When it comes to public pension performance as of October 2022, the new CalPERS chief investment officer said it best when commenting on the investment losses this year for the nation’s largest pension fund: “This is a unique moment in the financial markets… our traditional diversification strategies were less effective than expected, as we saw both public equity and fixed income assets fall in tandem.” CalPERS lost 6.1% of their assets during the 2022 fiscal year, and they are not alone with their negative returns. As all major benchmarks indicated, state and local pension fund have widely been announcing that they lost money during the 2022 fiscal year that ran from last July through the end of this June. Among the largest 227 retirement systems in the United States, 128 have reported preliminary investment returns averaging -6% for their 2022 fiscal year.

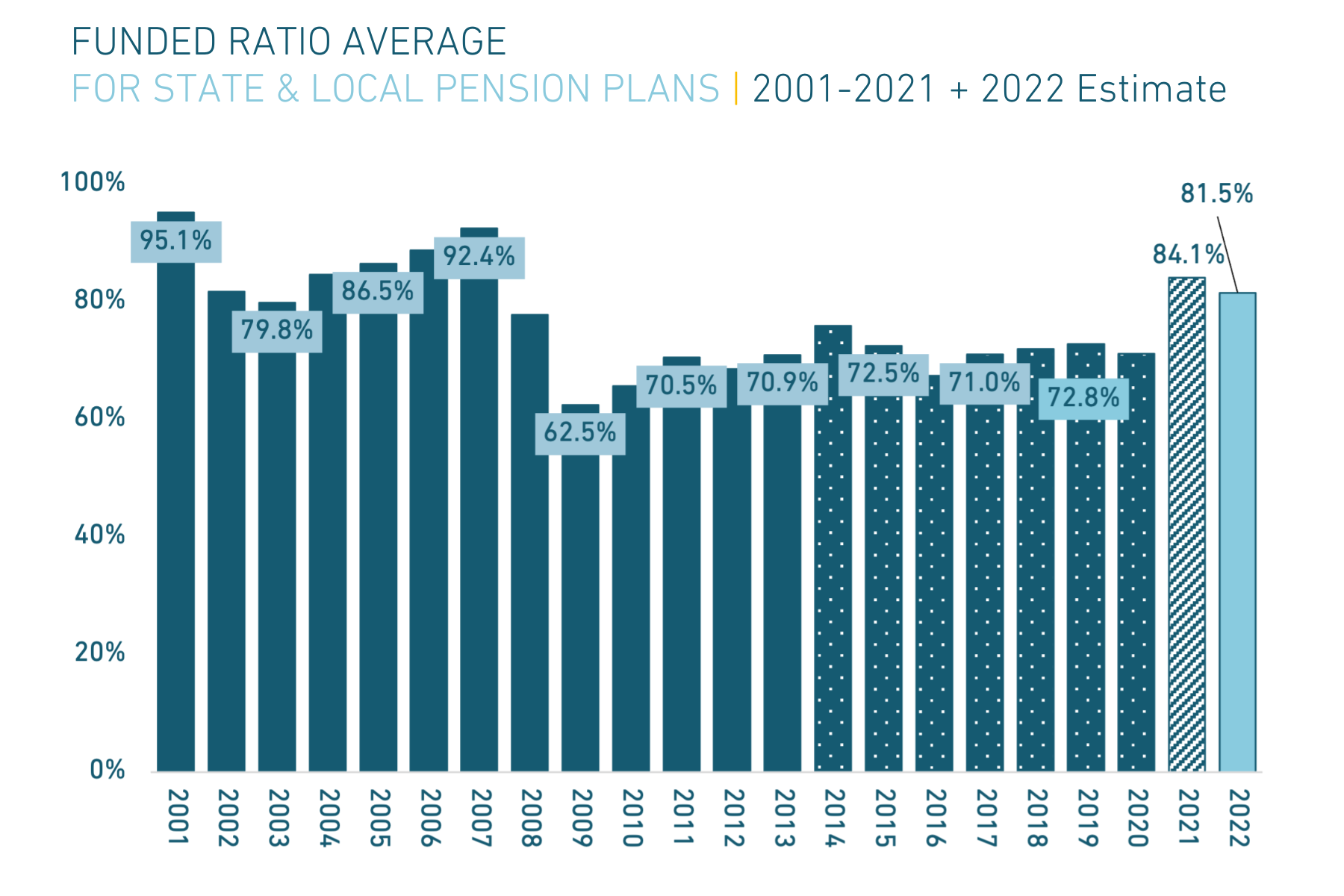

Based on the reported returns, the national level of state and local unfunded liabilities is $1.2 trillion, with a funded ratio of 81.5% — notably down from last year’s 84.1% funded ratio.

Visit the State of Pensions 2022 landing page for interactive charts and additional resources

Possible Good News for Public Pension Performance

There is some good news for pension performance, however. Maybe. The average preliminary returns for state and local pension funds is better than anticipated, based on data available in July of this year. Most pension funds lost money on their public stock holdings and even bonds in their portfolios, while real estate performance was strong. But while benchmarks for private equity return pointed to expected returns around -22.7%, the actual average private equity return among the 20 pension funds that have broken out their data is 24.8%.

The story of private equity returns in 2022 is complicated. But the short version of the story is that private equity investments earned so much in the last two quarters of 2021, that its more than balanced out the poor performance during the first six months of the 2022 calendar year. As a result, the “fiscal year” private equity returns for state and local pension plans look strong on paper.

This isn’t unalloyed good news though. If private capital markets do not improve over the coming months, then pension funds are looking at even worse returns for venture capital, buyout funds, and private debt in their 2023 fiscal year performance.

The good news might also be somewhat of an overstatement. Private market valuations do not get updated with same kind of pricing signals as public markets. The educated guesses and prior company transactions used to value companies in private equity fund portfolios may be overstating the value of pension fund private equity investments.

Funding Trends

The overall strong fiscal year performance for private equity has meant that 2022 is not a much of a loss as initially thought. As a result the decline in funded ratio isn’t as bad as it was in 2015 and 2018.

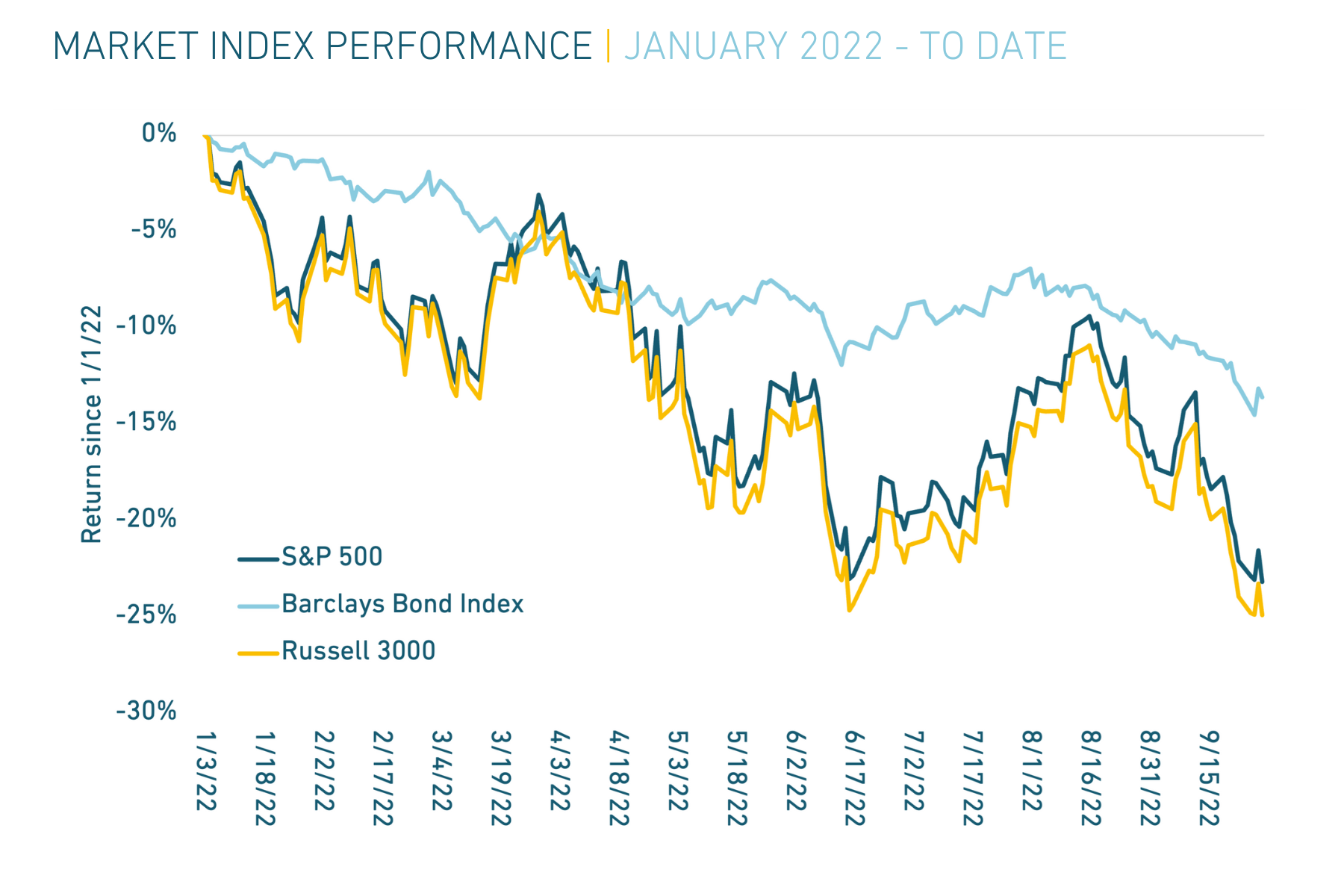

But to say something wasn’t as bad as something else implies that it was still pretty bad. While state and local pension funds often times have more elaborate investment portfolios than just stocks and bonds, the trend line for the major stock markets is telling.

Since January 2022, the S&P 500 is down 24.8% through September 30, 2022. The Russell 3000 is down 23.5%. And the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index is down 15.1%. In short, the market index trends indicate we are likely to see similar declines in public pension performance, when all plans are fully accounted for. All of these figures are shown in the below graphic.

Even with these losses in 2022, the overall trend for funded ratios since 2019 has been a gradual improvement on average. But if markets continue to decline that positive trend line will be threatened.

Contribution Rates On the Rise

Ultimately, the biggest reason why funded ratio trends are important is that they are a proxy for understanding where contribution rate trends are going. And while preliminary investment returns for 2022 are not as bad in September as they looked in July, asset levels still took a hit and were effectively unchanged from 2021. This means that at least one-fifth of the funded ratio improvement in 2021 has been wiped out.

All of which means that contribution rates are likely to increase in the coming years, despite last year’s gains.

The simple reality is that states, cities, and counties are not going to invest their way out of the $1.2 trillion funding shortfall that they have accumulated. If markets experienced an investment performance wave like 2021 for three to five straight years, then maybe things could be different. But 2021 brought forward investment returns from 2022 and 2023. And when investment performance is averaged out over the coming years state and local pension funds will be lucky if they have close to their assumed rates of return.

Which means more money is needed to pay down unfunded liabilities and keep them from getting more expensive over time.

What We are Watching for in 2023

Financial market performance is clearly one of the hottest topics facing public pension funds as this calendar year winds down and 2023 approaches. But there are other factors influencing pension funds that we are watching that have meaningful effects on the funded status of retirement systems and the benefits they payout:

- COLA rates paid out to retirees in the face of massive rates of inflation: the average cost-of-living adjustment paid out in 2022 has been 1.8%, much less than monthly changes in the consumer price index.

- Divestment and proxy fights are only getting more intense: there is a host of legislation expected in the spring of 2023 related to whether state pension funds should more proactively divest from fossil fuels… or divest from companies that are divesting from fossil fuels. There are fights over whether ESG should be a guiding principle for investment… or if pension funds should divest from money managers that prioritize ESG.

- The Russian invasion of Ukraine led to a quick wave of divestment demands, but action has been less than prompt: some states and pension funds simply have been writing their Russian investments down to zero (or near zero) and will aim to sell when they have an opportunity in the future; others have been more active in trying to dump their assets, but with limited success.

- Benchmarks used to measure state pension fund investment performance have long been suspiciously easy to beat.