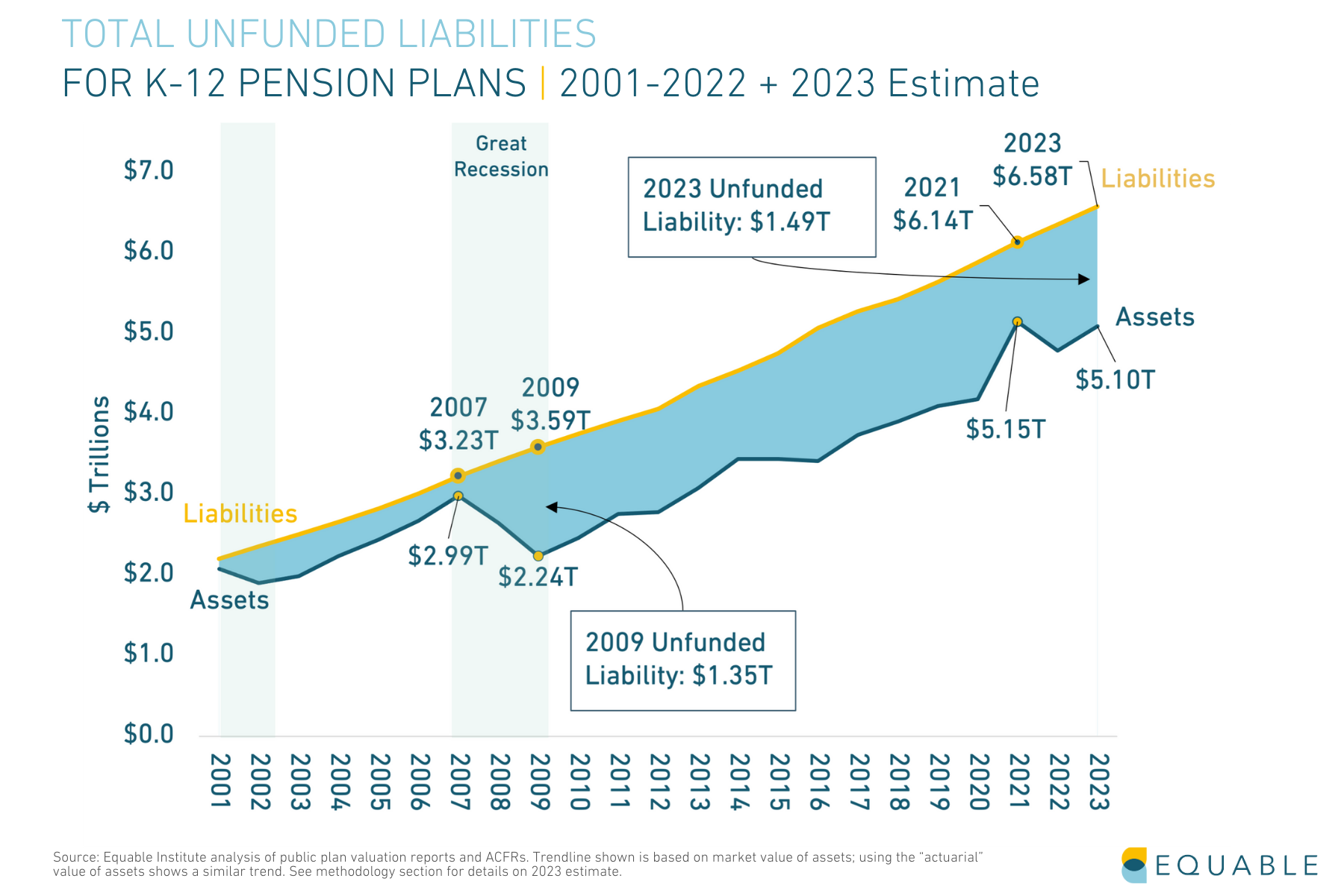

Unfortunately, that means public pensions are back to the stagnating trend line they were on before the pandemic. Public pensions had $1.54 trillion in unfunded liabilities in 2019. This inched up to $1.57 trillion in 2022. In 2023, Equable Institute estimates it will decline slightly to $1.49 trillion as of June 30, 2023. The funded ratio of those same pension plans has shuffled from 73% in 2019 to 75% in 2022, to an estimated 77% as of June 30, 2023.

This article features content from State of Pensions 2023

Read the Full Report

Certainly, public pension funds are in a better place in 2023 than they were before the pandemic in 2019. But, there isn’t much of a difference between a 2% increase or a 2% decrease in funded status relative to the status quo. The bottom line—the current state of public pension plans is stagnation and fragility.

Risk Addiction: Funded Status is Dependent on the Precision of Asset Valuations More Than Ever

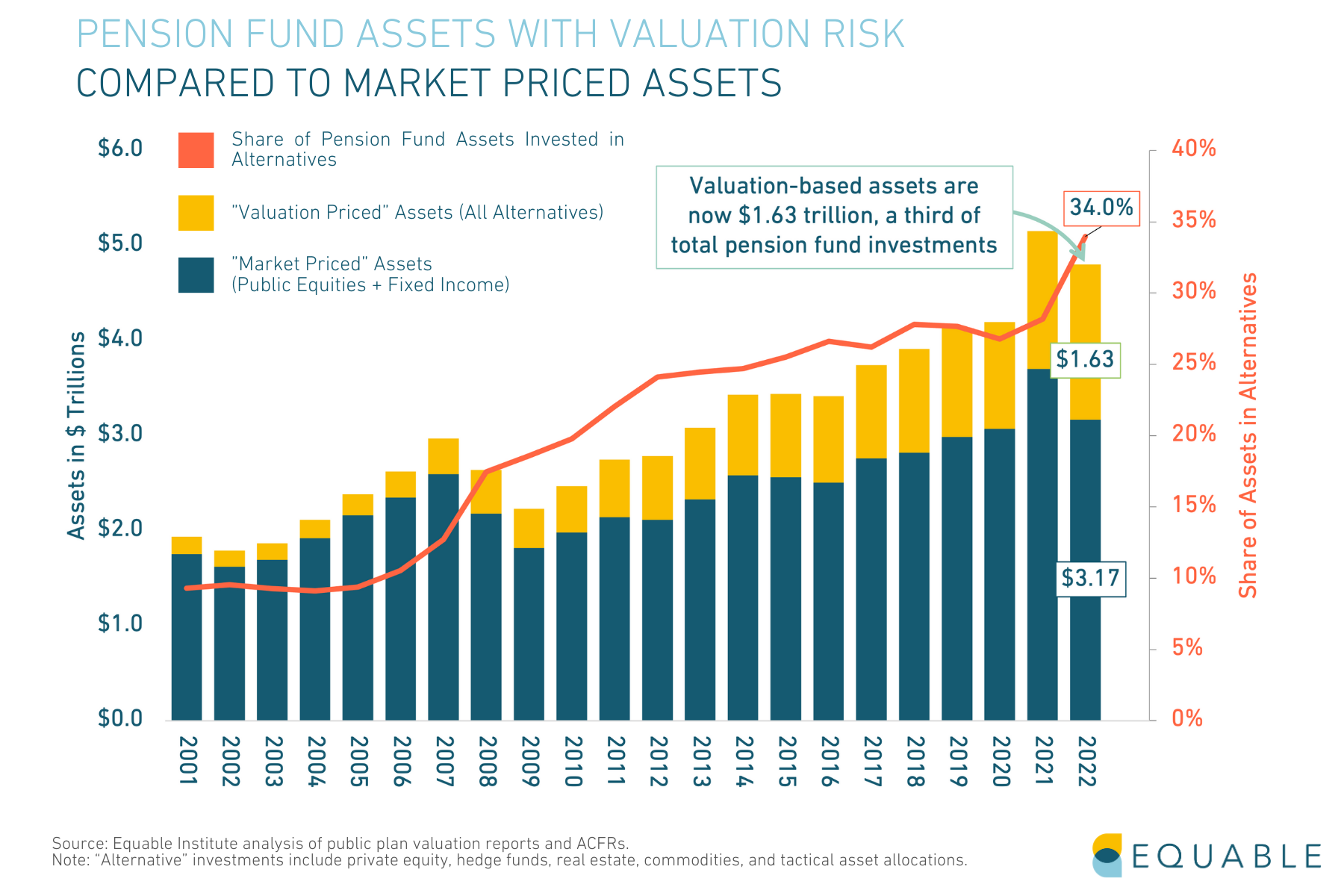

Before the financial crisis of 2008, pension funds reported they had around $3 trillion in asset. 88% ($2.6 trillion) of which was based on market prices. The other 12% ($390 billion) was based on fair market valuations. But at the end of 2022, the percent of public plan assets based on valuations had jumped to 34%. This represents $1.63 trillion in pension fund assets, as shown in the figure below.

This is an important trend that could have meaningful effect on contribution rates in the future. Contribution rates today are based reported assets. But, those assets are increasingly valuation based. If those valuations don’t align with the ultimate sale prices of the assets in a meaningful way, that could mean contributions paid in the past were insufficient.

While there has always been a risk that asset valuations might not comport with reality, it wasn’t as significant a problem when alternative investments were just 8%, 10%, or 12% of pension fund dollars. The gradual shift toward alternatives — and in particular, private equity — has created an emerging threat. State retirement systems and legislatures need to look at this trend closely.

The Shift into Private Equity and Alternatives

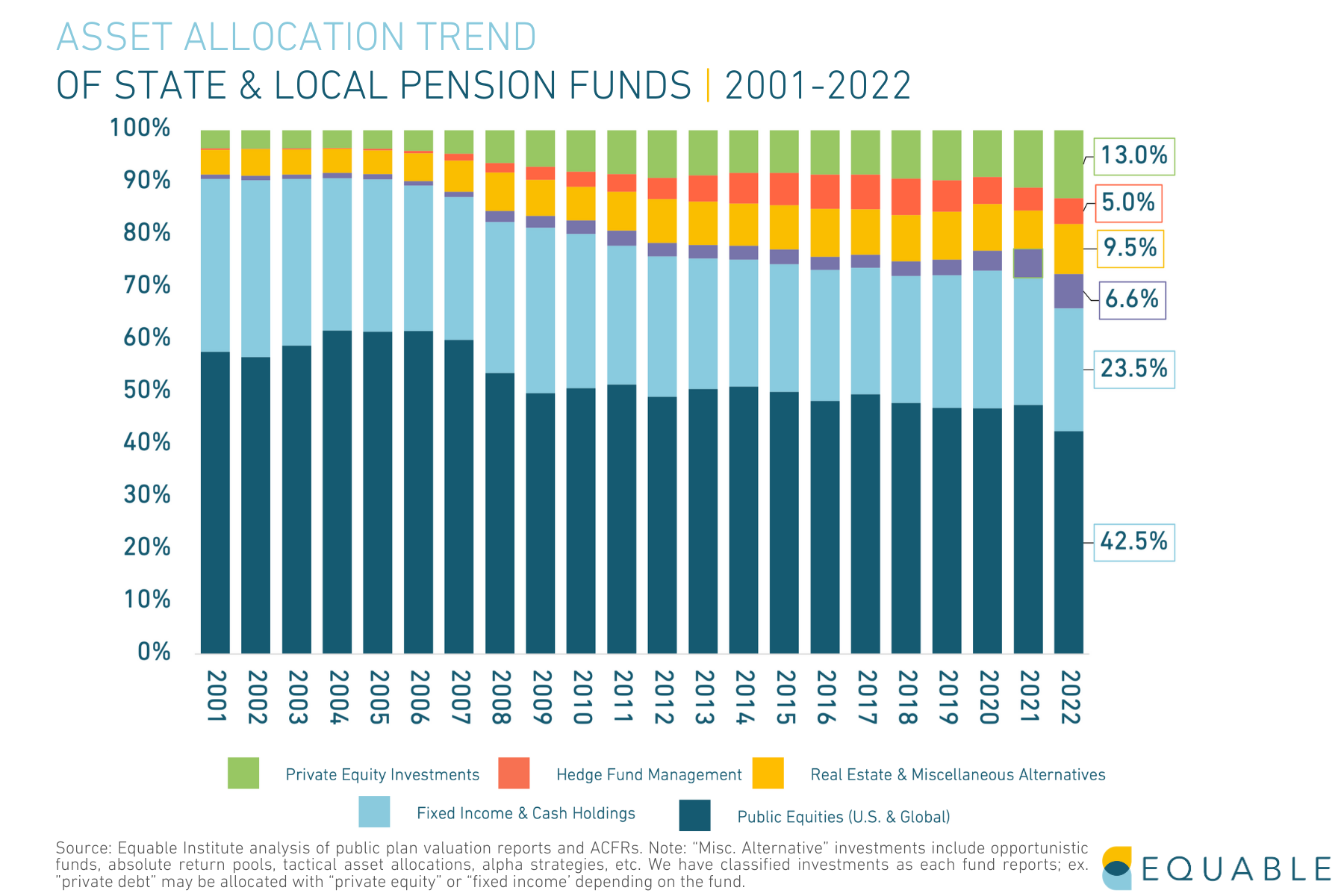

Over the past 15 years, pension fund assets have steadily shifted into alternatives. This includes private equity, real estate, hedge funds, commodities and other miscellaneous investments. While some of that money has come out of fixed income products, the shift has mainly been at the expense of publicly traded equities. The figure below illustrates this trend.

Coming into the 2023 fiscal year, 13% of pension fund assets were in private equity, 9.5% were in real estate investments, 5% were in hedge funds, and 6.6% were in commodities or other alternative investments. Every one of these was a historic high point. One factor driving the numbers in 2022 was the particularly low value of public equities. However, the major driver was the continuing trend of increasing dollars going into these asset classes.

Some of these investments have diversified pension fund portfolios to ensure there is less risk that a single market event will hit all assets under management—at least in theory. In practice, the integration of global markets during the late-20th and wary 21st centuries meant lower diversification returns than would have been earned in prior eras. Other portfolio shifts have added a mix of long-term investments that align with long-term liabilities.

However, most of these investments have added some combination of asset risk, illiquidity risk, and/or lack any meaningful transparency.

The Scale of Valuation Risk for Pension Funds

Some alternative investments are put into public markets. This might look like a hedge fund strategy that invests in public equities, or a total return fund that has a mix of public equities and fixed income products. (Public pension funds often don’t have great transparency in how they report or classify these investments. So, it can be hard to know exactly what specific strategies entail.)

However, the majority of alternative investments via private equity and real estate are priced using valuation models or when the assets are sold. For example, New York City Pension Funds reports that the value of its real estate and infrastructure investments as of April 30, 2023 is $22.4 billion. That figure is entirely dependent on property valuations, varying models for how to value real estate, and the timing of when asset managers decide to update the value of the investments. Maybe all of the valuations are sound, maybe not. We’ll only know once those assets are sold. In the meantime, New York City leaders need to understand that the contribution rates they are paying into the five pension funds for city employees are partially dependent on the quality of those valuations. There’s around $250 billion in assets managed by NYC Pension Funds. As much as $50 billion of those assets are based on valuations not market pricing.

CalSTRS recently announced that they are on the negative end of this phenomena. Until recently they’d reported the value of their commercial real estate was $52 billion. But, after taking account of reduced corporate property values, they’ve said they anticipate marking this down 20%. One the one hand, a $10-15 billion markdown isn’t a huge deal relative to a $300+ billion portfolio when it comes to solvency. On the other hand, an asset reduction of that scale can absolutely change the calculation of contribution rates for school districts in California.

It is Time for Public Plans to Report Valuation-Based Assets

Historically, asset values are reported by pension funds have been generally marked-to-market. There hasn’t been much reason to question the reported value of assets for a pension fund. Even if there were adjustments from year-to-year, they would be small shares of the portfolio.

More focus has been placed on the liability side, as pension funds can easily understate the value of their promised benefits with unrealistic actuarial assumptions. But now with such a large share of investment assets in alternatives, there is a growing risk that reported asset values are not going to hold up to future experience.

There was already a need for stakeholders and policymakers to take the reported value of liabilities with some grain of salt. Government Accounting Standards Board guidelines even require reporting a range for liabilities, not just a single number. The same level of skepticism is now warranted with respect to these assets.

Market Uncertainty: Contributions Rates are Dependent on the Mixed Signals of Long-Term Investment Performance

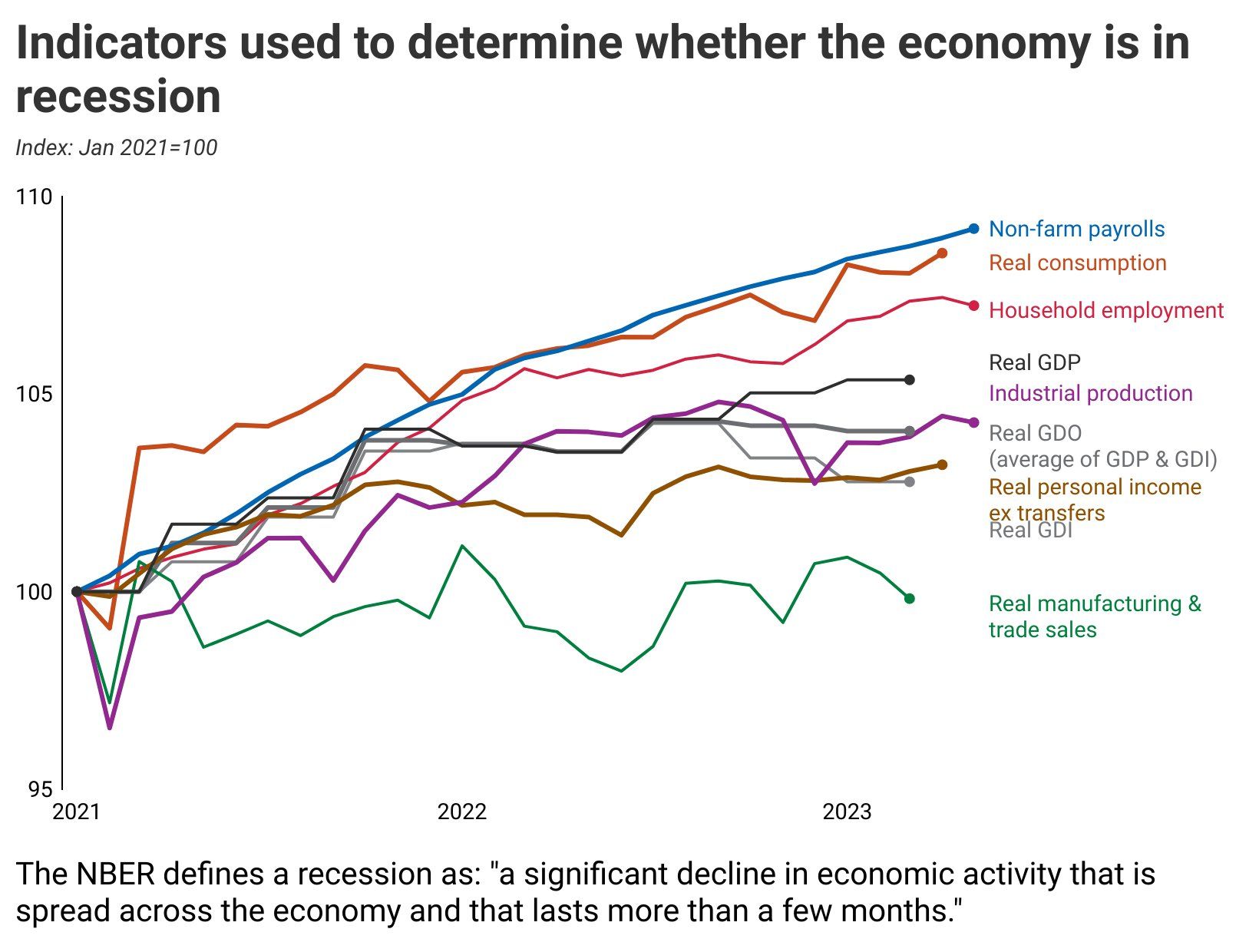

There have been widespread warnings about a recession and stock market crash over the last year. And while it's unclear whether or not there will technically be a recession, the effects of inflation have felt like a recession for many people. Plus, with interest rate pressure putting downward pressure on the economy, there is a significant possibility of lower tax revenues in the future. In short, there’s a lot of mixed signals.

Last year the S&P 500 and Dow Jones indices slipped into bear market territory. But, this year they are on the rise as they head into the second half of the 2023 calendar year. Consumer sentiments are moody, but none of economic indicators used to measure a recession have pointed toward one. For example, see the figure below (via economist Justin Wolfers):

Global markets are still highly integrated. (See all of the challenges created by supply chain breakdowns since the pandemic). However, in the U.S. and Europe there is increasing interest in industrial policy, skepticism of free trade, and increasing economic tension between China and the West. All of which could signal a change to global investing or even better returns to portfolio diversification.

Inflation is persisting, even if reduced as of June 2023.

Residential housing prices have cooled off a bit from 2021 and 2022 highs, but they still remain significantly elevated. But commercial real estate is on the path toward a crash that is likely to persist for some time as work-from-home policies continue. (See the CalSTRS canary in a coal mine warning about coming write downs for other pension fund real estate portfolios.)

Private equity deal making has slowed down, but private equity portfolio values have not necessarily declined.

There wasn't significant incentive to mark down private equity portfolios in 2022, even as public markets were falling. Technically, private and public markets don’t have to be correlated. And as interest rates were rising the era of easy and cheap money was ending, meaning private fund managers were facing an existential threat to their business models.

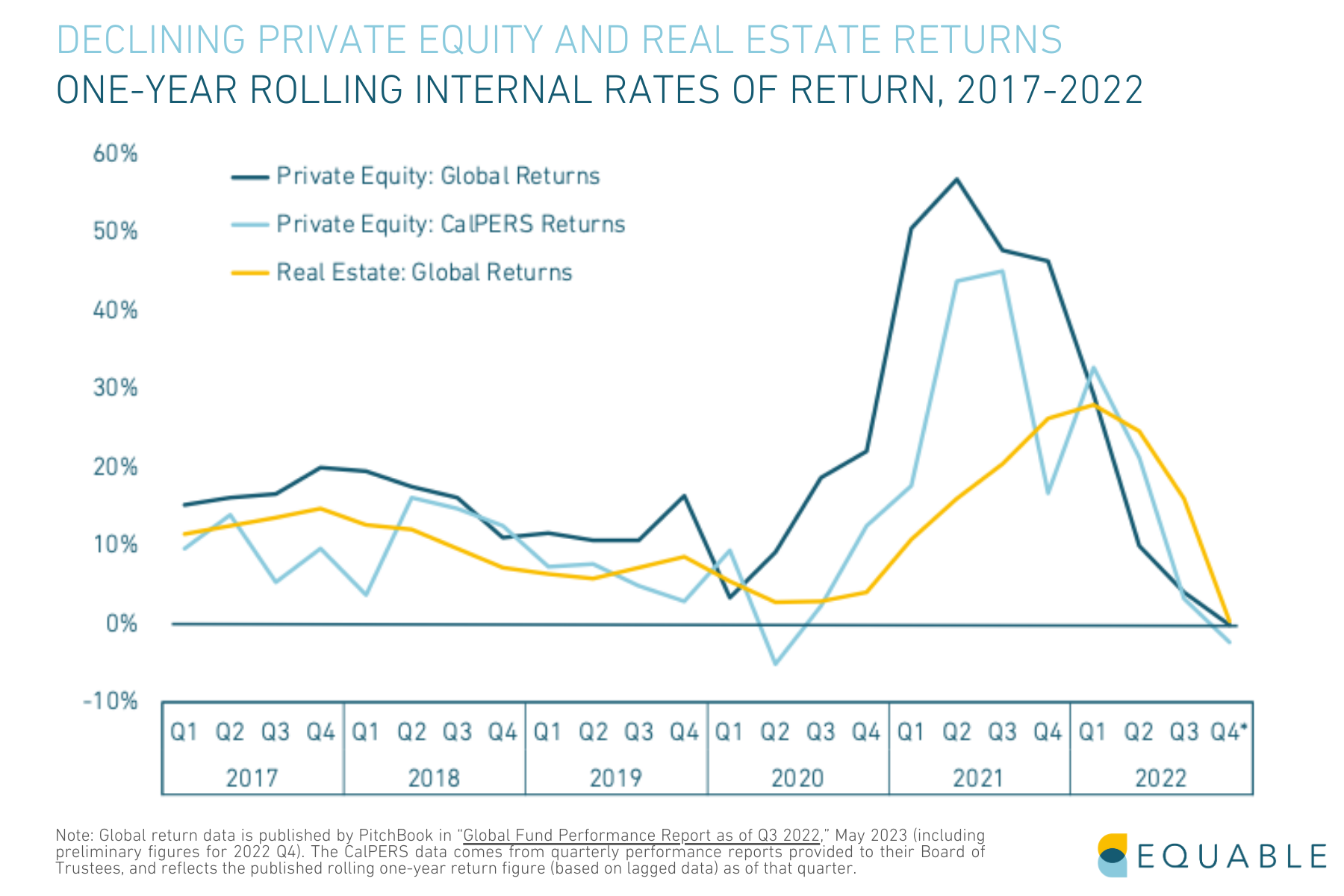

However, that doesn’t mean private equity valuations weren’t overstated. And we have seen the internal rates of return for global private equity drop, as shown in the figure below.

At the same time, lower internal rates of return do not directly translate to lower valued pension fund portfolios if updates to valuations are lagged or delayed until a fund’s cycle is complete.

So are markets trending up or down for pension fund investments? Should state governments be concerned about growing contribution rates while revenues are falling? The answers depend on who you ask and what data they are looking at.

Pension Politics: Political Pressures on Pension Funds are Increasing

There were more state legislative pension fund proposals for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues during the spring 2023 session than at any other point in the past.

Debates about the role of considering ESG factors in pension fund investments are nothing new. For years, pension fund stakeholders have debated ideas such as divesting from tobacco companies, banning investment in certain countries (like Sudan or Iran), or proactively investing pension fund money in green energy companies. However, ESG-specific debates have become a potent political issue amid larger political movements. This includes things like “stakeholder capitalism" and counter movements that are attempting to preserve the fossil fuel industry. For example, Texas passed a law restricting the state from doing business with financial companies who are deemed to be “boycotting” the oil and gas industry.

Most of the ESG and pension laws that were adopted in 2023 used similar language that refined rules around fiduciary responsibility. Such laws say that only financial factors (or pecuniary factors) should be considered when making pension fund investments. They also often emphasize that maximizing investment returns should be the goal of pension fund investing. However, these laws also go a step further and explicitly say that ESG factors should not be considered with respect to investing pension fund money. Based on the way that most states have written this clause in their statutes, the language doesn’t really influence how pension funds will operate. Prioritizing fiduciary duty inherently means not prioritizing other factors, like ESG. But, it does signal the intent of such laws is in opposition to ESG.

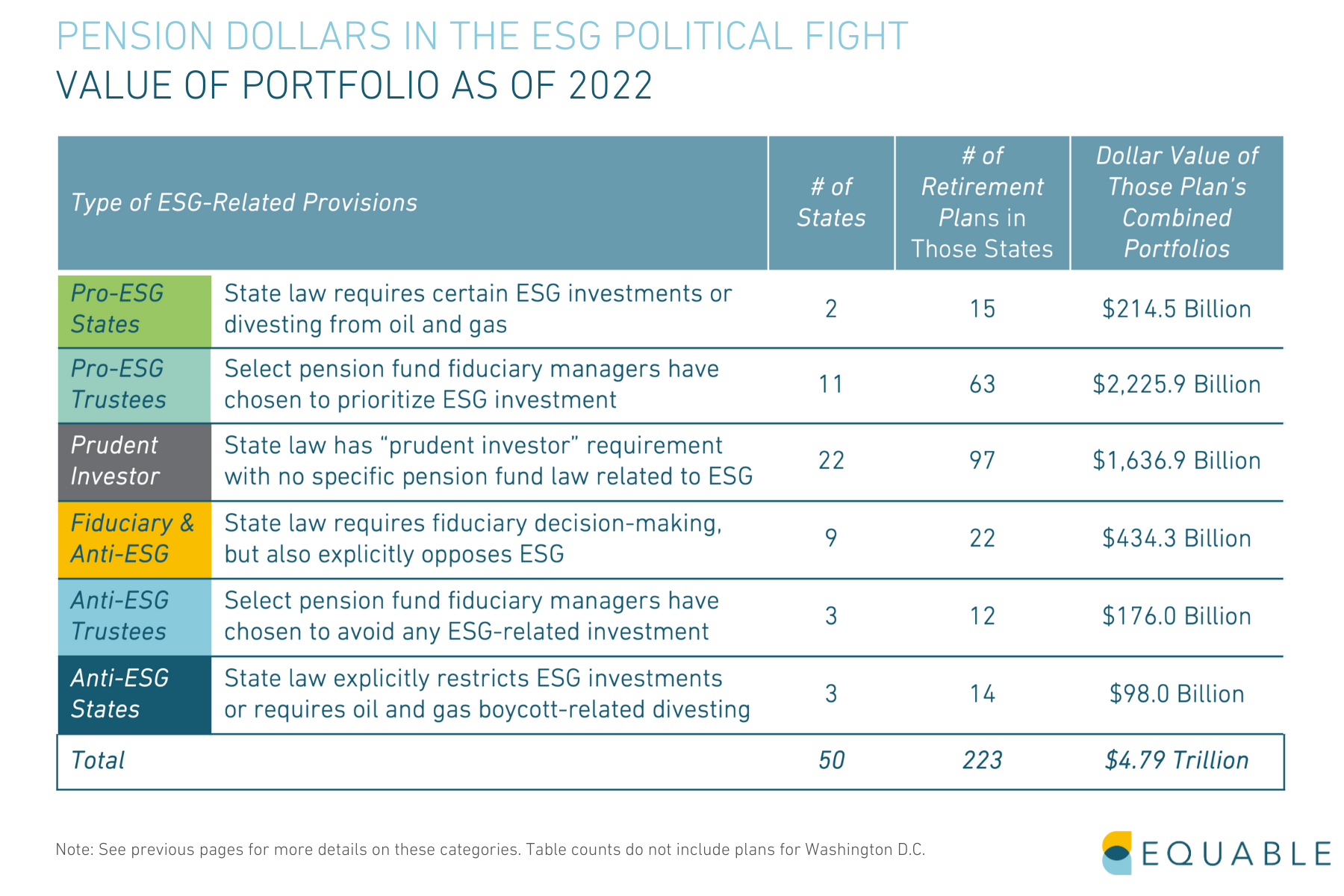

While there were nine states that adopted these kind of “fiduciary” or “pecuniary” prioritization laws that had an anti-ESG flair, the assets in those states ($434.3 billion) are less than 10% of the nationwide total, as shown in the table below. Notably, there are significantly more pension fund assets in states where ESG is treated favorably than in states that oppose ESG. This is largely driven by pro-ESG trustees in Illinois, New York, and California.

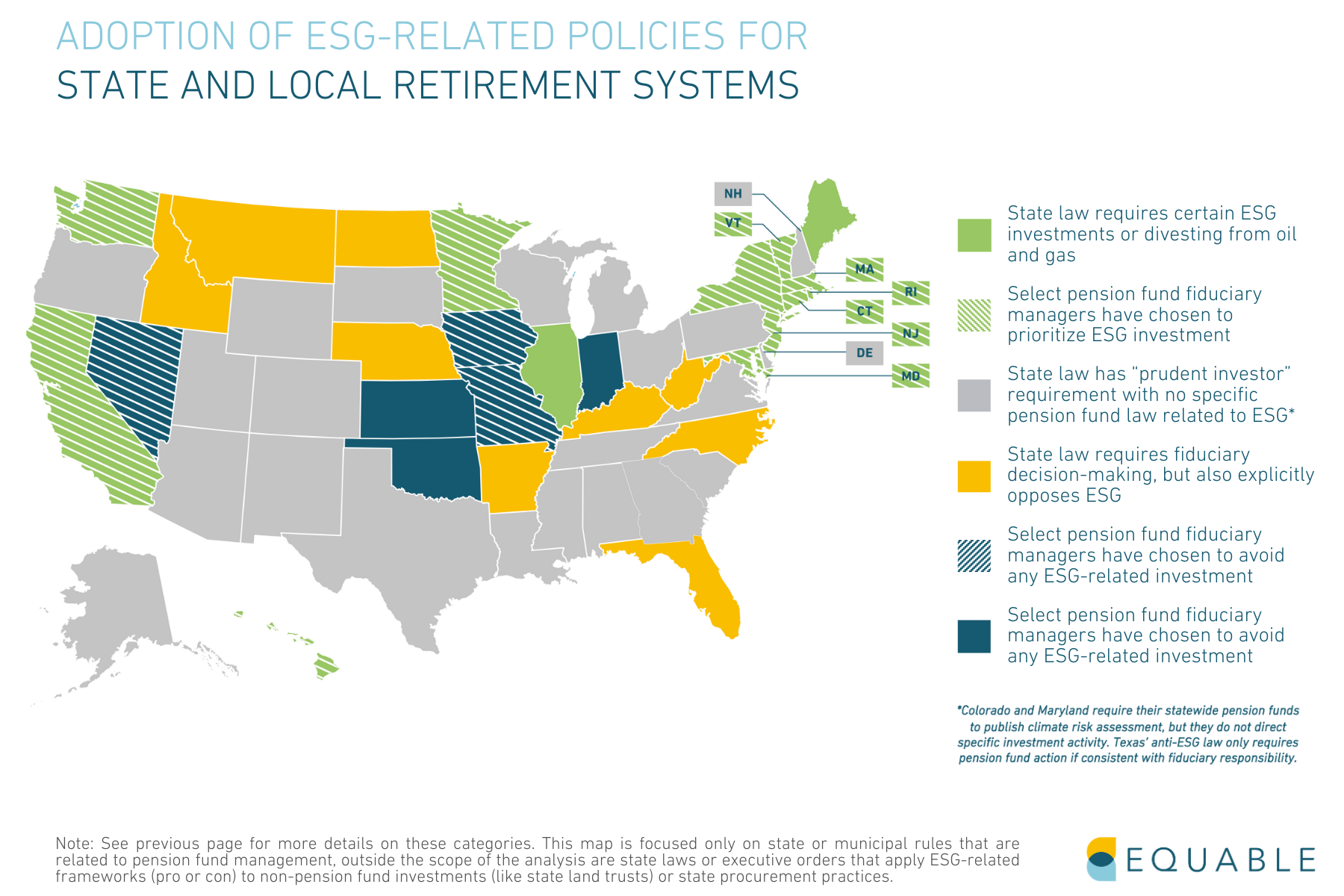

As of June 2023, only five states have laws on the books that are explicitly for or against ESG-factor investing. Most states taking action on ESG (for or against) have pension fund trustees acting on their own. The map below provides a snapshot of the state-by-state landscape.

Conclusion

During the fiscal year ending 2023, government employers will contribute an average of more than 30% of payroll to their defined benefit retirement plans. This is the highest contribution rate in history. Member contribution rates are also at historic highs, and a number of states have even made supplemental payments. This is the story of pensions in 2023.

But despite all of that, there is roughly $1.49 trillion in unfunded liabilities for the largest state and local pension plans, who are only 77.4% funded as of June 30, 2023.

In an increasingly politicized environment, the trustees of these pension funds face significant market uncertainties and high degrees of volatility. Many of those making investment decisions feel they have no choice but to take on more investment risk. This pressure is amplified by increasing negative cash flow that sometimes means benefit payments are consuming more than just contribution inflows.

All of this might be worth it if public employees uniformly had strong retirement security—but even benefit values are being threatened. The average COLA in 2022 (1.8%) was well below the actual rate of inflation. And Equable Institute has documented elsewhere that the value of new tiers of pension benefits introduced for teachers has declined 17% since 2005.

While there is no crisis on the horizon where waves of pension funds going insolvent or states facing overwhelming costs, there are warnings. Just look to the high costs of pension debt in Chicago, or the severe hidden education funding cuts in Pennsylvania. However, there is no question that the status quo for state retirement systems is unsustainable.