If you’re like most public workers, you probably have to work five to seven years before you can qualify for any pension benefits — reaching this threshold is known as vesting.

Before vesting, no pension benefits have been guaranteed. If individuals enrolled in a pension plan leave employment before vesting, they are only entitled to receive back their own contributions.[1] The number of years required vest is the minimum necessary to qualify for claiming a future retirement benefit. Qualifications to claim a pension are usually a combination of years of service and age. For example, a common qualification threshold is 60 years old and at least 10 years of service. Another common qualification is “Rule of 90,” where the threshold to cross is any combination of age and years of service that add up to 90, such as 65 years old with 25 years of service.

Changing Vesting Periods

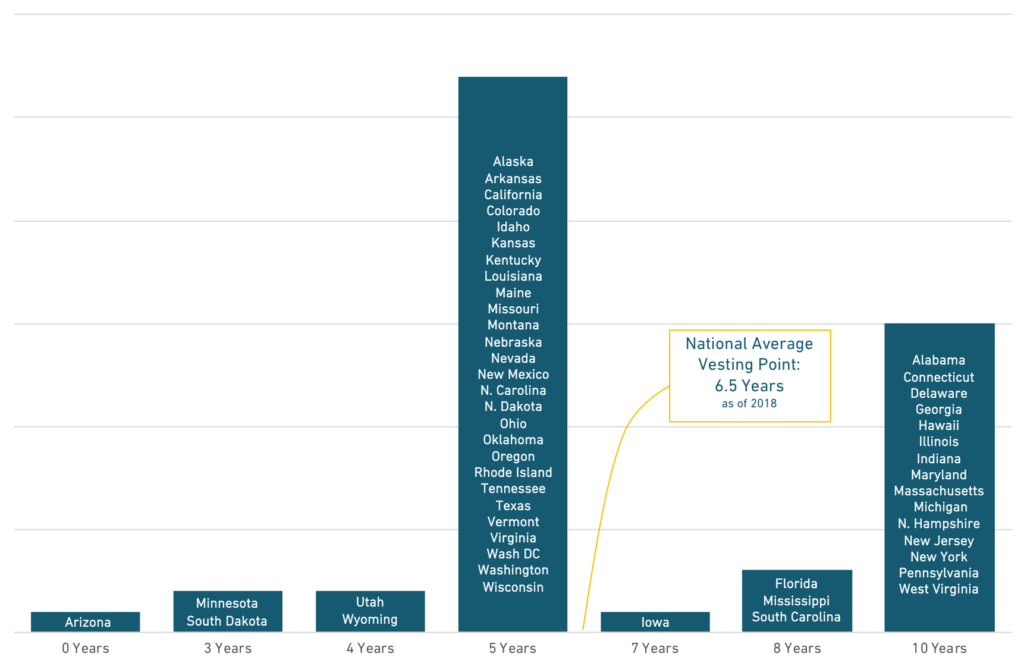

One way that states have changed public sector pension plans over the past few decades has been to increase the number of years required to vest. For example, in 2008 the average vesting period for pension plans covering teachers was 5.8 years. But over the past 10 years more than a dozen states have increased the pension vesting period. Today, the average vesting point is 6.5 years. As shown in the chart below, in 20 states teachers must now wait seven to 10 years to vest.

Source: Equable Institute and Lifting the Pension Fog

Some argue that longer vesting periods help retain teachers—though there isn’t strong research to back up this claim.[2] The reality is that longer vesting periods mean fewer teachers will receive pension benefits.

[1] The exception to this rule is South Dakota Retirement System, which will refund to a non-vested member upon leaving employment 100% of employee contributions and 75% of employer contributions on their behalf. SDRS is very rare in offering this kind of pension benefit.

[2] There is only limited empirical research on the effects of vesting periods. While it is possible that longer vesting periods might keep teachers who have spent four years in the workforce another year to reach a fifth year if vesting is at five years, teacher exit surveys suggest life events (such as having a child or a change in a spouse’s job), changes in job preferences, and school leadership are driving factors in causing teachers to leave their jobs — none of which will be influenced by a vesting period. See this report from Bellwether, 2018.

CURRENT MODULE

Pension Basics

How Pension Benefits Are Calculated How Does Vesting Work? Understanding The Pension Funding Formula What is the Assumed Rate of Return? What is Normal Cost? Unfunded Liabilities (aka Pension Debt) What are Actuarially Determined Contributions? Paying the Pension Bill Funded Status Pension Fund Governance Pension Myths: The Assumed Rate of Return Does Not Determine the Value of Benefits Pension Myths: The Funded Status of Pension Plans Does Not Depend on More Public EmployeesNEXT MODULE

View all Modules

View all Modules