One of the first states to attempt improving the sustainability of its teacher pension plans was West Virginia in the 1990s. Unfortunately, the pioneers in this process bungled the process miserably. There are important lessons to learn from this experience about responsibly paying pension bills, ensuring that alternatives to pensions are providing a path to retirement security, and following through on promises made to individuals even if they are in a closed pension plan. Unfortunately, the West Virginia story is instead frequently cited as a cautionary tale to avoid working on improving pension system funding all together. And that version of analysis is incomplete.

The Problems West Virginia Was Trying to Solve

The 2018 teachers strike in West Virginia was not the first of its kind. Back in the spring of 1990, educators walked off the job across the state demanding better pay and improvement to the education system in West Virginia generally. At the same time, the West Virginia Teachers’ Retirement System (WVTRS) was roughly 10% funded with $3.5 billion in unfunded liabilities — a huge amount for 1990. The strike worked and teachers received a $1,000 across the board raise (around $1,900 in today’s dollars). The legislature also voted to create a new defined contribution retirement system for future teachers, given the struggles with the existing system.

The Complicated History of West Virginia’s Reforms

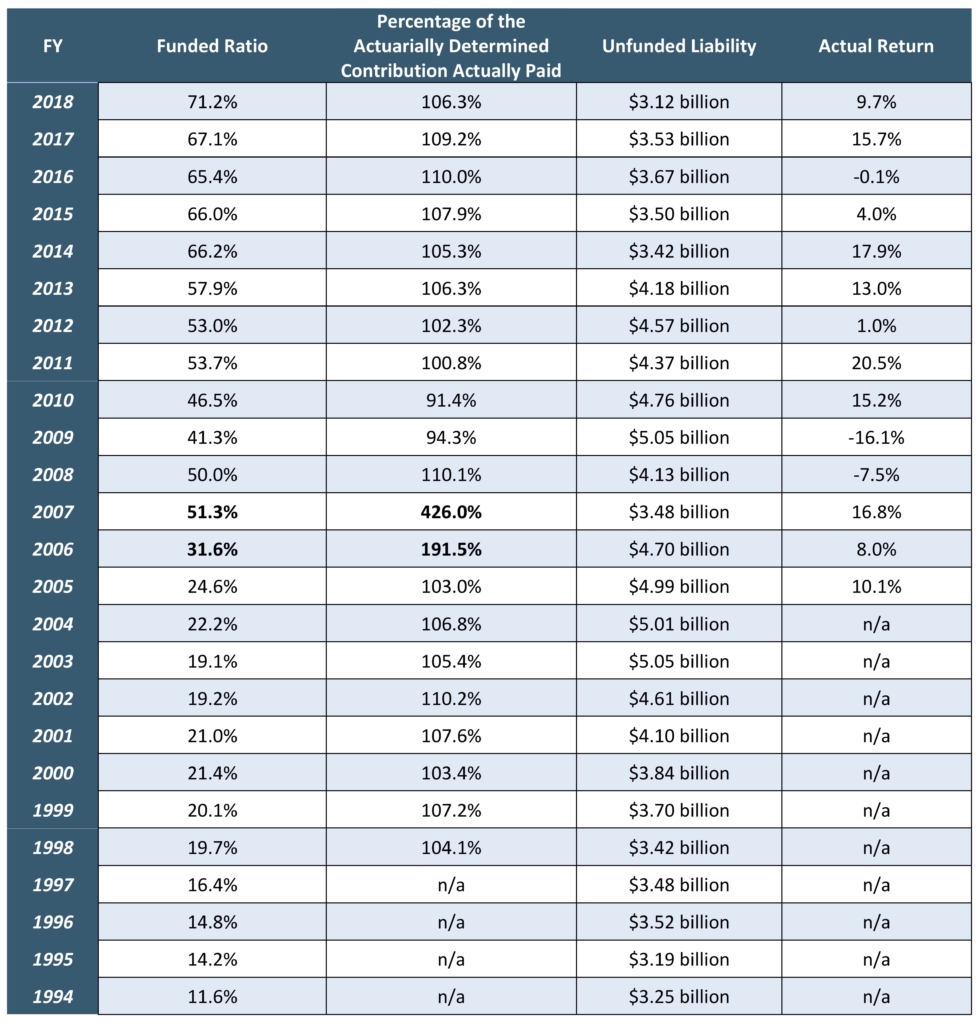

For most of the years after, the state legislature paid the actuarially determined contribution. But the funding policy generating that contribution rate wasn’t strong enough to drive the closed pension system quickly toward solvency. Between 1991 and 2004, the funded ratio of WVTRS had only improved from around 10% to 22%.

What happened next has been the subject of much controversy.

Here the perspective of those opposed to the reforms:

- After more than a decade, the legislative efforts from 1990 had not saved WVTRS. The pension system was still mired in unfunded liabilities.

- And to make matters worse, the closed retirement system was paying out more in benefits than it was bringing in with contributions, draining the fund.

- Meanwhile, the defined contribution plan was not helping teachers build adequate retirement savings. There weren’t sufficient required contributions or guardrails to help teachers effectively invest those contributions that were made.

But here is another perspective, critical of how reforms were implemented but not of the effort:

- After more than a decade, the legislative efforts from 1990 hadn’t saved WVTRS, but it was at least in a better position. The funded ratio was weak, but it was better than before. West Virginia was making the positive shift from a “pay-as-you-go” model in the 1980s (which led to the underfunding) to the more appropriate “pre-funding” model where normal cost pays for benefits accrued each year, and unfunded liability amortization payments are used to close any funding shortfall. They were just shifting too slowly.

- The state was paying out more in benefits than bringing in via contributions, but this shouldn’t have mattered if the underlying funding policy was focused making amortization payments in adequate, equal dollar amounts each year.

- Meanwhile, the defined contribution plan was definitely not offering enough in benefits to support retirement security. But this was in part the result of the poor design from the early 1990s (there was little known at the time about best practices for contributions and guardrails), and in part because the DC plan was employer focused (with long vesting periods) instead of being grounded in policies aiming to support retirement income for teachers. And neither of these failings are inherent flaws in DC plans

Funded Ratio History for WVTRS

Source: West Virginia Consolidated Retirement Board comprehensive annual financial reports, actuarial valuations, and GASB 68 reports.

Did Re-opening the Pension Plan Help WVTRS?

In 2005, West Virginia attempted to raise money with a bond issuance, but the measure failed. Instead, the legislature re-opened the pension plan to teachers. In the years since then, the funded ratio for WVTRS has improved, but the system has still struggled. In fact, in 2015, the state cut the value of benefits for future teachers and raised employee contribution rates in order to try again at improving the status quo.

Whether the re-opening of the pension plan itself has helped WVTRS is also a matter of some controversy.

Here is the perspective of those opposed to the reforms:

- Re-opening the pension plan created savings because the normal cost for pension benefits was only half of the employer contributions to the DC plan. These savings have helped the state improve the funded ratio.

- Pension benefits are more efficient than defined contribution benefits, and teachers are better off as a result.

However, here are two alternative perspectives:

First, re-opening the pension plan has not created budgetary savings that were used to improve the funded status of WVTRS. As I wrote in a case study for the Pension Integrity Project, there was a spike in the contributions paid to WVTRS in 2006 and 2007, the years after the system was re-opened. This was driven by using $807 million from a state settlement with tobacco companies, and the lump sum contributions pushed the WVTRS funded ratio up to around 50% by 2007. Since then, though, the funded ratio of WVTRS has not meaningfully improved, as shown in the nearby table.

The primary factor behind the improvement in WVTRS is not the re-opening of the retirement system but the responsible choice to add a lump sum of cash into the pension fund when the money was available — this could have been done even if the pension plan had remained closed.

Second, while the DC plan was providing inadequate benefits, the pension plan in West Virginia was similarly weak. Bellwether Education Partners did a comparative analysis of wealth accumulation for teachers in the pension fund, before and after the reform, as well as the intervening defined contribution (DC) plan. They found “that all of the plans were poorly constructed from the outset and fail to provide a significant retirement benefit to a majority of West Virginia’s educators.” In fact, their modeling shows that even the flawed DC plan was providing a more valuable retirement benefit to approximately 77 percent of West Virginia teachers:

- “For the first five years of service, the [West Virginia] DB plan generates a more valuable retirement benefit. However, due to vesting rules, teachers wouldn’t qualify for employer-provided benefits until completing their fifth year under the pension or their sixth year under the DC plan. But between teachers’ sixth and 33rd year of service, the DC plan produces greater retirement wealth. Given West Virginia’s teacher retention rates, that means the DC plan is a better option for more than three-quarters of the state’s educators.”

Taking the Right Lessons from West Virginia

There is nothing inherently good or bad about pension benefits. DC plans are not inherently a better or worse alternative to pensions. Efforts to reform retirement systems are not universally wise or foolish. The reality is that the management of public sector retirement benefits is a complex challenge. States should carefully examine their systems to consider what reforms can ensure high-quality retirement options to all educators in the plan, while also directly addressing the challenges they are trying to solve. Here are the key lessons to learn from West Virginia’s experience:

- West Virginia didn’t adequately fund its closed pension system, even though they were trying to do the fiscally difficult task of shifting to pre-fund retirement benefits. When closing a pension plan to new hires, the task of getting the debt paid off and sufficient funds into the system doesn’t go away, and it is hard work. West Virginia didn’t take advantage of the opportunity to get money into the closed system while new members were being added to an alternative retirement plan.

- West Virginia didn’t ensure its new DC plan was employee focused, with adequate policies to create a path to retirement security. While the DC plan reduced employer exposure to increased liabilities, the poor design doomed the retirement plan to future political failure.

- The correlation between the re-opening of the pension plan and its improved funded status is just a function of using the tobacco settlement money to pay down unfunded liabilities; there is no causal connection to re-opening the pension plan and improved funding.

- Re-opening the pension plan may have been appropriate to give an option to West Virginia teachers in retirement benefits, but ending enrollment in the DC plan nullified this potential value.

As the Bellwether study concludes, pension reform is not supposed to be an escape from the retirement obligations owed to current and retired teachers. Rather, “it is a change that allows state the opportunity to re-think how to provide tomorrow’s teachers with a more valuable benefit than they could have hoped for under existing plans.”

Taking the right lessons away from West Virginia can help other states avoid similar mistakes; failing to learn the right lessons could lead to costs for teachers and states alike.

Read More Here —

- Bellwether Education Partners Case Study Paper on West Virginia

- Pension Integrity Project Case Study Article of West Virginia